Know Thyself: Gurdjieff, Kierkegaard, Eckhart

Published 2025-12-16-

Pt 1: Greek vs Christian

-

Pt 3: Gurdjieff, Kierkegaard, Eckhart

-

Pt 4: No Self

Gurdjieff, Kierkegaard, and Eckhart on the Self

“Man has no individual I. But there are, instead, hundreds and thousands of separate small I’s, very often entirely unknown to one another.” — G.I. Gurdjieff, recorded in Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous

Introduction: The Exceptions That Prove the Rules

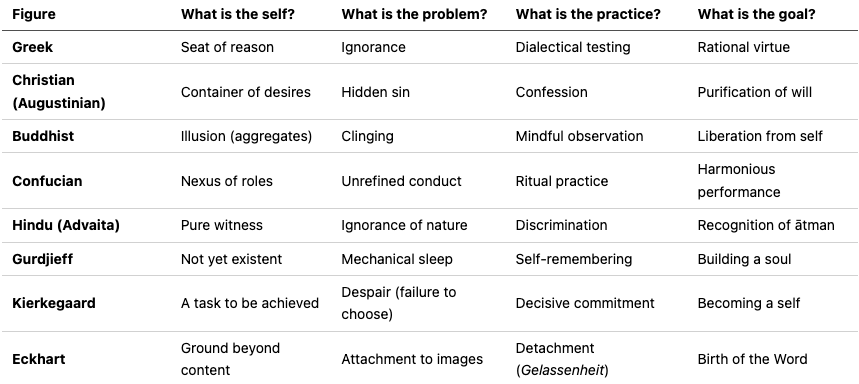

The previous essays traced five psychologies of self-knowledge: Greek (rational audit), Christian (excavating desire), Buddhist (dissolving the self-illusion), Confucian (perfecting relational performance), and Hindu (discriminating the witness). Each represents a coherent tradition with characteristic practices.

But intellectual history is never so tidy. Three figures complicate this taxonomy in illuminating ways: G.I. Gurdjieff (1866–1949), Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855), and Meister Eckhart (c. 1260–1328). Each draws on one or more of these traditions but twists it into something new.

Gurdjieff says: You don’t have a self to know—not because the self is an illusion (Buddhist), but because you haven’t built one yet.

Kierkegaard says: The self is not given but achieved—you become yourself through choice, not through introspection.

Eckhart says: The soul must be emptied even of God—the deepest ground is beyond both confession and discrimination.

Together, they suggest that the question “how do I know myself?” may already be malformed.

Part I: Gurdjieff—The Self You Don’t Yet Have

The Diagnosis: Mechanical Multiplicity

Gurdjieff’s teaching begins with a brutal assessment: ordinary human beings do not possess the unity they assume they have. What we call “I” is actually a crowd of competing impulses, each calling itself “I” when it happens to be in charge:

“Man has no individual I. But there are, instead, hundreds and thousands of separate small I’s, very often entirely unknown to one another, never coming into contact, or, on the contrary, hostile to each other, mutually exclusive and incompatible. Each minute, each moment, man is saying or thinking ‘I.’ And each time his I is different. Just now it was a thought, now it is a desire, now a sensation, now another thought, and so on, endlessly. Man is a plurality. Man’s name is legion.”

— Gurdjieff, recorded in P.D. Ouspensky, In Search of the Miraculous (1949)

This resembles Buddhist no-self doctrine—the self is revealed as fragmented upon examination. But Gurdjieff’s conclusion is opposite. The Buddhist says: see through the illusion of self and be liberated. Gurdjieff says: you are not yet a self, and you must become one through work.

“A man has no permanent and unchangeable I. Every thought, every mood, every desire, every sensation, says ‘I.’ And in each case it seems to be taken for granted that this I belongs to the Whole, to the whole man, and that a thought, a desire, or an aversion is expressed by this Whole. In actual fact there is no foundation whatsoever for this assumption.”

— In Search of the Miraculous

The Condition: Sleep

The reason we lack unity is that we are asleep—not literally, but in a precise technical sense. We move through life in a state of waking sleep, acting mechanically, reacting to stimuli without awareness:

“Man is a machine. All his deeds, actions, words, thoughts, feelings, convictions, opinions, and habits are the results of external influences, external impressions. Out of himself a man cannot produce a single thought, a single action. Everything he says, does, thinks, feels—all this happens.”

— In Search of the Miraculous

The Greek assumed we could simply turn reason on ourselves and examine our beliefs. The Christian assumed we had a unified will (even if corrupt) that could confess. Gurdjieff denies both assumptions. The machine cannot examine itself; it can only react. There is no unified agent to confess—only a sequence of mechanical responses.

The Practice: Self-Observation and Self-Remembering

If we are machines, how can change be possible? Gurdjieff’s answer is that a small part of us is not entirely mechanical—attention can be directed consciously, and this creates a foothold:

“Self-observation brings man to the realization of the necessity for self-change. And in observing himself a man notices that self-observation itself brings about certain changes in his inner processes. He begins to understand that self-observation is an instrument of self-change, a means of awakening.”

— In Search of the Miraculous

Self-observation in Gurdjieff’s sense is not introspection in the Christian sense. You are not asking “what did I really want?” or “what was my hidden motive?” You are watching the machine operate—noting which “I” is speaking, what center (intellectual, emotional, moving, instinctive) is activated, what mechanical pattern is running.

The more advanced practice is self-remembering—a simultaneous awareness of self and world:

“Self-remembering is an attempt to be aware of yourself, to be aware of your own presence, at the same time as you are aware of the external world. Normally, when we are absorbed in life, we forget ourselves completely. Self-remembering is dividing attention, giving some of it to yourself.”

— Gurdjieff, paraphrased from various sources

This is not Buddhist mindfulness (watching phenomena without ownership) nor Christian examination (probing for hidden desires). It is an active effort to be present, to not disappear into mechanical reaction.

The Goal: Building a Soul

For Gurdjieff, the goal is not liberation from self (Buddhist) or purification of self (Christian) but construction of a self. Humans are born with the possibility of a soul but not its actuality:

“Man is born without a soul. He can acquire a soul only by conscious work on himself. A soul is something that must be grown, crystallized, formed through intentional suffering and conscious labor.”

— Gurdjieff, paraphrased from Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson

This is shocking from any traditional religious perspective. The Christians assume you have a soul to save; the Buddhists assume you have a self-illusion to dissolve. Gurdjieff says you have neither—you have only potential, and most people die without actualizing it.

The “Work” (as Gurdjieff’s teaching is often called) is precisely this: the conscious labor of building a unified self out of the chaos of mechanical reactions.

The Difference

Gurdjieff stands outside the confession-excavation model entirely. You cannot confess your hidden desires because you do not have a unified “you” with coherent desires. The multiple I’s have contradictory desires; asking “what do I really want?” assumes a unity that does not exist.

But he also stands outside the Buddhist model. The Buddhist practices non-identification with phenomena because the self is an illusion to be seen through. Gurdjieff practices self-observation as a technique for building a self. The goal is not dissolution but crystallization.

“Remember yourself always and everywhere.”

— Gurdjieff’s primary injunction

Part II: Kierkegaard—Becoming a Self Through Choice

The Self as Task

Kierkegaard shares something with Gurdjieff: the conviction that selfhood is not given but achieved. But where Gurdjieff frames this in terms of building psychological unity, Kierkegaard frames it in terms of choice and commitment.

The opening of The Sickness Unto Death offers Kierkegaard’s formal definition of the self:

“The self is a relation that relates itself to itself... A human being is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity. In short, a synthesis. A synthesis is a relation between two. Considered in this way, a human being is not yet a self.”

— The Sickness Unto Death (1849), trans. Hong and Hong

A human being is a synthesis—but not yet a self. The self emerges only when the synthesis relates itself to itself, when it takes responsibility for what it is. You become a self by owning your existence.

Despair: The Failure to Become a Self

For Kierkegaard, the fundamental human problem is not ignorance (Greek), sin in the confessional sense (Christian), craving (Buddhist), or mechanical sleep (Gurdjieff). It is despair—and despair is precisely the failure to become a self:

“Despair is the sickness unto death... The torment of despair is precisely this inability to die. It has more in common with the situation of a mortally ill person who lies in the agony of death but cannot die. To be sick unto death is to be unable to die, yet not as if there were hope of life; no, the hopelessness is that even the last hope, death, is gone.”

— The Sickness Unto Death

Despair comes in forms: not knowing you have a self (unconscious despair), not willing to be oneself (despair of weakness), and defiantly willing to be oneself without God (despair of defiance). All are failures of the self-relation.

“The formula that describes the state of the self when despair is completely rooted out is this: in relating itself to itself and in willing to be itself, the self rests transparently in the power that established it.”

— The Sickness Unto Death

This “power that established it” is God. For Kierkegaard, becoming a self is not a purely autonomous project—it requires grounding in the transcendent. But this is not the God of confession manuals; it is the God before whom one exists as an individual, making ultimate choices.

The Three Stages: Aesthetic, Ethical, Religious

Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous works map three “stages on life’s way,” each representing a different mode of existence:

The aesthetic life is the life of immediacy—sensation, pleasure, variety. The aesthete avoids commitment, maintains ironic distance, refuses to choose:

“My melancholy is the most faithful mistress I have known—no wonder, then, that I return the love.”

— Either/Or (1843), the papers of “A”

The ethical life is the life of commitment and duty. The ethicist chooses, takes responsibility, marries, works, accepts roles:

“The act of choosing is essentially a proper and stringent expression of the ethical... When one does not choose absolutely, one chooses only for the moment, and therefore can choose something different the next moment.”

— Either/Or, Judge William’s letters

The religious life transcends both—not by abandoning the ethical but by grounding it in a relation to the absolute. The “knight of faith” makes the absurd movement of believing against all reason:

“The knight of faith knows it gives infinite satisfaction to let go of oneself and become nothing in the hand of the infinite... But he also knows that this gives no rest to his soul... He knows that it is more blessed to give than to receive. He knows the happiness of being able to give infinite thanks to God for what has been given him.”

— Fear and Trembling (1843), trans. Hong and Hong

Choice, Not Introspection

Notice what is absent from Kierkegaard: the injunction to excavate hidden desires. The aesthetic avoids choosing; the ethical chooses; the religious chooses ultimately. The question is not “what do I really want?” but “what will I commit to?”

“The most tremendous thing that has been granted to man is: the choice, freedom.”

— The Journals

Self-knowledge for Kierkegaard is not archaeological but decisional. You do not find yourself by digging into your past; you create yourself by committing to a future. The self is not a buried treasure but a project.

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

— The Journals

This does not mean introspection is worthless—Kierkegaard was himself an obsessive self-examiner. But the point of examination is not to uncover hidden contents; it is to clarify what decision is being avoided, what commitment is being deferred, what self is failing to become.

Subjectivity as Truth

Kierkegaard’s famous formula—”truth is subjectivity”—does not mean truth is whatever you feel. It means that certain truths (specifically, existential and religious truths) are only true for you if you appropriate them in passionate commitment:

“The objective accent falls on WHAT is said, the subjective accent on HOW it is said... At its maximum this inward ‘how’ is the passion of the infinite, and the passion of the infinite is truth. But the passion of the infinite is precisely subjectivity, and thus subjectivity becomes truth.”

— Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846), trans. Hong and Hong

You can know objectively that you will die—but have you appropriated this truth? Do you live in light of it? The Christian can recite the creeds objectively—but is there subjective appropriation, inward transformation?

Self-knowledge in this sense is not about contents (what do I believe? what do I want?) but about mode of existence (how do I relate to what I already know?).

Part III: Meister Eckhart—Emptiness at the Ground

A Different Christian Voice

Meister Eckhart is a Christian mystic, a Dominican preacher and theologian. But his psychology differs radically from the Augustinian confession model. Where Augustine probes hidden desires, Eckhart demands radical detachment—even detachment from God.

“Man’s last and highest leave-taking is leaving God for God.”

— Sermon 52, trans. Walshe

This is among the most radical statements in Christian literature. The soul must let go even of its images of God, even of its desire for God, in order to reach the “ground” where soul and God are one.

The Ground of the Soul

Eckhart posits a depth in the soul that is beyond all faculties—beyond intellect, will, memory. He calls it the Seelengrund or Seelenfünklein (the “spark” of the soul):

“There is something in the soul so closely akin to God that it is already one with Him and need never be united to Him... This something is so intimately one with God that it is already one with Him in unity, not merely in union... It is free of all names and forms, entirely exempt and free, as God is exempt and free in Himself.”

— Sermon 48, trans. Walshe

This resembles the Hindu ātman—a dimension of the soul that is untouched by temporal experience, already one with the divine ground. But Eckhart remains Christian: this ground is where the Trinity is born, where the Word speaks eternally.

“In this essence of God the Father bears his only-begotten Son, and in this same essence the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son... In this ground the soul is equal with God and not beneath him.”

— German sermon, paraphrased

Detachment: Beyond Confession

The key practice for Eckhart is Abgeschiedenheit—detachment, releasement. This is not the examination of desires but the letting go of all desires, all images, all attachments:

“The most powerful prayer, one wellnigh omnipotent, and the worthiest work of all is the outcome of a detached mind. The more detached the mind, the more powerful, worthy, useful, praiseworthy, and perfect the prayer and work become. A detached mind can do all things.”

— “On Detachment,” trans. Walshe

Augustine would have you confess your desires to purify them. Eckhart would have you release them entirely—not by understanding them but by letting them go.

“I have said at times that the best thing is to leave God for God... The best and noblest thing that a man can arrive at in this life is to remain silent and let God speak and act.”

— Sermon 52

The confessional model assumes that speech extracts hidden truth. Eckhart suggests that silence reaches deeper than speech—that the soul’s ground is beyond what can be spoken.

The Birth of the Word in the Soul

Eckhart’s positive teaching centers on the birth of the Word (the Son, the Logos) in the soul:

“What is the use of the eternal birth of the Son if it does not take place in me? Everything depends on this... The Father begets his Son in the soul in the very same way as he begets him in eternity, neither more nor less.”

— Sermon 1, trans. Walshe

This is not metaphorical. Eckhart means that the same eternal generation by which the Father begets the Son in the Trinity occurs in the detached soul. The soul becomes the site of divine self-expression.

But for this to happen, the soul must be empty:

“God can only work in and with nothingness. If you would have the Word of God, you must give up all that is your own and become as a desert... When I preach, I am wont to speak of detachment, and that a man should be free of all things and all happenings.”

— Sermon 28

The Christian confession model fills the soul with speech about itself. Eckhart empties the soul of all content—including speech, including self-knowledge—so that God may speak.

The Difference from Buddhist Emptiness

Eckhart has often been compared to Buddhism (and to Advaita Vedanta), and the parallels are real: detachment, emptiness, the ground beyond subject and object. But there are differences.

The Buddhist empties the self of the illusion of self—there is no ātman, no soul, no ground. What remains is sunyata (emptiness) or the flow of dependent origination.

Eckhart empties the self of its attachments and images—but what remains is not nothing. It is the ground where soul and Godhead are one, where the Word is born, where the Trinity eternally generates. The emptiness is not void but plenitude.

“God’s ground and the soul’s ground are one ground.”

— German sermon, paraphrased

For the Buddhist, emptiness is the final word. For Eckhart, emptiness is the condition for fullness—the desert that flowers when God acts.

Beyond Introspection

Eckhart offers a Christian path that bypasses confession entirely. You do not examine your desires; you let go of them. You do not speak your hidden truth; you fall silent so God may speak. You do not dig into the self; you abandon the self.

“If anyone went on for a thousand years asking of life: ‘Why are you living?’ life, if it could answer, would only say: ‘I live so that I may live.’ That is because life lives out of its own ground and springs from its own source, and so it lives without asking why it is itself living.”

— Sermon 5b

The self that lives from its ground does not need to ask why. It does not need to confess. It does not need to know itself in the archaeological sense. It simply lives—transparent to the divine ground, the Word speaking through it.

Part IV: What These Three Add

Gurdjieff’s Contribution

Gurdjieff shatters the assumption that there is already a self to know. The Christian says: confess your unified but fallen will. Gurdjieff says: you have no unified will—you are a crowd of competing impulses. Before you can ask “what do I want?” you must build a “you” capable of coherent wanting.

This reframes the entire project. Self-knowledge is not excavation of existing contents but construction of a new unity. The practice is not confession but self-observation and self-remembering—techniques for waking up from mechanical sleep.

Kierkegaard’s Contribution

Kierkegaard shifts the question from “what do I find inside?” to “what do I choose to become?” Self-knowledge is not archaeological but decisional. The self is a task, not a given.

This means that endless introspection can be a form of avoidance—a way of deferring the choice that would actually constitute a self. The aesthete analyzes his moods; the ethicist commits to a life. The question is not “what do I really want?” but “what will I stake my existence on?”

Eckhart’s Contribution

Eckhart suggests that the deepest dimension of the soul is beyond what introspection can reach. The ground of the soul is not hidden content to be excavated but a depth beyond all content—a place where subject and object, self and God, are not yet divided.

Confession deals with the surface—desires, sins, intentions. Eckhart points to a ground beneath desire, beneath intention, beneath the self that could confess. The path is not speech but silence, not examination but releasement.

Part V: A Revised Map

We now have eight positions to compare. But the comparison is no longer a simple taxonomy; these three figures show that the traditions can be mixed, inverted, and transcended.

The Question Behind the Question

These eight positions suggest that “how do I know myself?” is not a single question but several:

-

Is there a self to know? (Buddhist: no. Gurdjieff: not yet. Others: yes, in various senses.)

-

What kind of thing is it? (Greek: rational agent. Christian: desiring will. Hindu: pure witness. Eckhart: ground beyond subject/object.)

-

What is wrong with our current condition? (Ignorance? Sin? Craving? Sleep? Despair? Attachment?)

-

What practice addresses the problem? (Dialectic? Confession? Meditation? Ritual? Self-remembering? Choice? Detachment?)

-

What is the goal? (Virtue? Purification? Liberation? Harmony? Recognition? Unity? Becoming? Union?)

Each answer ramifies into a different form of life, a different set of practices, a different conception of human flourishing.

Part VI: The Practical Upshot

Against Monoculture

The danger of inheriting a single psychology—especially unconsciously—is that it becomes invisible. If you assume that self-knowledge means excavating hidden desires, you will spend your life digging. If you assume it means rational audit, you will spend your life testing beliefs. If you assume there is no self to know, you will practice non-identification.

But what if you are digging when you should be building (Gurdjieff)? What if you are analyzing when you should be choosing (Kierkegaard)? What if you are speaking when you should be silent (Eckhart)?

A Differential Diagnosis

Perhaps different problems call for different approaches:

-

If you suffer from incoherent beliefs, Greek dialectic may help.

-

If you suffer from hidden self-deception about motives, Augustinian examination may help.

-

If you suffer from over-identification with passing states, Buddhist mindfulness may help.

-

If you suffer from poor relational conduct, Confucian practice may help.

-

If you suffer from confusion about your deepest nature, Hindu discrimination may help.

-

If you suffer from mechanical fragmentation, Gurdjieffian self-observation may help.

-

If you suffer from failure to commit, Kierkegaardian decision may help.

-

If you suffer from attachment even to spiritual goals, Eckhartian detachment may help.

The assumption that one practice fits all conditions is the error.

The Freedom of Multiplicity (Again)

To hold all eight models in mind is not eclecticism—it is liberation. You are no longer trapped in one room of the house, digging in the basement because someone told you the treasure was there.

Perhaps the treasure is in the basement. Perhaps there is no treasure. Perhaps you must build the treasure. Perhaps you must stop looking for treasure and let the treasure find you.

The history of self-relation is a history of experiments. We are still running them.

Coda: A Composite Vision

Imagine a person who has absorbed all eight teachings—not as contradictions but as aspects of a complex whole:

She knows that some beliefs should be tested for coherence (Greek).

She knows that some desires are hidden and self-deceived, and that speech can surface them (Christian).

She knows that some suffering comes from clinging to a self that is less solid than it seems (Buddhist).

She knows that some of who she is emerges from roles and relationships, and practice shapes the practitioner (Confucian).

She knows that behind the turbulence of thought and feeling, awareness itself remains (Hindu).

She knows that her sense of being a unified agent is partly illusion—that she is more fragmented than she likes to think—and that building coherence requires work (Gurdjieff).

She knows that endless self-analysis can be a way of avoiding commitment, and that sometimes she must simply choose (Kierkegaard).

She knows that beneath all this—beneath belief, desire, phenomena, roles, witness, unity, and choice—there is a ground where she and the source of things are not two, and that she touches it not by seeking but by letting go (Eckhart).

Such a person would have many tools. She would not confuse the map for the territory, nor the tool for the hand that wields it.

She would know herself—not as a fixed object known, but as an ongoing process of knowing, in which each tradition illuminates one facet of an inexhaustible question.

Selected Sources

Gurdjieff:

-

Ouspensky, P.D. In Search of the Miraculous (1949)

-

Gurdjieff, G.I. Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (1950)

-

Gurdjieff, G.I. Meetings with Remarkable Men (1963)

Kierkegaard:

-

Either/Or (1843), trans. Hong and Hong

-

Fear and Trembling (1843), trans. Hong and Hong

-

Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846), trans. Hong and Hong

-

The Sickness Unto Death (1849), trans. Hong and Hong

-

The Journals of Kierkegaard, trans. Dru

Meister Eckhart:

-

Meister Eckhart: The Essential Sermons, trans. Colledge and McGinn

-

Meister Eckhart: German Sermons and Treatises, trans. Walshe

-

McGinn, Bernard. The Mystical Thought of Meister Eckhart

Secondary:

-

Needleman, Jacob. Lost Christianity (connects Gurdjieff to esoteric Christian tradition)

-

Caputo, John D. The Mystical Element in Heidegger’s Thought (on Eckhart’s influence)

-

Hannay, Alastair. Kierkegaard: A Biography