Know Thyself: No Self

Published 2025-12-17

-

Pt 1: Greek vs Christian

-

Pt 4: No Self

-

Pt 5: Through What?

-

Pt 6: The Kingdom Within

“The fish trap exists because of the fish. Once you’ve gotten the fish, you can forget the trap. Words exist because of meaning. Once you’ve gotten the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find a man who has forgotten words so I can have a word with him?” — Zhuangzi, Chapter 26

Introduction: Questioning the Question

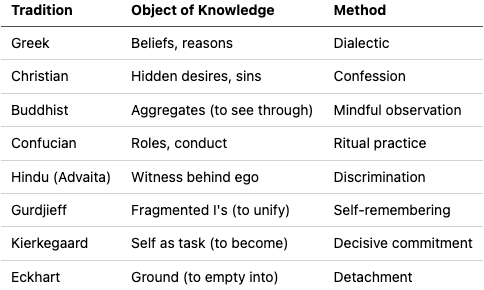

The previous essays mapped eight psychologies of self-knowledge, from Greek rational audit to Eckhartian detachment. Despite their differences, they share certain assumptions: that there is something called “the self,” that it is in some sense the proper object of inquiry or practice, and that some method—dialectic, confession, meditation, ritual, self-remembering, choice, or releasement—can bring us into right relation with it.

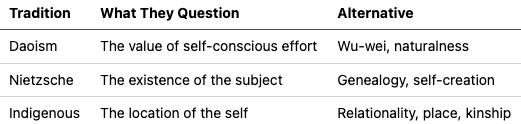

This essay examines three perspectives that challenge these shared assumptions at a deeper level.

Daoism asks: What if the very effort to know yourself is what prevents naturalness? What if trying is the problem?

Nietzsche asks: What if “the self” is a grammatical fiction? What if the desire for self-knowledge is itself a symptom to be diagnosed rather than a goal to be achieved?

Indigenous relational ontologies ask: What if the self isn’t located inside you at all? What if “who am I?” can only be answered by “whose am I?”—whose descendant, whose relative, whose place?

These are not merely additional options on the menu. They question whether the menu makes sense.

Part I: Daoism—The Art of Not Trying

The Uncarved Block

The Dao De Jing, attributed to Laozi (traditionally 6th century BCE, though the text is likely later), opens by undermining the project of articulation:

“The Dao that can be told is not the eternal Dao. The name that can be named is not the eternal name. The nameless is the beginning of heaven and earth. The named is the mother of ten thousand things.”

— Dao De Jing, Chapter 1 (trans. Addiss and Lombardo)

If the Dao cannot be spoken, then a fortiori, the self—as an expression of Dao—cannot be fully captured in words. The Augustinian project of verbal confession, the Socratic project of giving an account, the Buddhist project of systematic observation—all assume that articulation brings clarity. Daoism is skeptical.

The ideal state is pu—the “uncarved block,” the condition of natural simplicity before culture, learning, and self-consciousness have complicated things:

“Return to the state of the uncarved block. When the block is carved, it becomes useful. When the sage uses it, he becomes the ruler of the officials. Thus the greatest carving does no cutting.”

— Dao De Jing, Chapter 28

The implication for self-knowledge is counterintuitive: the more you analyze, categorize, and articulate yourself, the further you move from your original nature. The Confucian project of self-cultivation through learning and ritual is, from the Daoist perspective, a kind of damage.

Wu-Wei: Non-Action

The central Daoist concept is wu-wei—often translated as “non-action” but better understood as “effortless action” or “non-forcing.” It does not mean doing nothing; it means acting without the interference of anxious, calculating, self-conscious effort:

“The Dao does nothing, yet nothing is left undone. If kings and lords could keep to it, the ten thousand things would transform by themselves.”

— Dao De Jing, Chapter 37

“In the pursuit of learning, every day something is acquired. In the pursuit of Dao, every day something is dropped. Less and less is done until non-action is achieved. When nothing is done, nothing is left undone.”

— Dao De Jing, Chapter 48

Notice the inversion: the path to the Dao is not accumulation (more self-knowledge, more insight, more purification) but subtraction. You do not add practices; you drop them. You do not gain self-knowledge; you lose self-consciousness.

This directly opposes the Gurdjieffian project of building a self through conscious effort, the Kierkegaardian project of becoming a self through decisive commitment, and the Christian project of purifying the self through confession. For Laozi, all these efforts—however noble—are still efforts, and effort is the problem.

Zhuangzi: The Uselessness of the Useful

Zhuangzi (c. 369–286 BCE) radicalizes Laozi with humor, paradox, and anarchic imagination. Where the Dao De Jing is gnomic and terse, the Zhuangzi is wild and playful—and far more explicitly critical of the self-knowledge project.

The famous story of Cook Ding illustrates wu-wei in action:

“Cook Ding was cutting up an ox for Lord Wen-hui. At every touch of his hand, every heave of his shoulder, every move of his feet, every thrust of his knee—zip! zoop! He slithered the knife along with a zing, and all was in perfect rhythm, as though he were performing the dance of the Mulberry Grove or keeping time to the Ching-shou music.

‘Ah, this is marvelous!’ said Lord Wen-hui. ‘Imagine skill reaching such heights!’

Cook Ding laid down his knife and replied, ‘What I care about is the Dao, which goes beyond skill. When I first began cutting up oxen, all I could see was the ox itself. After three years I no longer saw the whole ox. And now—now I meet it with my spirit and don’t look with my eyes. Perception and understanding have come to a stop and spirit moves where it wants.’”

— Zhuangzi, Chapter 3 (trans. Watson)

Cook Ding does not analyze the ox; he meets it with spirit (shen). His skill came not from more knowledge but from a kind of forgetting—perception and understanding “came to a stop.” This is the opposite of introspection.

Zhuangzi applies this to the self explicitly:

“You have heard of the knowledge that knows, but you have never heard of the knowledge that does not know. Look into that closed room, the empty chamber where brightness is born! Fortune and blessing gather where there is stillness. But if you do not keep still—this is what is called sitting but racing around. Let your ears and eyes communicate with what is inside, and put mind and knowledge on the outside. Then even gods and spirits will come to dwell, not to speak of men!”

— Zhuangzi, Chapter 4 (trans. Watson)

“The knowledge that does not know”—this is not ignorance but a mode of being in which the grasping, categorizing mind has released its grip. You do not know yourself by looking harder; you know yourself by stopping the looking.

The Centipede’s Legs

One of Zhuangzi’s most famous parables directly targets the project of self-examination:

“The centipede was happy, quite, Until a toad in fun Said, ‘Pray, which leg goes after which?’ This worked his mind to such a pitch, He lay distracted in a ditch, Considering how to run.”

— Traditional paraphrase of Zhuangzi

The centipede walks perfectly well until he starts analyzing how he walks. The analysis produces paralysis. Zhuangzi’s point is that much of what we do well, we do without self-conscious attention—and self-conscious attention can destroy the very capacity it aims to understand.

This is a direct challenge to every introspective psychology. The Christian examines conscience; the Buddhist observes phenomena; the Gurdjieffian practices self-remembering. All assume that more attention to the self produces better results. Zhuangzi suggests the opposite: the self functions best when it forgets itself.

The Self as Transformation

For Zhuangzi, the self is not a fixed thing to be known but a process of transformation:

“Once Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering about, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. He didn’t know he was Zhuang Zhou. Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable Zhuang Zhou. But he didn’t know if he was Zhuang Zhou who had dreamed he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuang Zhou. Between Zhuang Zhou and a butterfly there must be some distinction! This is called the Transformation of Things.”

— Zhuangzi, Chapter 2 (trans. Watson)

The butterfly dream is not a puzzle to be solved but a provocation: Why do you assume the waking self is more real than the dreaming self? Why do you assume there is a fixed “Zhuangzi” to be known at all? The “Transformation of Things” (wu hua) suggests that reality is a ceaseless flux of perspectives, and the attempt to fix a stable self is a mistake.

This goes beyond Buddhist no-self doctrine. The Buddhist says: there is no self, only aggregates. Zhuangzi says: there are only transformations, and who is asking? Even the question “who am I?” assumes a questioner stable enough to receive an answer. But what if the questioner is also transforming?

Part II: Nietzsche—Unmasking the Unmaskers

The Fiction of the Subject

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) launches a different kind of assault on self-knowledge. Where Daoism suggests that the self is better left unexamined, Nietzsche argues that “the self” is a grammatical illusion—a fiction produced by language.

“There is no ‘being’ behind doing, effecting, becoming; ‘the doer’ is merely a fiction added to the deed—the deed is everything.”

— On the Genealogy of Morals, Essay I, Section 13 (trans. Kaufmann)

We say “lightning flashes”—but there is no lightning separate from the flash. The grammar of subject and predicate tricks us into positing a “doer” behind every “deed.” Similarly, we say “I think”—but there is no “I” separate from the thinking. The self is a grammatical artifact.

“A thought comes when ‘it’ wishes, not when ‘I’ wish, so that it is a falsification of the facts to say that the subject ‘I’ is the condition of the predicate ‘think.’ It thinks: but that this ‘it’ is precisely that old famous ‘I’ is, to put it mildly, only an assumption, an assertion, above all not an ‘immediate certainty.’”

— Beyond Good and Evil, Section 17 (trans. Kaufmann)

If there is no stable “I” behind experience, then the project of self-knowledge is chasing a phantom. You cannot excavate hidden desires because there is no unified agent whose desires they are. You cannot confess your true motives because “your” motives are not yours—they are impersonal forces that grammar has misleadingly assigned to a fictitious subject.

Genealogy: History Instead of Depth

Nietzsche’s alternative to introspection is genealogy—the historical investigation of how our values, concepts, and self-interpretations came to be:

“Under what conditions did man devise these value judgments good and evil? And what value do they themselves possess? Have they hitherto hindered or furthered human prosperity? Are they a sign of distress, of impoverishment, of the degeneration of life? Or is there revealed in them, on the contrary, the plenitude, force, and will of life, its courage, certainty, future?”

— On the Genealogy of Morals, Preface, Section 3

The question is not “what do I really believe?” (Socratic) or “what do I really want?” (Augustinian) but “where did this belief come from? What historical forces produced it? Whose interests does it serve?”

This is unmasking rather than confession. The Christian confesses guilt to be absolved. Nietzsche unmasks guilt as a strategy—specifically, a strategy of the weak to gain power over the strong:

“The slave revolt in morality begins when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values: the ressentiment of natures that are denied the true reaction, that of deeds, and compensate themselves with an imaginary revenge.”

— On the Genealogy of Morals, Essay I, Section 10

The person who “examines their conscience” is not accessing some deep truth about themselves; they are performing a historically conditioned ritual that serves particular interests. The very desire to confess, to feel guilty, to seek purification—this desire has a history, and that history is not innocent.

The Will to Truth as Will to Power

Most radically, Nietzsche questions the value of truth itself—including self-knowledge:

“The will to truth, which will still tempt us to many a venture, that famous truthfulness of which all philosophers so far have spoken with respect—what questions has this will to truth not laid before us! What strange, wicked, questionable questions! ... What in us really wants ‘truth’?”

— Beyond Good and Evil, Section 1

Why do you want to know yourself? What is this desire for self-knowledge? Nietzsche’s answer: it is a form of the will to power. The drive for truth is not disinterested—it is a way of gaining control, of mastering what was chaotic, of imposing order on flux.

“Physics, too, is only an interpretation and arrangement of the world (according to ourselves, if I may say so!) and not an explanation of the world.”

— Beyond Good and Evil, Section 14

If even physics is interpretation “according to ourselves,” how much more so is self-knowledge? The “self” you discover through introspection is not a pre-existing object you have finally uncovered; it is an artifact of the interpretive process, shaped by the interests that drove you to look in the first place.

Becoming Who You Are

This might sound like nihilism, but Nietzsche’s positive teaching is amor fati—love of fate—and the injunction to “become who you are”:

“What does your conscience say? — ‘You shall become the person you are.’”

— The Gay Science, Section 270 (trans. Kaufmann)

This is not the Kierkegaardian injunction to become a self through choice (though it superficially resembles it). Nietzsche does not posit a “true self” waiting to be actualized. Rather, he invites a creative relationship with one’s own existence—not discovering what you are but making what you are through style, through affirmation, through the revaluation of values.

“To ‘give style’ to one’s character—a great and rare art! It is practiced by those who survey all the strengths and weaknesses of their nature and then fit them into an artistic plan until every one of them appears as art and reason and even weakness delights the eye.”

— The Gay Science, Section 290

This is self-creation, not self-knowledge. You do not find your true self; you compose it. You do not confess your hidden desires; you aestheticize your contradictions into a coherent work.

Against the Depths

Nietzsche explicitly mocks the cult of interiority:

“Our treasure lies in the beehives of our knowledge. We are perpetually on the way thither, being by nature winged insects and honey-gatherers of the spirit; there is one thing alone that lies close to our heart—to ‘bring something home.’ As for the rest of life, the so-called ‘experiences’—who of us has enough seriousness for them? Or enough time?”

— On the Genealogy of Morals, Preface, Section 1

The “inner life” that the Christian examines, the Buddhist observes, and the therapist probes—Nietzsche treats as a distraction. What matters is not what you find inside but what you create, what you affirm, what you build with the materials you have.

“Man would rather will nothingness than not will.”

— On the Genealogy of Morals, Essay III, final section

The danger is not that we have hidden depths that need excavating; the danger is that we use the project of self-knowledge to avoid the more difficult task of self-creation.

Part III: Indigenous Relationality—The Self Out There

A Different Location

The previous traditions—Eastern and Western—disagree about what the self is and how to know it, but they largely agree on where it is: inside, whether as rational agent, desiring will, aggregates, witness, or ground. Indigenous philosophies across many cultures challenge this localization.

The self is not inside you. It is constituted by your relationships—with land, ancestors, community, and more-than-human beings. “Who am I?” is answered by “whose am I?”

I will draw primarily on scholarship that synthesizes Indigenous perspectives, acknowledging that “Indigenous philosophy” is not monolithic—there are hundreds of distinct traditions. But certain patterns recur widely enough to constitute a genuine alternative paradigm.

Relational Ontology

Many Indigenous philosophies are characterized by what scholars call “relational ontology”—the view that beings are constituted by their relationships rather than existing as independent substances:

“The Native worldview is fundamentally different from the Western because the Native worldview is based on relationships... Relationships are the basis of all life in the Native worldview. Individuals do not exist in isolation; they exist in relationship.”

— Vine Deloria Jr., Spirit and Reason (1999)

Vine Deloria Jr. (Standing Rock Sioux) was one of the most influential Native American intellectuals of the twentieth century. His work consistently emphasizes that the Western question “what is this thing in itself?” makes less sense than “what is this thing in relation to?”

Applied to the self: you are not an isolated individual who then enters into relationships. You are your relationships. The question “who am I?” cannot be answered by introspection because the answer is not inside you—it is in your place in a web of kinship.

Land as Identity

In many Indigenous traditions, identity is inseparable from land—not as property but as relation:

“We are the land... that is the fundamental idea embedded in Native American life: the Earth is the mind of the people as we are the mind of the earth.”

— Paula Gunn Allen (Laguna Pueblo), The Sacred Hoop (1986)

This is not metaphor. The land is literally constitutive of who you are. When Indigenous peoples speak of “belonging to the land” (rather than the land belonging to them), they express an ontology in which identity is placed, located, rooted in specific geography.

“For Aboriginal Australians, the Dreaming is the source of identity. People are not primarily individuals but expressions of particular ancestral beings associated with specific places. To know who you are is to know your Dreaming—which is to know your country, your ancestral beings, your ceremonies, and your kin.”

— Deborah Bird Rose, Nourishing Terrains (1996), paraphrased

Self-knowledge here means knowing your place—literally. You do not excavate hidden desires; you learn the stories of your country, the songs that belong to your Dreaming track, the ceremonies that connect you to ancestors and land.

Ancestors as Present

In many African philosophical traditions, the self extends backward in time through ancestors, who remain present and active:

“I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am.”

— John Mbiti, summarizing Ubuntu philosophy in African Religions and Philosophy (1969)

Ubuntu—a Nguni Bantu term often translated as “I am because you are”—expresses a relational conception of personhood. The self is not the isolated individual of Western philosophy but a node in networks of relationship.

Ancestors are not merely dead people to be remembered; they are present participants in community life:

“The African concept of the person maintains that the living and the dead are bound together in a community that stretches from the present back through time. The ancestors remain present, accessible, and influential. Identity is thus not confined to the individual body but extends through relationships with the living and the dead.”

— Kwame Gyekye, An Essay on African Philosophical Thought (1987), paraphrased

To know yourself, you must know your ancestors—their names, their deeds, your obligations to them. This is not historical curiosity but ontological grounding. You are, in some sense, them—their continuation, their presence in the present.

Kinship with More-Than-Human Beings

Many Indigenous traditions extend kinship beyond the human:

“The Lakota believe that all living things are related, including animals, plants, and the earth itself. The phrase ‘Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ’—all my relations—is spoken in ceremony to acknowledge this kinship.”

— Traditional Lakota teaching

Robin Wall Kimmerer (Citizen Potawatomi Nation), a botanist and writer, articulates this in her influential book Braiding Sweetgrass (2013):

“In the indigenous worldview, a human being is one member of a community of beings—plants, animals, rocks, and waters are all members. The notion of an individual self separate from nature is foreign to this way of knowing.”

— Braiding Sweetgrass, paraphrased

If you are kin to the salmon, the cedar, the river—then self-knowledge must include knowledge of these relations. The question is not “what do I want?” but “what are my obligations to my relatives?” The self is not a container of desires but a position in a network of reciprocity.

Story as Identity

In many Indigenous traditions, identity is constituted by story—not autobiography in the confessional sense, but the collective stories that place you in the world:

“Stories are not entertainment. Stories are power. They reflect the deepest, the most intimate perceptions, relationships, and attitudes of a people. Stories show how the people relate to the world.”

— Leslie Marmon Silko (Laguna Pueblo), Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit (1996)

Your story is not primarily about your individual experiences (your trauma, your desires, your choices); it is about your people’s experiences, the mythic narratives that structure reality, the ancestral deeds that continue through you.

“I don’t remember a single day of my childhood when my grandfather did not tell me who I was, and who my people were, and how we came to be in this place.”

— Attributed to an Indigenous elder, widely cited

Self-knowledge here is not introspection but reception of tradition. You learn who you are by being told—by elders, by ceremony, by the stories that were told before you were born and will be told after you die.

The Critique of Individualism

From these perspectives, the entire Western project of self-knowledge—Greek, Christian, modern therapeutic—looks pathological:

“The Western self is an autonomous, bounded individual who exists prior to and independent of relationships. This is not a universal human experience; it is a cultural artifact—and a rather recent and peculiar one.”

— Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, on Amerindian perspectivism, paraphrased

The assumption that you have an interior that can be examined, a hidden truth that can be excavated, a self that exists independent of relationship—all of this presupposes a particular (and peculiar) ontology. Indigenous philosophies suggest that this ontology is not merely incomplete but mistaken.

The lonely individual examining their conscience, the patient on the therapist’s couch, the meditator watching their breath—all are operating within an individualist paradigm that other cultures never entered.

Part IV: What These Three Share

Despite their differences, Daoism, Nietzsche, and Indigenous relationality converge on certain critiques:

The Critique of Effort

Daoism explicitly criticizes effortful self-cultivation. Nietzsche criticizes the “will to truth” as another form of the will to power. Indigenous traditions emphasize receiving identity through relationship and story rather than achieving it through practice.

None of them say “work harder at knowing yourself.” All of them suggest that the very effort of self-examination may be part of the problem—either because it interferes with naturalness (Daoism), serves hidden interests (Nietzsche), or mislocates the self (Indigenous).

The Critique of Interiority

All three question the assumption that the self is “in here.”

Daoism: The self is a process of transformation continuous with the Dao; the boundaries you draw around it are artificial.

Nietzsche: The “inner” self is a grammatical fiction; what exists are forces, drives, interpretations without an interpreter.

Indigenous: The self is constituted by relations with land, ancestors, kin, and more-than-human beings; it is “out there” as much as “in here.”

The Critique of Articulation

All three are suspicious of language as the medium of self-knowledge.

Daoism: The Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao; the self that can be articulated is not the natural self.

Nietzsche: Language imposes the subject-predicate structure that creates the fiction of the self in the first place.

Indigenous: Identity is carried in story, ceremony, and relationship—not in the confessional first-person discourse of “I feel” and “I want.”

Part V: A Revised Taxonomy

We now have eleven positions, which can be grouped into three categories:

Those Who Assume a Self and Seek to Know It

Those Who Question the Self

The Deeper Question

The first group argues about what the self is and how to know it. The second group asks whether “the self” is the right frame at all.

This does not mean the second group is “right.” Perhaps the self really is an interior that can be examined. Perhaps the Daoist, Nietzschean, and Indigenous critiques are themselves limited perspectives.

But encountering these critiques changes the game. You can no longer assume that self-knowledge is obviously a good project, that interiority is obviously the right location, that articulation is obviously the right method. These are not necessities; they are options—culturally specific, historically contingent, philosophically contestable.

Part VI: Living the Questions

The Exhaustion of Introspection

Many modern people reach a point of exhaustion with self-examination. They have therapized, journaled, meditated, confessed. They know their attachment styles, their trauma responses, their Enneagram types. And yet—something remains unsatisfied.

The three perspectives in this essay offer a diagnosis: perhaps you have been looking in the wrong place, with the wrong tools, for the wrong thing.

Daoist diagnosis: You are trying too hard. The self you seek is not something achieved by effort but something revealed when effort ceases. Stop analyzing and start flowing.

Nietzschean diagnosis: You are chasing a fiction. There is no “true self” to find—only forces to deploy, materials to shape, a life to create. Stop excavating and start making.

Indigenous diagnosis: You are looking in the wrong place. The self is not inside you; it is in your relationships, your place, your people, your story. Stop introspecting and start connecting.

Practical Implications

What might it look like to take these perspectives seriously?

From Daoism: Practices that cultivate wu-wei—not adding more techniques but subtracting, not analyzing but relaxing into naturalness. Taijiquan, for instance, is not self-examination but self-forgetting-in-motion. Flow states in any domain have this quality: the self disappears into the activity.

From Nietzsche: The shift from self-discovery to self-creation. Instead of asking “what do I really want?” asking “what do I want to want? What kind of person do I want to become? How do I give style to my character?” This is closer to art than archaeology.

From Indigenous traditions: The shift from interior to relation. Instead of journaling about your feelings, learning the names of the plants around your house. Instead of examining your childhood, learning your ancestors’ stories. Instead of asking “who am I?” asking “whose am I? What place do I belong to? What are my obligations?”

The Freedom of Not Knowing

All eleven traditions in this essay series—and countless others—represent human attempts to grapple with the question of self-relation. None of them has the final word. Each illuminates something; each has blind spots.

To hold them all in mind is not confusion but freedom. You are no longer committed to a single model you never chose but inherited. You can ask: What does this situation call for? What tool fits this problem?

Sometimes you need to examine your beliefs for coherence. Sometimes you need to confess hidden motives. Sometimes you need to observe phenomena without identification. Sometimes you need to practice better conduct. Sometimes you need to discriminate between witness and witnessed. Sometimes you need to remember yourself. Sometimes you need to choose decisively. Sometimes you need to let go. Sometimes you need to stop trying. Sometimes you need to unmask your unmasking. Sometimes you need to connect with land, ancestors, and kin.

And sometimes—perhaps often—the question “how do I know myself?” is itself the obstacle, and the answer is to forget the question and live.

Coda: The Fish Trap

We return to Zhuangzi:

“The fish trap exists because of the fish. Once you’ve gotten the fish, you can forget the trap. Words exist because of meaning. Once you’ve gotten the meaning, you can forget the words. Where can I find a man who has forgotten words so I can have a word with him?”

These four essays have been fish traps—words about the self, methods for knowing, traditions for comparing. They were never the point. The point was whatever you caught, whatever shifted in your understanding, whatever freedom you gained.

Now forget the trap.

Selected Sources

Daoist Texts:

-

Dao De Jing, various translations (Addiss and Lombardo, D.C. Lau, Red Pine)

-

Zhuangzi, trans. Burton Watson

-

Liezi, trans. A.C. Graham

-

Slingerland, Edward. Trying Not to Try: Ancient China, Modern Science, and the Power of Spontaneity

Nietzsche:

-

Beyond Good and Evil, trans. Kaufmann

-

On the Genealogy of Morals, trans. Kaufmann

-

The Gay Science, trans. Kaufmann

-

Ecce Homo, trans. Kaufmann

-

Nehamas, Alexander. Nietzsche: Life as Literature

Indigenous Perspectives:

-

Deloria, Vine Jr. Spirit and Reason

-

Allen, Paula Gunn. The Sacred Hoop

-

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass

-

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit

-

Mbiti, John. African Religions and Philosophy

-

Rose, Deborah Bird. Nourishing Terrains

Comparative and Synthetic:

-

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. Cannibal Metaphysics

-

Watts, Alan. The Way of Zen (comparative East-West)

-

Cooper, David E. Convergence with Nature: A Daoist Perspective