Why Cultures Differentiate

Published 2025-12-12

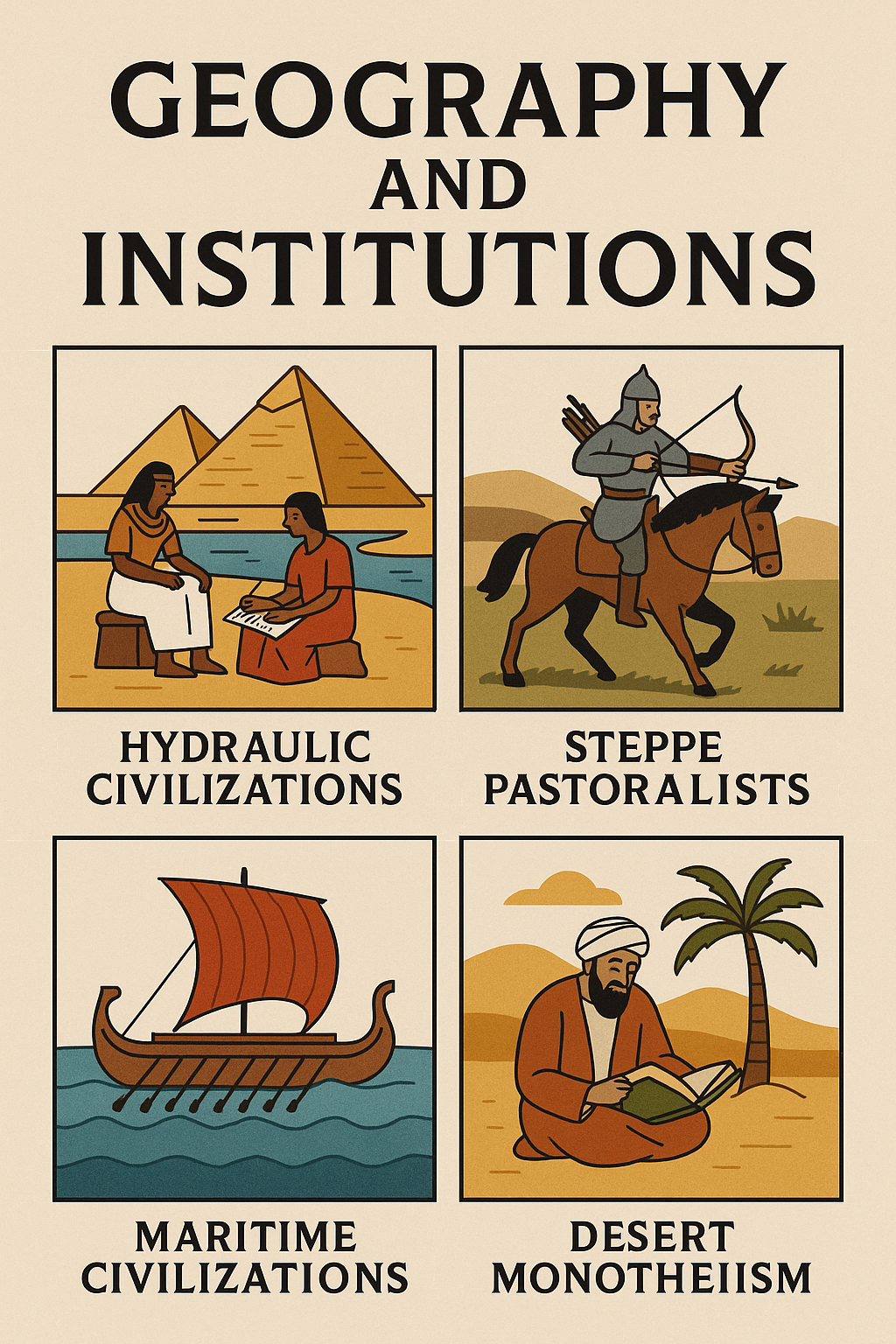

Geography creates a set of challenges for a people to manage. Each challenge requires a specific system to solve it. Each system requires a specific kind of people to uphold it. Centuries later, we see the results in different cultures.

Put another way, different coordination problems create different fitness landscapes for institutional personnel—the skills that get you promoted in a hydraulic bureaucracy differ fundamentally from those that advance you in a steppe confederacy.

Hydraulic Civilizations: Egypt & China

The coordination problem was managing annual floods—predicting timing, maintaining irrigation infrastructure, reallocating land boundaries after inundation, and storing surplus against bad years.

Selection criteria that emerged:

-

Literacy and numeracy: The ability to keep records of land boundaries, tax obligations, and grain stores. Egyptian scribes and Chinese literati were selected for mastering complex writing systems that took years to learn—a barrier that created a self-perpetuating administrative class.

-

Calendar/astronomical knowledge: Predicting the Nile’s flood or the Yellow River’s behavior required tracking celestial cycles. This elevated priest-astronomers in Egypt and calendar officials in China.

-

Examination systems: China eventually formalized this into the keju (imperial examination), which selected for classical textual mastery, calligraphy, and the ability to write structured policy essays. The exam selected for conformity to canonical interpretation as much as raw intelligence—a feature, not a bug, for bureaucratic coordination.

-

Patience and proceduralism: Hydraulic management rewards caution, documentation, and working through established channels. The institutional culture selected against bold risk-takers.

The Wittfogelian “hydraulic despotism” thesis is overstated, but the core observation holds: flood management really did create centralized bureaucracies with specific personnel profiles.

Steppe Pastoralists: Mongols, Türks, Comanche

The coordination problem was mobile: managing herd movements across vast territories, defending against raids while raiding others, and assembling coalitions for warfare that could dissolve after victory.

Selection criteria that emerged:

-

Martial meritocracy: Unlike settled aristocracies where birth determined command, steppe confederacies showed remarkable (if imperfect) selection for demonstrated military ability. Temüjin rose from captivity to become Chinggis Khan; Comanche war chiefs earned status through raids, not lineage.

-

Decimal organization loyalty: The Mongol tumen system (units of 10, 100, 1,000, 10,000) deliberately broke up tribal affiliations. Advancement went to those who demonstrated loyalty to the Khan over kin—selecting for a specific kind of transferable allegiance.

-

Logistical intelligence: Steppe warfare required reading terrain, managing horse remounts, coordinating multi-pronged attacks across hundreds of miles. Leaders were selected for spatial and logistical reasoning.

-

Personal charisma and gift-giving: Without fixed bureaucratic positions, leaders maintained followings through personal distribution of plunder. Selection favored those who could attract and hold nöker (companions) through generosity and perceived luck/suu (fortune/destiny).

The institutional “hardening” here was different—it produced law codes (the Mongol Yasa) and decimal military organization rather than civilian bureaucracy.

Maritime Civilizations: Greeks, Phoenicians, Venetians

The coordination problem was managing sea trade: financing risky voyages, building and crewing ships, maintaining networks across multiple ports, and defending against piracy.

Selection criteria:

-

Commercial risk assessment: Maritime trade created selection for those who could evaluate ventures, diversify cargoes, and manage partnerships. Athenian liturgies (where wealthy citizens financed warships) selected for both wealth and civic reputation.

-

Rowing-class citizenship: Athenian democracy expanded precisely because trireme warfare required mass participation. The thetes (poorest class) who rowed gained political voice—the coordination problem of naval warfare selected for inclusive institutions in ways that cavalry-based warfare did not.

-

Networked trust: Phoenician and later Venetian systems selected for family trading networks that could maintain relationships across vast distances. Personnel rose through demonstrated trustworthiness in remote transactions.

-

Rhetorical skill: Greek city-states, coordinating as trading equals rather than hydraulic subjects, selected leaders through persuasion in assemblies. The agora produced selection for public speaking that would be useless (or dangerous) in a pharaonic court.

Desert Monotheism: Islam (and its Arabian context)

The coordination problems were multiple: managing scarce water and pasture, organizing long-distance caravan trade, and arbitrating disputes among tribal groups without a central state.

Selection criteria:

-

Legal-jurisprudential expertise: Islam’s institutional innovation was the ulema—scholars whose authority derived from mastery of fiqh (jurisprudence). Selection was through chains of scholarly transmission (isnad), creating a decentralized credentialing system that could function across vast territories without central bureaucracy.

-

Memorization and oral mastery: The hafiz (one who memorizes the Quran) held special status. Scholarly authority required memorizing vast hadith collections with their chains of transmission. This selected for a specific cognitive profile.

-

Merchant-scholar overlap: Muhammad was a merchant; early Islam spread along trade routes. The institutional culture respected commercial success as compatible with (not opposed to) religious authority—unlike some Christian traditions.

-

Arbitration ability: Pre-Islamic Arabia selected for hakam (arbitrators) who could resolve disputes between groups lacking common political authority. This carried into Islamic qadi (judge) selection.

Contested Corridors: The Levant and Ancient Israel

The coordination problem was survival at the crossroads of empires—maintaining identity and cohesion while repeatedly conquered by Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Persia, Greece, Rome.

Selection criteria:

-

Textual/legal expertise: When you can’t rely on political sovereignty, identity maintenance shifts to portable institutions—texts, laws, practices. This created intense selection for scribes, interpreters, and those who could maintain tradition across displacement. The sofer (scribe) and later the rabbi emerged as central figures.

-

Diaspora network management: Selection favored those who could maintain community cohesion without territorial sovereignty—a very different skill than administering a flood plain.

-

Prophetic/interpretive flexibility: The tradition selected for figures who could reinterpret founding narratives to explain current catastrophe (exile, conquest) as meaningful rather than random—selection for theodicy-production.

-

Endogamy enforcement: Without territory, boundary-maintenance shifted to marriage rules, dietary laws, and practice distinctiveness. Institutional roles emerged around enforcing these boundaries.

The meta-pattern: each environment’s coordination problem created a fitness landscape where certain cognitive profiles, social skills, and personality traits were differentially rewarded. Over generations, these selection pressures produced recognizable institutional “types”—the Chinese literatus, the steppe warlord, the Greek rhetor, the Islamic jurist, the rabbinic scholar—each optimized for their particular coordination niche.