Know Thyself: The Kingdom Within

Published 2025-12-17

-

Pt 1: Greek vs Christian

-

Pt 4: No Self

-

Pt 5: Through What?

-

Pt 6: The Kingdom Within

“The kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and people do not see it.” — Gospel of Thomas, Saying 113

“If those who lead you say to you, ‘See, the kingdom is in the sky,’ then the birds of the sky will precede you. If they say to you, ‘It is in the sea,’ then the fish will precede you. Rather, the kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you. When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living Father.” — Gospel of Thomas, Saying 3

Introduction: Which Christianity?

The previous essays treated “Christianity” as if it named a single psychology—the Augustinian model of hidden desire, self-opacity, and verbal confession. But this is historically naive. What we call “Christianity” is the product of centuries of development, and the tradition that became dominant (Paul → Augustine → Lateran IV → the confessional) represents one trajectory among several.

Before Paul theologized the cross, before Augustine discovered the opacity of the will, before the institutional church required annual confession—there was Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish teacher whose sayings circulated in oral tradition and were eventually written down in various forms. Some of these sayings suggest a psychology radically different from what Christianity became.

This essay recovers that earlier strand—not to claim we can access the “real Jesus” (a fraught scholarly project) but to show that the Christian tradition contains resources that the Augustinian model suppressed. These resources align surprisingly well with some Eastern traditions: the kingdom within, the divine spark, transformation through practice, direct access to the source.

The institutional church that Paul helped build and Augustine theologized is one Christianity. But there is another Christianity—a wisdom tradition, a way of transformation—that never entirely disappeared and that offers a different psychology of self-knowledge.

Part I: The Sayings Tradition

Jesus as Wisdom Teacher

Modern scholarship on the historical Jesus has emphasized a distinction that earlier generations blurred: the difference between Jesus as he appears in the earliest sayings traditions and the theological Christ of Paul’s letters and the later creeds.

The Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke) preserve layers of tradition. The earliest layer—what scholars call “Q” (from German Quelle, “source”) and the independent sayings collection known as the Gospel of Thomas—presents Jesus primarily as a wisdom teacher, not as a dying-and-rising savior.

“The historical Jesus was a Jewish wisdom teacher who used parables, aphorisms, and symbolic actions to point toward a way of being in the world. The cross and resurrection became central only in the theological reflection that followed his death.”

— Marcus Borg, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time (paraphrase)

This is not to diminish the theological developments—they are what Christianity became. But it is to note that the psychology implicit in the early sayings tradition differs from the psychology of Pauline and Augustinian Christianity.

The Kingdom as Present Reality

The central theme of Jesus’s teaching in the Synoptics is the “kingdom of God” (or “kingdom of heaven” in Matthew). But what does this mean?

Later Christianity interpreted the kingdom primarily as a future event—the end of the world, the Second Coming, the final judgment. This eschatological reading supports an institutional church: the church manages salvation between Jesus’s departure and his return.

But many of Jesus’s sayings suggest the kingdom is already present—not a future event but a present reality that most people fail to perceive:

“The kingdom of God is not coming with signs to be observed; nor will they say, ‘Lo, here it is!’ or ‘There!’ for behold, the kingdom of God is in your midst.”

— Luke 17:20-21 (RSV)

The Greek phrase entos hymōn is ambiguous: it can mean “among you” (the kingdom is present in the community) or “within you” (the kingdom is inside each person). The institutional church preferred the first reading; the mystical tradition preferred the second.

The Gospel of Thomas, which lacks any narrative framework and presents only sayings, consistently emphasizes the present, interior kingdom:

“Jesus said, ‘If those who lead you say to you, “See, the kingdom is in the sky,” then the birds of the sky will precede you. If they say to you, “It is in the sea,” then the fish will precede you. Rather, the kingdom is inside of you, and it is outside of you.’”

— Gospel of Thomas, Saying 3

“His disciples said to him, ‘When will the kingdom come?’ Jesus said, ‘It will not come by waiting for it. It will not be a matter of saying “here it is” or “there it is.” Rather, the kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and people do not see it.’”

— Gospel of Thomas, Saying 113

This is not the psychology of sin and confession. It is the psychology of blindness and seeing. The problem is not that you have hidden desires that must be excavated; the problem is that you fail to perceive what is already present. The solution is not confession but awakening.

Know Thyself—Christian Version

The Gospel of Thomas explicitly links the kingdom to self-knowledge:

“When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living Father. But if you will not know yourselves, you dwell in poverty and it is you who are that poverty.”

— Gospel of Thomas, Saying 3

This is “know thyself”—but in a register very different from Augustine. Augustine’s self-knowledge means discovering your hidden sinfulness, your opacity to yourself. Thomas’s self-knowledge means recognizing your divine origin, your identity as a “son of the living Father.”

“Jesus said, ‘I am the light that is over all things. I am all: from me all came forth, and to me all attained. Split a piece of wood; I am there. Lift up the stone, and you will find me there.’”

— Gospel of Thomas, Saying 77

The divine is not far off, mediated by institution and sacrament. It is immediate, present, everywhere—even in wood and stone. Self-knowledge is recognizing this presence, including the presence within oneself.

“Jesus said, ‘If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you. If you do not bring forth what is within you, what you do not bring forth will destroy you.’”

— Gospel of Thomas, Saying 70

There is something within you that must be “brought forth”—but this is not the hidden sin that confession extracts. It is the divine spark, the image of God, the kingdom within. The practice is not confession but expression, not excavation of guilt but manifestation of light.

Part II: The Divine Spark

Image and Likeness

The Hebrew Bible begins with a statement that later traditions developed in very different directions:

“Then God said, ‘Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness’... So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them.”

— Genesis 1:26-27 (NRSV)

What does it mean to be created in God’s image (tselem) and likeness (demut)? The mainstream Western tradition, especially after Augustine, emphasized the Fall: the image was damaged, obscured, nearly destroyed by sin. Redemption means restoring a broken image through grace mediated by the church.

But another reading—present in Eastern Orthodoxy and in various mystical traditions—emphasizes the indelibility of the image. The divine spark cannot be extinguished. It may be obscured, forgotten, covered over—but it remains. Self-knowledge means uncovering what was always there, not repairing what was broken.

Theosis: Eastern Orthodox Alternative

Eastern Orthodox Christianity developed differently from Western Christianity. While the West emphasized sin, guilt, and forensic justification (being declared righteous), the East emphasized theosis—divinization, becoming god-like, participating in the divine nature.

“God became human so that humans might become god.”

— Athanasius, On the Incarnation (4th century)

This is not a minor theme; it is central to Orthodox spirituality. The goal of the Christian life is not merely forgiveness but transformation—becoming by grace what God is by nature.

“The Word of God became man, that you may learn from man how man becomes god.”

— Clement of Alexandria, Exhortation to the Heathen (2nd century)

The psychology here is closer to Hindu recognition (you are already Brahman; realize it) than to Augustinian confession (you are fallen; confess and be absolved). The divine image is not lost but veiled. Spiritual practice removes the veil.

Gregory of Nyssa (4th century) described the soul as a mirror:

“The soul is like a mirror. When it is properly cleaned and purified, it reflects the image of God. But when it is covered with the rust of sin, it cannot reflect that divine image. Yet the image is not destroyed—only obscured.”

— Gregory of Nyssa, On the Soul and Resurrection (paraphrase)

This is not excavating hidden sin; it is polishing a mirror to reveal what was always there. The practice is purification rather than confession—though confession may be part of purification, it is not the central mechanism.

Gnostic Christianity

The Gnostic movements of the 2nd and 3rd centuries pushed the “divine spark” idea further—sometimes in directions the church condemned as heretical. But the Gnostics preserved something that mainstream Christianity suppressed: the radical immanence of the divine in the human soul.

The Gospel of Philip (a Gnostic text from the Nag Hammadi library):

“You saw the Spirit, you became Spirit. You saw Christ, you became Christ. You saw the Father, you shall become Father... You see yourself, and what you see you shall become.”

— Gospel of Philip, Saying 44

This is transformation through seeing—not confession of hidden guilt but recognition of hidden divinity. The problem is not sin but ignorance (agnoia); the solution is not absolution but gnosis (knowledge, recognition).

The mainstream church rejected Gnosticism for many reasons—some theological, some political. But in doing so, it suppressed a psychology of immanent divinity in favor of a psychology of transcendent deity mediated by institution. The divine spark became heretical; the fallen will became orthodox.

Part III: The Way vs. The Institution

Following the Way

The earliest Christians did not call themselves “Christians.” They were followers of “the Way” (hē hodos):

“Meanwhile Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord, went to the high priest and asked him for letters to the synagogues at Damascus, so that if he found any who belonged to the Way, men or women, he might bring them bound to Jerusalem.”

— Acts 9:1-2

“The Way” suggests practice, path, manner of life—not assent to doctrine or membership in institution. Jesus is presented in the Gospels as teaching a way of living: how to pray, how to treat others, how to relate to wealth and power, how to trust in providence.

“Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it.”

— Matthew 7:13-14

The path metaphor is universal—the Dao, the Buddhist Eightfold Path, the Hindu mārga. It implies that transformation comes through practice, through walking a path, through gradual cultivation. This is very different from the crisis-and-resolution pattern of confession: sin, guilt, confession, absolution, repeat.

Paul’s Innovation

Paul never met the earthly Jesus. His encounter was visionary—the risen Christ on the road to Damascus. His letters, written before the Gospels, interpret Jesus’s significance primarily through his death and resurrection:

“For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures.”

— 1 Corinthians 15:3-4

This is the kerygma—the proclamation of Christ’s saving death. It shifts attention from Jesus’s teaching to Jesus’s death, from following a path to believing in an event.

Paul also developed the theology of universal sin:

“Therefore, just as sin came into the world through one man, and death came through sin, and so death spread to all because all have sinned...”

— Romans 5:12

This is the seed of Augustine’s doctrine of original sin. If all are sinners through Adam’s fall, then all need redemption through Christ’s death. The church administers this redemption through sacraments. The psychology shifts from “walk the path, awaken to the kingdom” to “you are fallen, believe and be saved.”

This is not to vilify Paul—his letters are profound and have nourished countless lives. But it is to note a shift in psychology: from practice to belief, from Way to institution, from kingdom within to salvation from without.

What Was Lost

When Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire (4th century), the institutional trajectory accelerated. The church needed clear doctrine, defined membership, mechanisms of discipline. Confession, penance, and absolution became technologies of pastoral control.

Augustine’s personal psychology—his tortured relationship with desire, his sense of his own opacity—became the template for Western Christian selfhood. The Confessions is a masterpiece, but it is also an artifact of a particular personality and historical moment. It need not define all Christian psychology.

What was lost (or marginalized) in this development:

-

The kingdom as present reality rather than future event

-

Self-knowledge as recognition of divine image rather than excavation of sin

-

Transformation through practice rather than crisis-and-absolution

-

Direct access to the divine rather than institutional mediation

-

The divine spark that cannot be extinguished

These themes did not disappear entirely. They survived in monasticism, in mysticism (Eckhart, the Rhineland mystics, the author of The Cloud of Unknowing), in Eastern Orthodoxy, in Quaker “inner light” theology, in various renewal movements. But they became minority reports within a tradition dominated by the Pauline-Augustinian synthesis.

Part IV: The Sermon on the Mount

Practice, Not Belief

The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7) is the longest continuous teaching attributed to Jesus in the Synoptic Gospels. It is remarkably light on theology and heavy on practice:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘An eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth.’ But I say to you, Do not resist an evildoer. But if anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn the other also.”

— Matthew 5:38-39

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven.”

— Matthew 5:43-45

This is ethics, not eschatology. It is about how to live, not what to believe about cosmic events. The psychology is transformative: by practicing these teachings, you become a child of the Father, you become the kind of person who inhabits the kingdom.

The Sermon culminates with the parable of the wise and foolish builders:

“Everyone then who hears these words of mine and acts on them will be like a wise man who built his house on rock... And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not act on them will be like a foolish man who built his house on sand.”

— Matthew 7:24-26

Acting on the words. Not believing doctrines, not confessing sins—doing what Jesus taught. This is closer to Confucian practice or Buddhist discipline than to the Augustinian confession model.

The Lord’s Prayer

The prayer Jesus taught is notably absent of sin-focused content in its original form:

“Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come. Your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And do not bring us to the time of trial, but rescue us from the evil one.”

— Matthew 6:9-13

“Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors”—this is reciprocal forgiveness, tied to action (forgiving others), not the unilateral confession-absolution model of later Christianity. It is relational and ethical, not introspective and psychological.

The prayer is also brief and simple—a far cry from the elaborate examination of conscience that later confession would require. Jesus explicitly criticizes lengthy prayer:

“When you are praying, do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do; for they think that they will be heard because of their many words.”

— Matthew 6:7

The Interior Focus

Yet the Sermon on the Mount does have an interior dimension—not of sin-excavation but of sincerity and purity of heart:

“Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.”

— Matthew 5:8

Purity of heart—not complexity of confession. Seeing God—not endless analysis of motive. This beatitude suggests that the goal is simplification, becoming single-hearted, not archaeological exploration of one’s hidden depths.

Jesus criticizes hypocrisy—the gap between outer performance and inner reality:

“Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them... When you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be done in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.”

— Matthew 6:1-4

The Father “sees in secret”—there is an interior dimension that matters. But the prescription is not to excavate this interior through confession; it is to align outer and inner, to become whole rather than divided.

Part V: Two Christianities

The Contrast

We can now sketch the two psychologies:

Pauline-Augustinian Christianity:

-

Problem: Original sin, universal fallenness, hidden concupiscence

-

Self: Opaque to itself, self-deceived, needing external grace

-

Practice: Confession, examination of conscience, institutional mediation

-

Goal: Absolution, forgiveness, salvation after death

-

Emphasis: Belief in saving events (cross, resurrection)

Wisdom-Tradition Christianity:

-

Problem: Blindness, ignorance, failure to perceive the kingdom

-

Self: Bears divine image, contains divine spark, capable of transformation

-

Practice: Following the Way, ethical action, contemplation, awakening

-

Goal: Seeing God, entering the kingdom (now), becoming children of the Father

-

Emphasis: Practice of teachings, transformation of life

These are not simply “early” vs. “late”—both strands appear in the earliest texts. But the Pauline-Augustinian model became institutionally dominant, while the wisdom tradition survived in mystical and monastic margins.

Connections to Other Traditions

The wisdom-tradition Christianity connects naturally to traditions we’ve already examined:

Hindu (Advaita): The divine image that cannot be destroyed resembles the ātman that is always already Brahman. Self-knowledge is recognition, not excavation.

Buddhist: “The kingdom is spread out upon the earth and people do not see it” resembles the Buddha’s teaching that liberation is available now, if we stop clinging. The problem is blindness, not sin.

Daoist: The simplicity of the Sermon on the Mount, the critique of “heaping up empty phrases,” the emphasis on naturalness and sincerity—these resonate with Daoist sensibility.

Gurdjieff: “If you bring forth what is within you, what you bring forth will save you” could almost be a Gurdjieff teaching: there is something latent that must be actualized through work.

Eckhart: The kingdom within, the divine spark, the ground where soul and God are one—Eckhart recovered these themes from within the Christian tradition, drawing on sources the mainstream church had marginalized.

The Recovery

Various movements have attempted to recover wisdom-tradition Christianity:

-

Eastern Orthodoxy: Never adopted Augustine’s doctrine of original sin in its Western form; preserved theosis as central.

-

Quakerism: The “inner light” present in every person; silent worship rather than priestly mediation.

-

Liberal Protestantism: The “historical Jesus” as ethical teacher; the kingdom as present social reality.

-

Contemplative Christianity: Thomas Merton, Richard Rohr, Cynthia Bourgeault—recovering contemplative practice and the mystical tradition.

These recovery projects are not about rejecting Paul or Augustine wholesale. It is about recognizing that the tradition is richer than any single strand, and that the Augustinian confession model is not the only Christian psychology.

Part VI: Implications

A Different Practice

If the wisdom-tradition psychology is valid, what practices would it suggest?

Contemplation over confession: Silent attention to the divine presence within, rather than verbal examination of hidden sins. The practices of lectio divina, centering prayer, and Christian meditation fit this model.

Practice over belief: The emphasis shifts from assenting to correct doctrine to living correctly. “Everyone who hears these words of mine and acts on them...” The Sermon on the Mount becomes a manual for transformation.

Recognition over excavation: Self-knowledge means recognizing the divine image, not digging for hidden guilt. “When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living Father.”

Simplification over complexity: The “pure in heart” will see God. The goal is not more sophisticated self-analysis but less—a single eye, a whole heart, the simplicity that sees through multiplicity to unity.

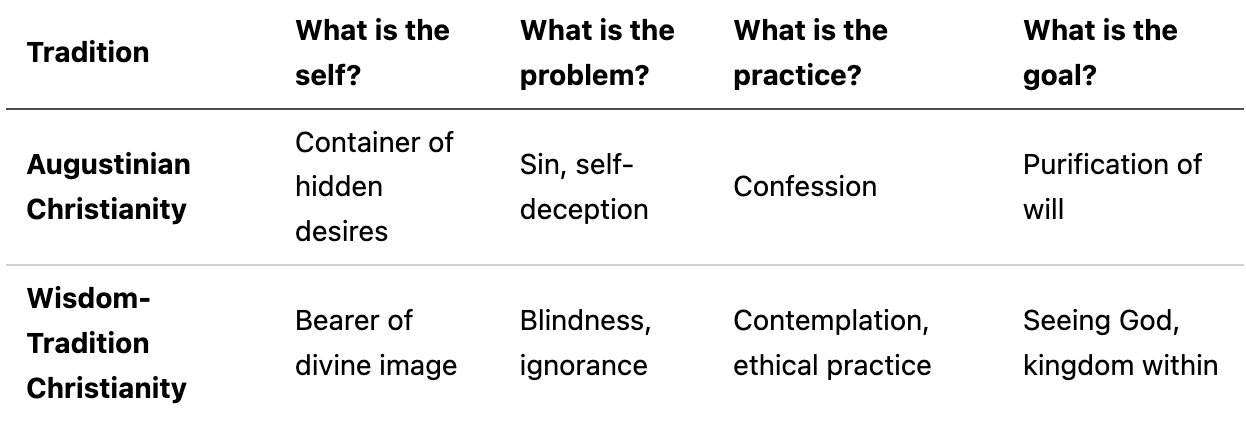

Integration with the Taxonomy

Adding wisdom-tradition Christianity to our taxonomy:

These are both “Christian”—but they are different psychologies, with different implications for how one lives.

The Perennial Philosophy

The wisdom-tradition Christianity connects to what Aldous Huxley called the “perennial philosophy”—the claim that beneath the surface differences of world religions lies a common core:

“The divine Ground of all existence is a spiritual Absolute, ineffable in terms of discursive thought, but susceptible of being directly experienced and realized by the human being. This Absolute is the inner essence and ultimate ground of the human soul... The final end of human life is to discover this eternal Self and so to come to unitive knowledge of the divine Ground.”

— Aldous Huxley, The Perennial Philosophy (1945), paraphrase

Whether the perennial philosophy thesis is literally true, it points to a real family resemblance among mystical and wisdom traditions across cultures. The kingdom within, the divine spark, the ātman-Brahman identity, the Buddha-nature—these are variations on a theme.

The institutional religions, by contrast, often diverge more sharply—because institutions need boundaries, doctrines, mechanisms of control. The Pauline-Augustinian Christianity that became dominant is in some sense the “institutional” Christianity, while the wisdom tradition represents the “perennial” Christianity that resonates with parallel discoveries in other traditions.

Conclusion: Recovering the Kingdom

We began these essays with Augustine’s Confessions—the discovery that the self is opaque to itself, that hidden desires must be excavated through speech, that the institution mediates between the fallen soul and the distant God.

But this is not the only Christianity. Beneath the institutional accretions, there is a wisdom tradition—preserved in the sayings of Jesus, in the Gospel of Thomas, in Eastern Orthodox theosis, in the mystical currents that never quite disappeared.

This tradition teaches that the kingdom is within, that the divine spark cannot be extinguished, that self-knowledge means recognizing your true nature as image of God, that transformation comes through practice, that seeing God is possible now.

“The kingdom of the Father is spread out upon the earth, and people do not see it.”

The problem is not hidden sin but hidden treasure. The practice is not confession but contemplation. The goal is not absolution but awakening.

This is Christianity too—perhaps the older Christianity, certainly a Christianity that speaks across traditions to Buddhist, Hindu, Daoist, and Indigenous sensibilities. It has never entirely disappeared. It waits to be recovered.

“When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known.”

Selected Sources

Primary Texts:

-

Gospel of Thomas, trans. Lambdin (in The Nag Hammadi Library, ed. Robinson)

-

Gospel of Philip, trans. Isenberg (in The Nag Hammadi Library)

-

New Testament (NRSV), especially Matthew 5-7, Luke 17, John 14-17

-

Athanasius, On the Incarnation

-

Gregory of Nyssa, On the Soul and Resurrection

-

Clement of Alexandria, Exhortation to the Heathen

Historical Jesus Scholarship:

-

Borg, Marcus. Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time

-

Crossan, John Dominic. The Historical Jesus: The Life of a Mediterranean Jewish Peasant

-

Funk, Robert, and Roy Hoover (eds.). The Five Gospels: What Did Jesus Really Say?

-

Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels

-

Pagels, Elaine. Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas

Eastern Orthodox Theology:

-

Lossky, Vladimir. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church

-

Ware, Kallistos. The Orthodox Way

-

Meyendorff, John. Byzantine Theology

Contemporary Recovery:

-

Bourgeault, Cynthia. The Wisdom Jesus

-

Rohr, Richard. The Universal Christ

-

Merton, Thomas. New Seeds of Contemplation

-

Huxley, Aldous. The Perennial Philosophy

On the Development of Doctrine:

-

Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Christian Tradition (5 vols.)

-

Ehrman, Bart. Lost Christianities

-

MacCulloch, Diarmaid. Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years