Burnout is a Modern Invention

Published 2025-12-15I argue that burnout is a symptom of today’s moralizing of labor. Something new, not experienced in prior centuries.

...No one forces her to live this way. Her employer doesn’t chain her to her desk. If anything, HR sends emails about “work-life balance” and “mental health resources.” The coercion, such as it is, comes from inside. She can’t not check email because she would feel anxious not checking. She can’t rest without guilt because rest feels like failure. She can’t conceive of a life that isn’t structured around productivity because—and this is the crux—she doesn’t know what else there would be…

I. The Pre-Capitalist World: Markets Without Capitalism

The crucial distinction: markets, money, trade, even wage labor are ancient. Capitalism is not. What’s missing in earlier arrangements is the ethos—the moral valorization of endless accumulation and productive activity as ends in themselves.

The Greek Citizen

The Athenian gentleman’s goal was schole—leisure. (Our word “school” descends from it: learning is what you do when freed from necessity.) Work, ponos, was burden, what slaves and foreigners did. The free citizen’s life was politics, athletics, symposia, philosophy.

Aristotle distinguishes oikonomia (household management, aimed at sufficiency) from chrematistics (money-making without limit). The first is natural; the second is dangerous, a disordering of means and ends. A man who pursues wealth beyond what supports the good life has confused the tool for the purpose.

Even wealthy traders aspired to convert commercial success into land and leisure—to stop working. Accumulation was a means to exit from accumulation.

The Roman Senator

Romans organized life around the polarity of otium (leisure) and negotium (business). Note the construction: nec-otium, not-leisure. Business is defined as the absence of the thing worth having.

Cicero, in De Officiis, ranks occupations. Trade is sordid if petty, tolerable if large-scale, but respectable only if the merchant retires to a country estate. The end point is always withdrawal into dignified leisure—reading, writing, cultivating one’s land and mind. The Roman ideal was the villa, not the firm.

Even during the commercial efflorescence of the late Republic and Principate, no one argued that accumulation was virtuous in itself. The rich man who kept working when he could afford otium was pitiable or vulgar.

The Medieval Craftsman

Here the moral constraints become explicit theology. The doctrine of the just price held that goods should be sold for what they’re worth—enough to sustain the craftsman in his station, no more. Profit beyond sufficiency was avarice, a mortal sin.

Usury was prohibited. Money should not breed money. Investment for return—the heart of capitalism—was conceptually blocked.

Work was organized through guilds that set hours, quality standards, and prices. Competition was constrained. The point was to maintain each member in his accustomed place, not to enable some to outcompete others into ruin.

And the calendar! Medieval Europe had somewhere between 100 and 150 feast days annually—saints’ days, holy days, parish festivals. The peasant and craftsman worked hard during working time, but working time was not most of time. The Church mandated rest.

The goal was sufficiency within your station. The monk sought God; the knight sought honor; the peasant sought survival and festival. None sought infinite accumulation. The concept barely existed.

What these share: commerce, hierarchy, often exploitation. But nowhere do we find the proposition that productive work is a moral duty, that time is money, that idleness is sinful, that one should systematically reinvest rather than consume, that there is no “enough.”

The pre-capitalist subject worked when they had to. When the necessity lifted, they stopped.

II. The Calvinist Mutation

Weber’s thesis is often vulgarized into “Protestants liked money.” The actual argument is stranger and more psychological.

Luther’s contribution is the concept of Beruf—calling or vocation. Medieval Catholicism reserved “calling” for religious life. The monk had a vocation; the butcher just had a job. Luther democratized the concept: even mundane work serves God. The butcher glorifies his Creator through excellent butchery.

This elevates work but doesn’t yet explain accumulation. The Lutheran could work diligently and then rest, satisfied in having served.

Calvin adds predestination—and with it, anxiety. God has already chosen the elect. You cannot earn salvation; it’s decided. But how do you know if you’re among the saved? You can’t, not with certainty. But maybe there are signs. And what might signal divine favor? Prosperity, success in your calling, the evident blessing of God upon your works.

Now the psychological trap closes. If prosperity signals election, then the failure to prosper suggests... what? You can never work hard enough to be certain. Every success demands another, as fresh evidence. Every hour of idleness risks being seen—by God, by the community, by yourself—as evidence of reprobation.

Worse: the Calvinist inherits the ascetic suspicion of consumption. You must work hard AND not enjoy the fruits frivolously. So you accumulate, reinvest, accumulate again. Systematic thrift in service of no earthly enjoyment.

This produces something genuinely new: a subject who feels morally compelled to endless productive activity, who experiences rest as sinful, who accumulates without a stopping point because the stopping point would invite doubt about election.

Secularization

The brilliant horror is that the religious framework can drop away while the habit remains. Benjamin Franklin—Weber’s exemplary figure—moralizes productivity in purely secular terms. “Time is money.” “Sloth makes all things difficult.” The theological skeleton has been removed, but the capitalist body keeps moving.

Now laziness is no longer a sin against God but against... what? Yourself. Your potential. Society. The imperative has been internalized so thoroughly that it needs no external justification.

III. The Achievement Subject Today

A portrait:

She wakes at 5:47 AM, the time calculated by her sleep-tracking app to catch the end of a REM cycle. This isn’t rest surrendered reluctantly to the alarm; it’s an optimized input.

Her morning routine is engineered. Cold shower for cortisol. Meditation for focus. Journaling for clarity. Coffee, timed to catch the cortisol dip ninety minutes after waking. Each practice serves output.

Work follows, but the category is porous. Is responding to Slack at 7 AM work? What about the podcast on productivity she listens to while making breakfast? The line between labor and self-improvement has dissolved because both are optimization.

She exercises after work—but “exercise” is wrong. She trains. She has a program, progressive overload, tracked metrics. The body is another system to be improved. Rest days are programmed for recovery, which is to say: rest is an input to future output.

Evening: she reads, but the books are either professional development or “personal growth.” She might meet friends, but there’s a whisper of networking in it, or at least the guilty sense that she’s not using the time productively. Leisure is hard to enter without a justifying frame. This is how I recharge. Rest becomes instrumental, which means it isn’t rest.

She is tired most of the time. Not the good tiredness after effort but a chronic, gray exhaustion that she attributes to insufficient optimization. If she were doing it right—sleeping better, meditating more, working smarter—she wouldn’t be this tired. The exhaustion is treated as personal failure, not systemic symptom.

When she burns out, she will frame it as a personal breakdown. She didn’t take care of herself. She didn’t set boundaries. She wasn’t resilient enough. The word is important: the modern worker is expected to be resilient, which is to say, to absorb systemic dysfunction into her own body without complaint and to emerge still functioning.

No one forces her to live this way. Her employer doesn’t chain her to her desk. If anything, HR sends emails about “work-life balance” and “mental health resources.” The coercion, such as it is, comes from inside. She can’t not check email because she would feel anxious not checking. She can’t rest without guilt because rest feels like failure. She can’t conceive of a life that isn’t structured around productivity because—and this is the crux—she doesn’t know what else there would be.

What is she working toward? Career advancement, financial security, the ability to... eventually... do what, exactly? Retire? And do what in retirement? The picture is vague. There is no telos, no vision of the good life that isn’t “more options.” The hamster wheel spins, and stepping off isn’t even imaginable as an option.

IV. The Contrast

Place them side by side: the Roman senator and the modern knowledge worker.

Both work. But the Roman’s work is for something. He manages his estates, engages in politics, perhaps trades—so that he can secure the material basis for otium. The goal is the villa, the library, the long afternoons of reading and conversation, the cultivation of friendship and wisdom. Work is a means to a life beyond work. At some point, there is enough.

The modern worker’s work is also ostensibly for something—security, advancement, the ability to “live well.” But what does living well mean? Mostly: the capacity for more optimization. Better apartment, better gym, better vacations (which will be photographed and shared, a kind of labor). The end point recedes as you approach it. There is never enough because “enough” has been replaced by “more.”

The Roman would look at the modern Sunday—the productive workout, the meal-prepped lunches, the email check, the self-improvement reading—and ask: why are you still working? You’re free. Where is your otium?

The modern would look at the Roman’s afternoon—wine, poetry, conversation without agenda, unstructured hours—and feel a kind of vertigo. But what are you accomplishing? Isn’t this lazy? What about your goals?

They would not understand each other because they have different anthropologies. The Roman assumes that humans have a natural end (contemplation, political life, leisure with friends) and that work serves this end. The modern assumes that humans are bundles of potential to be maximized and that life consists of endless optimization toward no particular terminus.

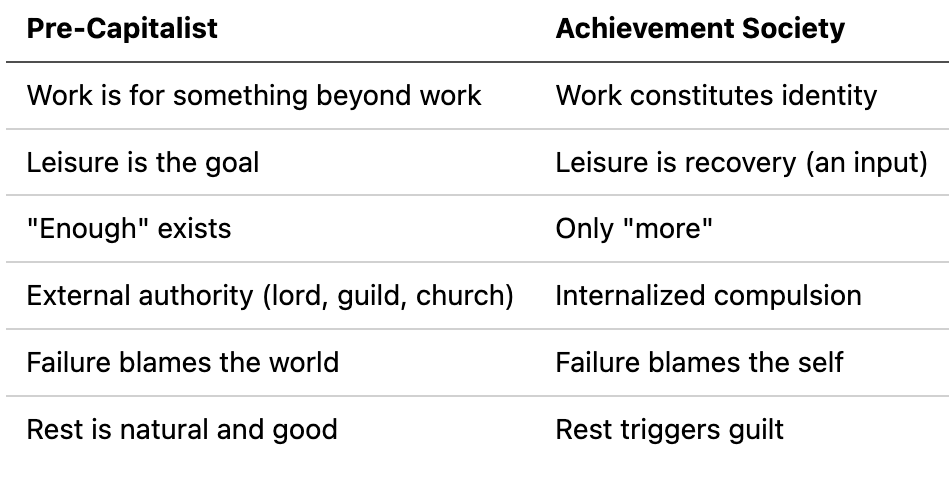

What has changed:

The trap:

The modern subject is, in the juridical sense, free. No one commands her. The coercion has been internalized so thoroughly that it registers as desire. She wants to optimize. She wants to achieve. And this wanting has been so completely colonized by the logic of productivity that she cannot even articulate an alternative.

Against what would she rebel? There’s no lord to overthrow, no chain to break. Only the voice in her head saying you could be doing more, and that voice sounds like her own.

This is Han’s achievement-subject, and this is why your friends don’t feel unfree. The bars are inside the cell. The warden is the inmate. Freedom and domination have become indistinguishable—which is not a paradox but the terminal stage of a very long historical process.