Know Thyself: Confucian, Buddhist, Hindu

Published 2025-12-15

-

Pt 1: Greek vs Christian

-

Pt 2: Buddhist vs Confucian vs Hindu

-

Pt 4: No Self

“The one who sees that suffering arises and passes away has seen all of reality.” — Samyutta Nikaya 12.15

Introduction: Beyond the Greek-Christian Binary

The previous essay traced a fundamental shift in Western self-understanding: from the Greek model of self-knowledge as rational audit to the Christian model of self-knowledge as excavating hidden desire. But this binary, however illuminating, remains parochial. Three great Asian traditions—Buddhism, Confucianism, and Hinduism—offer psychologies that differ not only from the Christian model but from the Greek as well, and from each other.

Each tradition asks different questions: Buddhism asks whether there is a self to know at all. Confucianism asks whether the self can be known apart from its relationships. Hinduism asks whether the self we think we know is the real self, or merely a case of mistaken identity.

These are not merely philosophical positions but lived practices—meditation techniques, ritual systems, contemplative disciplines—that shape different ways of inhabiting human consciousness. By examining them, we continue the therapeutic project of the previous essay: showing that our habits of self-relation are not necessities but possibilities among others.

Part I: Buddhism—The Self That Isn’t There

The Doctrine of No-Self

Buddhism begins with a radical claim: the self you are trying to know does not exist. The doctrine of anattā (Pali) or anātman (Sanskrit)—”no-self”—is not a denial that experience happens, but a denial that there is a substantial, enduring entity behind experience.

The Buddha in the Pali Canon systematically dismantles the self by analyzing it into components:

“Form is not self. For if form were self, then form would not lead to affliction, and one could say of form: ‘Let my form be thus, let my form not be thus.’ But because form is not self, form leads to affliction, and one cannot say of form: ‘Let my form be thus, let my form not be thus.’”

— Anattalakkhana Sutta, Samyutta Nikaya 22.59 (trans. Bodhi)

This argument is then repeated for feeling (vedanā), perception (saññā), mental formations (sankhārā), and consciousness (viññāna)—the five aggregates (khandhas) that constitute what we call a person. None of them is self because none of them is under our control in the way a self should be.

The point is not metaphysical speculation but practical liberation. If you search for a self and cannot find one, you stop clinging to a fiction:

“When a monk sees that the five aggregates are impermanent, suffering, and not-self, he becomes disenchanted. Through disenchantment, he becomes dispassionate. Through dispassion, he is liberated.”

— Khandha-samyutta, Samyutta Nikaya 22.59

What Replaces Introspection?

If there is no self to excavate, what does Buddhist practice actually examine? The answer is: phenomena as they arise and pass away. The meditator watches experience without identifying with it:

“In the seen there will be merely the seen; in the heard, merely the heard; in the sensed, merely the sensed; in the cognized, merely the cognized. When for you there is merely the seen in the seen... then you will not be ‘with that.’ When you are not ‘with that,’ you will not be ‘in that.’ When you are not ‘in that,’ you will be neither here nor beyond nor between the two. This itself is the end of suffering.”

— Bāhiya Sutta, Udana 1.10 (trans. Thanissaro)

This is extraordinarily precise and extraordinarily strange. The instruction is not to know what you see but to see it as merely seen—without adding the layer of selfhood, without constructing a “me” who is having the experience.

The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta—the foundational text on mindfulness—prescribes systematic observation of body, feelings, mind-states, and mental objects. But the mode of observation is distinctive:

“A monk abides contemplating the body as body, ardent, fully aware, and mindful, having put away covetousness and grief for the world... He abides contemplating feelings as feelings... mind as mind... mental objects as mental objects.”

— Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya 10 (trans. Bodhi)

The repetition—”body as body,” “feelings as feelings”—signals that the meditator sees phenomena as what they are, without adding interpretation, without constructing narratives, without asking “what does this mean about me?” There is observation without an observer who owns the observation.

The Difference from Christian Confession

The contrast with Christian examination of conscience is stark. The Christian asks: “What did I want? What was my hidden motive? What does this desire reveal about my sinfulness?” The Buddhist asks: “What is arising right now? Is it pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral? Is it wholesome or unwholesome? Is it passing away?”

Christian practice assumes a self that must be purified. Buddhist practice assumes a self that must be seen through. The Christian digs into the self to find truth. The Buddhist watches the self dissolve upon examination.

The Zen tradition makes this explicit with the kōan—a question designed to short-circuit the self’s attempts to understand itself:

“What was your original face before your parents were born?”

— Traditional Zen kōan

This is not a question to be answered by introspection. It is a question that, properly held, destroys the questioner. There is no “original face” to find because there is no substantial self that precedes experience. The kōan’s function is not to produce self-knowledge but to produce the collapse of the self-knowing project.

Suffering as the Problem, Not Sin

The Greek worried about ignorance. The Christian worried about sin. The Buddhist worries about dukkha—suffering, unsatisfactoriness, the pervasive friction of existence.

“Birth is suffering, aging is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering; union with what is displeasing is suffering; separation from what is pleasing is suffering; not to get what one wants is suffering; in brief, the five aggregates subject to clinging are suffering.”

— Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, Samyutta Nikaya 56.11 (trans. Bodhi)

Suffering arises from craving (taṇhā) and clinging (upādāna)—and specifically from clinging to the idea of a self. The therapeutic move is not to purify the self but to release the grip:

“When one sees, ‘This is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self,’ one is released.”

— Anattalakkhana Sutta

There is no hidden truth to excavate because the “self” that would contain hidden truth is itself the problem. Liberation comes not from self-knowledge but from the cessation of the self-project altogether.

Part II: Confucianism—The Relational Self

Self as Role-Performance

Where Buddhism dissolves the self into phenomena, Confucianism dissolves it into relationships. There is no “self” apart from one’s roles as child, parent, sibling, friend, subject, ruler. Self-cultivation is not introspection but the perfection of relational performance.

The Analects never ask what Confucius really wanted. They ask how he acted:

“In his village, Confucius was modest and appeared not to be able to speak. In the ancestral temple and at court, he spoke eloquently, though cautiously.”

— Analects 10.1 (trans. Slingerland)

The text catalogues his behavior in extraordinary detail: how he dressed for different occasions, how he stood, how he ate, how he mourned. The assumption is that these external performances are the self—that there is no hidden Confucius behind the ritual behavior, or rather, that whatever is hidden matters less than what is enacted.

Ritual as Self-Cultivation

The Confucian path to self-knowledge passes through lǐ—ritual propriety. By performing rituals correctly, you become the person the rituals shape:

“Yan Hui asked about humaneness. The Master said, ‘To subdue oneself and return to ritual—this is humaneness. If for one day you could subdue yourself and return to ritual, the whole world would return to humaneness.’”

— Analects 12.1

“Subdue yourself and return to ritual” (kèjǐ fùlǐ)—the formula suggests that the self must be overcome through ritual, not excavated through introspection. The problem is not hidden desire but unrefined behavior. The solution is not confession but practice.

Xunzi, the great systematizer of Confucian thought, is explicit about the transformative power of ritual:

“Human nature is evil; its goodness is the result of conscious effort. Now, the nature of man is such that he is born with a love of profit... He is born with feelings of envy and hate... Therefore, man must be transformed by teacher and ritual before he will become upright.”

— Xunzi, “Human Nature is Evil” (trans. Watson)

Notice the model: humans are shaped by external practices, not by internal discoveries. You become good not by finding your true self but by submitting to ritual discipline until the rituals become second nature.

Learning, Not Excavation

The characteristic Confucian activity is xué—learning, study. The Analects opens with it:

“The Master said: ‘To learn and at due times to repeat what one has learned, is that not a pleasure?’”

— Analects 1.1

Learning here does not mean acquiring information but forming character. You study the classics, you practice the rites, you observe exemplary models, you refine your conduct through feedback. The self emerges through this process—it is not waiting to be discovered.

Mencius, who argued (against Xunzi) that human nature is good, still locates self-cultivation in the expansion of innate tendencies through practice, not in excavating hidden depths:

“The feeling of commiseration is the beginning of humaneness; the feeling of shame and dislike is the beginning of righteousness; the feeling of modesty and yielding is the beginning of propriety; the feeling of right and wrong is the beginning of wisdom. Human beings have these four beginnings just as they have four limbs.”

— Mencius 2A:6 (trans. Van Norden)

These “four beginnings” are sprouts (duān)—incipient tendencies that must be cultivated, not hidden truths to be uncovered. The agricultural metaphor is important: you grow a self, you do not dig one up.

The Relational Field

Where the Christian confession is dyadic (soul and God, penitent and priest), Confucian self-cultivation is embedded in a web of relationships. The “five relationships” (wǔlún) define the moral field: ruler-subject, parent-child, husband-wife, elder-younger, friend-friend.

“Between father and son there should be affection; between ruler and minister there should be righteousness; between husband and wife there should be attention to their separate functions; between old and young there should be proper order; between friends there should be faithfulness.”

— Mencius 3A:4 (citing the ancient sage-king Shun)

Self-knowledge in this context means knowing your roles and how to enact them properly. The question is not “what do I really want?” but “what does this relationship require?” The self is not a hidden interior but a nexus of obligations.

The Absence of Confession

There is no Confucian confession. When you err, you do not verbally expose your hidden motives to an authority figure. You recognize your failure, feel shame (chǐ), and correct your behavior:

“When you see a worthy person, think of becoming their equal; when you see an unworthy person, examine yourself inwardly.”

— Analects 4.17

“Examine yourself inwardly” (nèi zì xǐng)—but what you examine is whether you have the same faults, not what hidden desires produced them. The examination issues in behavioral correction, not verbal confession.

The Confucian sage does not need to confess because he has nothing to hide—his interior has been shaped by ritual until it matches his exterior:

“At seventy, I could follow what my heart desired without transgressing what was right.”

— Analects 2.4 (Confucius describing his own development)

This is not the absence of desire but the education of desire. The sage’s heart has been trained until it wants what is right. There is no gap between hidden motive and visible action—not because he has confessed the gap away, but because practice has closed it.

Part III: Hinduism—The Self Behind the Self

Ātman: The Witness

Hinduism presents perhaps the most complex psychology because it contains multiple schools with different views. But a central strand—developed in the Upanishads and systematized in Advaita Vedānta—posits not that there is no self, but that there is a deeper self behind the self we think we know.

The ordinary self—the psychological self with desires, memories, and personality—is not the true self. Behind it stands ātman: pure consciousness, the witness of all experience, identical with Brahman, ultimate reality.

“This Self is not this, not this (neti neti). It is ungraspable, for it is not grasped. It is indestructible, for it is not destroyed. It is unattached, for it does not attach itself. It is unbound; it does not tremble; it is not injured.”

— Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad 4.2.4 (trans. Olivelle)

The via negativa—neti neti, “not this, not this”—indicates that ātman cannot be known as an object. Everything you can point to, everything you can describe, everything you can observe—that is not it. The self is the observer, never the observed.

The Chariot Metaphor

The Kaṭha Upanishad offers a famous image of the psychological architecture:

“Know the Self as the lord of the chariot, and the body as the chariot. Know the intellect (buddhi) as the charioteer, and the mind (manas) as the reins. The senses, they say, are the horses, and the sense objects are the paths they range over. The wise call the Self—when united with body, senses, and mind—the enjoyer.”

— Kaṭha Upanishad 1.3.3-4 (trans. Olivelle)

Notice the layering: body, senses, mind, intellect—and behind all of these, the Self as “lord of the chariot,” the one for whom the whole apparatus operates but who is not identical with any of its parts.

This creates a distinctive practice: not excavating desires (Christian) or dissolving the self (Buddhist) or perfecting relational performance (Confucian), but discriminating between self and not-self, between the witness and what is witnessed.

Ignorance, Not Sin

The fundamental problem in Vedānta is avidyā—ignorance, specifically ignorance of one’s true nature. You are already Brahman; you simply do not know it:

“That which is the subtle essence—in that all that exists has its self. That is the True. That is the Self. And you are that (tat tvam asi), Śvetaketu.”

— Chāndogya Upanishad 6.8.7 (trans. Olivelle)

Tat tvam asi—”you are that.” The statement is not an aspiration but a declaration of fact. You do not need to become Brahman; you need to realize you already are. The problem is not that you have sinned and need purification (Christian) or that you are clinging and need release (Buddhist) or that you are unrefined and need cultivation (Confucian). The problem is that you are confused about what you are.

Śaṅkara, the great Advaita philosopher, uses the metaphor of the rope and the snake:

“Just as a man in the dark mistakes a rope for a snake and is frightened, so the ignorant mistake the body and other not-self things for the Self and are caught in the bondage of worldly existence. But when he sees clearly, he knows, ‘This is just a rope, not a snake,’ and his fear vanishes. Similarly, when one knows the Self, bondage ceases.”

— Vivekacūḍāmaṇi 141-142 (paraphrase)

There is no snake to kill—only a misperception to correct. There is no sin to confess—only ignorance to dispel.

The Practice of Discrimination

If the problem is ignorance, the solution is viveka—discrimination, discernment. You learn to distinguish the Self from what is not-self:

“The seer is pure consciousness only; though pure, he appears to see through the mental organ (buddhi). The modifications of the mental organ are always known by its master, the puruṣa, whose nature is unchanging.”

— Yoga Sūtras 2.20, 4.18 (trans. Bryant)

(The Yoga Sūtras come from the Sāṃkhya-Yoga tradition rather than Vedānta, but they share the distinction between pure consciousness—puruṣa—and everything else.)

The practitioner watches the mind’s modifications (vṛttis) arise and pass, recognizing: “I am not that. I am the witness.” This resembles Buddhist mindfulness but with a crucial difference: the Buddhist watches phenomena without positing a witness; the Hindu meditator watches phenomena in order to identify with the witness.

“The wise one should draw up the self by the self, and not let the self sink down; for the self alone is the friend of the self, and the self alone is the enemy of the self.”

— Bhagavad Gītā 6.5 (trans. Sargeant)

There are two “selves” here: the lower self (the psychological self, the ego) and the higher Self (ātman). Self-knowledge means the higher Self recognizing itself, freeing itself from identification with the lower.

The Difference from Christian Excavation

Both the Christian and the Hindu traditions posit something hidden—but the nature of the hidden and the method of revelation differ fundamentally.

For the Christian, what is hidden is desire—specifically, disordered desire, the will turned away from God. The hidden thing is bad, and bringing it to speech is purifying.

For the Hindu (in the Advaita tradition), what is hidden is pure consciousness—the ātman that was never touched by desire, never affected by action, never stained by sin. The hidden thing is already perfect, and the practice is not excavation but recognition.

You do not confess your way to ātman. You discriminate your way there—by progressively recognizing that everything you can observe is not-self until only the observer remains.

Part IV: A Comparative Table

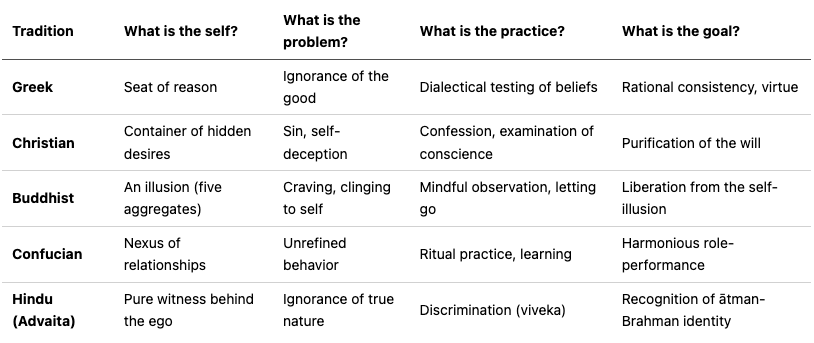

We now have five psychologies to compare:

Each tradition locates the problem differently, and therefore prescribes different practices. Notice that only the Christian tradition treats hidden desire as the central problem and verbal confession as the central practice. The others either deny hidden depths (Buddhism, Confucianism) or locate the hidden truth in a radically different place (Hinduism: the hidden truth is not your desires but your transcendence of all desire).

Part V: What This Means for Us

The Therapeutic Inheritance

Modern Western therapy inherits the Christian topology: the self as container of hidden contents, speech as the instrument of excavation, the professional listener (priest → analyst → therapist) as facilitator of truth-production.

Freud made this explicit. The unconscious contains repressed desires; analysis brings them to speech; the talking cure heals. The entire apparatus—even stripped of religious content—is structurally Christian: confess, and you shall be healed.

But if the other traditions are right—or even partially right—then this apparatus may be solving a problem it helps create. Perhaps the self is not as deep as we think. Perhaps the endless excavation produces the depths it claims to discover. Perhaps “processing” emotions through verbalization is not a universal human need but a particular cultural practice with particular costs and benefits.

Alternative Therapies

Consider what therapy might look like under each alternative model:

Greek therapy would focus on beliefs. Are your values coherent? Can you give a rational account of what you think is good? Cognitive-behavioral therapy has something of this character—it targets thoughts, not depths.

Buddhist therapy would focus on observation without identification. Watch the anxiety arise; note “anxiety”; let it pass. Do not ask what it means about you. Mindfulness-based therapies have something of this character—though they are often re-grafted onto the Christian model (”be mindful so you can discover your true feelings”).

Confucian therapy would focus on behavior and relationship. Are you fulfilling your roles well? What practices might reshape your conduct? Some forms of family systems therapy and behavioral therapy have this character—but they rarely abandon the assumption of hidden depths entirely.

Hindu therapy would focus on disidentification. You are not your anxiety. You are not your trauma. You are the witness of all these things, untouched by them. Some transpersonal therapies gesture in this direction—but the radical claim that the true Self is already free is rarely taken seriously.

Holding the Models Lightly

The point is not to choose a winner but to gain freedom. Each model illuminates something; each has blind spots.

The Christian model takes seriously the reality of self-deception—that we can want things we do not admit to wanting, that our stated reasons are not always our real reasons. This is genuinely true and genuinely important.

The Buddhist model takes seriously the possibility that the self is less substantial than we think—that much of our suffering comes from over-identification with thoughts and feelings that are actually transient. This too is true and important.

The Confucian model takes seriously the role of practice and relationship in forming the self—that we are shaped more by what we do and who we do it with than by what we introspect. Also true.

The Hindu model takes seriously the possibility of a dimension of consciousness that is not touched by the turmoil of ordinary experience—a witness that observes without being harmed. Whether this is true is harder to say, but it is at least a coherent possibility.

The Greek model takes seriously the role of reason and argument in self-understanding—that you know yourself by articulating and testing your commitments. This remains valuable even if incomplete.

The Freedom of Multiplicity

To see that there are multiple ways of being a self—multiple psychologies, multiple practices, multiple goals—is itself liberating. You do not have to dig. You do not have to confess. You do not have to find your “true self” hidden beneath layers of defense.

You might instead: observe phenomena without ownership (Buddhist). Refine your conduct through practice (Confucian). Discriminate between witness and witnessed (Hindu). Test your beliefs for coherence (Greek).

Or you might confess (Christian). The point is that you now choose rather than assume—that you hold your practices as tools rather than necessities, and can reach for different tools when different tasks require them.

The history of self-relation is a history of possibilities. We have barely begun to explore them.

Selected Sources

Buddhist Texts:

-

Anattalakkhana Sutta, Samyutta Nikaya 22.59

-

Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta, Majjhima Nikaya 10

-

Bāhiya Sutta, Udana 1.10

-

Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, Samyutta Nikaya 56.11

-

Translations primarily from Bhikkhu Bodhi

Confucian Texts:

-

Analects (trans. Slingerland)

-

Mencius (trans. Van Norden)

-

Xunzi (trans. Watson)

Hindu Texts:

-

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upanishad (trans. Olivelle)

-

Chāndogya Upanishad (trans. Olivelle)

-

Kaṭha Upanishad (trans. Olivelle)

-

Bhagavad Gītā (trans. Sargeant)

-

Yoga Sūtras (trans. Bryant)

-

Śaṅkara, Vivekacūḍāmaṇi

Secondary Literature:

-

Collins, Steven. Selfless Persons: Imagery and Thought in Theravāda Buddhism

-

Fingarette, Herbert. Confucius: The Secular as Sacred

-

Rambachan, Anantanand. The Advaita Worldview

-

Slingerland, Edward. Effortless Action: Wu-wei as Conceptual Metaphor