Know Thyself: Through What?

Published 2025-12-17

-

Pt 1: Greek vs Christian

-

Pt 4: No Self

-

Pt 5: Through What?

-

Pt 6: The Kingdom Within

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” — Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus 7

“Language is the house of Being. In its home human beings dwell.” — Heidegger, “Letter on Humanism”

Introduction: The Medium Becomes the Problem

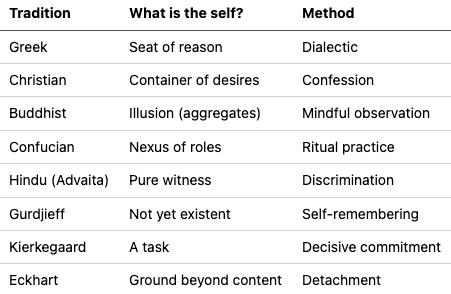

The previous essays examined eleven psychologies of self-knowledge, from Greek dialectic to Indigenous relationality. Each tradition assumes, in different ways, that language can serve the project of self-understanding—whether through Socratic dialogue, Christian confession, Buddhist phenomenological description, or Confucian learning.

Two twentieth-century thinkers radically complicate this assumption. Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) and Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) both place language at the center of philosophical inquiry—but in doing so, they reveal that the medium we use to know ourselves may systematically distort or even create the “self” we think we’re knowing.

Wittgenstein asks: Can we even coherently speak about inner states? Do the words we use to describe our desires, beliefs, and feelings actually refer to private objects that introspection discovers?

Heidegger asks: Does the very structure of our language—subject, predicate, object—impose a framework that conceals more primordial ways of being? Is “the self” a construction of grammar rather than a discovery of inquiry?

Both thinkers suggest that the self-knowledge project may be confused at its root—not because the self is hard to know (Augustine), or illusory (Buddhism), or not yet built (Gurdjieff), but because the linguistic tools we bring to the task are fundamentally unsuited to it.

Part I: Wittgenstein—The Beetle in the Box

The Early Wittgenstein: Drawing the Limits

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) attempts to draw the limits of meaningful language. Its central claim: language pictures facts; what cannot be pictured cannot be meaningfully said.

“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”

— Tractatus 5.6

This has immediate implications for self-knowledge. The “self” or “subject” cannot appear within the world it represents:

“The subject does not belong to the world: rather, it is a limit of the world.”

— Tractatus 5.632

“Where in the world is a metaphysical subject to be found? You will say that this is exactly like the case of the eye and the visual field. But really you do not see the eye. And nothing in the visual field allows you to infer that it is seen by an eye.”

— Tractatus 5.633

The self is not an object within experience but the limit of experience—like the eye that sees but cannot see itself. This echoes the Hindu notion of the witness (sākṣin) who observes but cannot be observed. But Wittgenstein draws a more radical conclusion: if the self cannot be pictured, then talk about the self is not meaningful in the way we assume.

The Tractatus ends famously:

“Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

— Tractatus 7

This is not merely an admission of ignorance but a logical constraint. The deepest things—the self, ethics, the meaning of life—lie beyond what language can capture. We can gesture toward them, but we cannot say them.

The Later Wittgenstein: Meaning as Use

Wittgenstein later came to reject much of the Tractatus, but not its suspicion of language. The Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously, 1953) attacks the picture theory of meaning—the idea that words get their meaning by corresponding to objects—and replaces it with the slogan: meaning is use.

“For a large class of cases—though not for all—in which we employ the word ‘meaning’ it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”

— Philosophical Investigations §43

This transforms the question of self-knowledge. If words like “pain,” “desire,” “belief,” and “intention” get their meaning from how they are used in public language-games, then what happens to the private inner realm that introspection supposedly discovers?

The Private Language Argument

Wittgenstein’s most devastating contribution to the psychology of self-knowledge is the private language argument. It attacks the assumption—shared by Augustine, Descartes, and modern psychology—that we have privileged access to inner states that we then report through language.

Imagine trying to create a language for purely private sensations—sensations that only you can experience and that have no external criteria for their application:

“Let us imagine the following case. I want to keep a diary about the recurrence of a certain sensation. To this end I associate it with the sign ‘S’ and write this sign in a calendar for every day on which I have the sensation.—I will remark first of all that a definition of the sign cannot be formulated.—But still I can give myself a kind of ostensive definition.—How? Can I point to the sensation? Not in the ordinary sense. But I speak, or write the sign down, and at the same time I concentrate my attention on the sensation—and so, as it were, point to it inwardly.—But what is this ceremony for? For that is all it seems to be! A definition surely serves to establish the meaning of a sign.—Well, that is done precisely by the concentrating of my attention; for in this way I impress on myself the connexion between the sign and the sensation.—But ‘I impress it on myself’ can only mean: this process brings it about that I remember the connexion right in the future. But in the present case I have no criterion of correctness.”

— Philosophical Investigations §258

The key phrase: “I have no criterion of correctness.” If there is no way to distinguish between actually remembering the sensation correctly and merely thinking you remember it correctly, then the language lacks the normativity that makes it language at all. You could be using ‘S’ consistently or inconsistently, and there would be no fact of the matter.

This undermines the entire introspective project. If I cannot establish a private language for my own sensations, then the language I use to describe my inner life must be public language—language whose meaning is determined by shared criteria, external behavior, and social practice.

The Beetle in the Box

Wittgenstein offers a vivid image:

“Suppose everyone had a box with something in it: we call it a ‘beetle.’ No one can look into anyone else’s box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.—Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing.—But suppose the word ‘beetle’ had a use in these people’s language?—If so it would not be used as the name of a thing. The thing in the box has no place in the language-game at all; not even as a something: for the box might even be empty.—No, one can ‘divide through’ by the thing in the box; it cancels out, whatever it is.”

— Philosophical Investigations §293

The “beetle” is the private sensation—pain, desire, intention—that we think we’re reporting when we talk about our inner lives. Wittgenstein’s point: even if there is something in the box, it plays no role in the meaning of the word. The word “pain” gets its meaning from how it’s used in public contexts—in pain-behavior, in circumstances of injury, in expressions and responses—not from some private object that introspection discovers.

The Implications for Self-Knowledge

If Wittgenstein is right, the Christian confession model is deeply confused. The penitent who searches for hidden desires and reports them to the priest is not accessing a private inner realm; they are participating in a language-game whose meaning is constituted by the practice of confession itself. The “hidden desire” is not discovered and then reported; it is constituted by the practice of reporting.

This does not mean inner states are unreal. It means that what we call “inner states” are not private objects that language merely labels. They are partly constituted by the language we use to describe them and the social practices in which that language is embedded.

“An ‘inner process’ stands in need of outward criteria.”

— Philosophical Investigations §580

The Augustinian who says “I do not know my own heart” is not reporting a discovery about the hiddenness of inner states. They are using a form of words whose meaning comes from the Christian practice of confession, humility, and spiritual direction. The “hidden heart” is a product of the language-game, not an object the language-game describes.

Grammar and the Self

Wittgenstein’s later method involves attending to the “grammar” of our concepts—not grammar in the syntactic sense, but the rules that govern how words can meaningfully be used:

“Grammar tells what kind of object anything is.”

— Philosophical Investigations §373

The grammar of psychological concepts—belief, desire, intention, memory—is not the grammar of physical objects. We are misled by surface similarities:

“How does the philosophical problem about mental processes and states and about behaviourism arise?—The first step is the one that altogether escapes notice. We talk of processes and states and leave their nature undecided. Sometime perhaps we shall know more about them—we think. But that is just what commits us to a particular way of looking at the matter. For we have a definite concept of what it means to learn to know a process better. (The decisive movement in the conjuring trick has been made, and it was the very one that we thought quite innocent.)”

— Philosophical Investigations §308

By talking about mental “states” and “processes,” we import a model from the physical world—as if beliefs and desires were objects located somewhere, waiting to be discovered. But the grammar of psychological concepts does not work that way. To ask “where is my desire?” or “what is my intention made of?” is to misunderstand the kind of concept we’re dealing with.

The Therapeutic Task

Wittgenstein saw philosophy not as a doctrine but as a therapy—a way of dissolving confusions rather than solving problems:

“Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

— Philosophical Investigations §109

“What is your aim in philosophy?—To show the fly the way out of the fly-bottle.”

— Philosophical Investigations §309

The self-knowledge project, in many of its forms, may be a fly-bottle—a trap we create for ourselves through linguistic confusion. We posit an inner realm of private objects, then devise practices for accessing them, then worry about whether we’ve accessed them correctly. The whole apparatus may be a confusion generated by misunderstanding how our language works.

This is not nihilism. Wittgenstein is not saying there are no beliefs, desires, or intentions. He is saying that these concepts function differently than we assume when we treat self-knowledge as a kind of inner perception. The therapy is not to stop talking about the mind but to stop being confused about what we’re doing when we talk about it.

Part II: Heidegger—The House of Being

The Question of Being

Where Wittgenstein dissolves philosophical problems into linguistic therapy, Heidegger seeks to retrieve a question he believes has been forgotten: the question of Being (Sein).

“The question of Being has today been forgotten... It is said that ‘Being’ is the most universal and emptiest of concepts. As such it resists every attempt at definition.”

— Being and Time (1927), Introduction (trans. Macquarrie and Robinson)

For Heidegger, the Western philosophical tradition—from Plato onward—has focused on beings (entities, things) while forgetting to ask about Being itself: what it means for something to be. This “forgetting of Being” (Seinsvergessenheit) shapes everything, including how we understand the self.

Dasein, Not Subject

Heidegger replaces the traditional concept of “self” or “subject” with Dasein—literally “being-there” or “being-here.” Dasein is not a thing with properties but a way of existing:

“Dasein is an entity which does not just occur among other entities. Rather it is ontically distinguished by the fact that, in its very Being, that Being is an issue for it.”

— Being and Time §4

The key phrase: “Being is an issue for it.” Dasein is not an object to be known but an existence to be lived—an existence that is always already concerned with its own being. You do not first exist and then ask about yourself; the asking is part of how you exist.

This reframes self-knowledge entirely. The Cartesian model—a subject inspecting its own contents—presupposes what Heidegger calls the “subject-object split”: a mind “in here” looking at a world (or itself) “out there.” But Dasein is always already in-the-world, not as a container in a larger container, but as a way of being that cannot be separated from its world:

“Being-in-the-world is a unitary phenomenon. This primary datum must be seen as a whole.”

— Being and Time §12

Thrownness and Projection

Dasein finds itself thrown (geworfen) into a situation it did not choose—a body, a culture, a language, a historical moment:

“This characteristic of Dasein’s Being—this ‘that it is’—is veiled in its ‘whence’ and ‘whither,’ yet disclosed in itself all the more unveiledly; we call it the ‘thrownness’ of this entity into its ‘there.’”

— Being and Time §29

You did not choose to exist, to speak English, to be born in this century, to have this body. You find yourself already here, already involved, already shaped by factors beyond your control. This is not a limitation to be overcome but the condition of all existence.

At the same time, Dasein projects itself toward possibilities—it is always ahead of itself, oriented toward a future:

“Dasein is constantly ‘more’ than it factually is... It is existentially that which, in its potentiality-for-Being, it is not yet.”

— Being and Time §145

Self-knowledge, then, is not the discovery of a fixed essence but the navigation of thrownness and projection—the tension between what you find yourself as and what you are becoming.

Das Man: The They-Self

Heidegger’s analysis of everyday existence reveals that we mostly do not exist as authentic individuals but as das Man—”the They” or “the One”:

“We take pleasure and enjoy ourselves as they take pleasure; we read, see, and judge about literature and art as they see and judge; likewise we shrink back from the ‘great mass’ as they shrink back; we find ‘shocking’ what they find shocking. The ‘they,’ which is nothing definite, and which all are, though not as the sum, prescribes the kind of Being of everydayness.”

— Being and Time §27

The They is not a specific group but the anonymous public norms that govern behavior. We do what “one does,” think what “one thinks,” pursue what “one pursues.” The self that operates in this mode is the they-self (Man-selbst)—not a fake self exactly, but a self that has not taken ownership of its existence.

“Proximally, it is not ‘I’ in the sense of my own Self, that ‘am,’ but rather the Others... Proximally Dasein is ‘they,’ and for the most part it remains so.”

— Being and Time §27

This echoes Gurdjieff: most people live mechanically, without self-possession. But Heidegger’s point is linguistic and ontological, not just psychological. The very language we use comes from the They. When we introspect and report what we find, we are using concepts, categories, and evaluations that are not originally our own. “Self-knowledge” in everyday mode is largely an echo of public opinion.

Authenticity and Resoluteness

Is there an alternative? Heidegger calls it Eigentlichkeit—authenticity, ownedness. Authentic existence means taking over one’s thrownness, owning one’s possibilities, existing as oneself rather than as the They:

“Authentic Being-one’s-Self does not rest upon an exceptional condition of the subject, a condition that has been detached from the ‘they’; it is rather an existentiell modification of the ‘they’—of the ‘they’ as an essential existentiale.”

— Being and Time §27

Authenticity is not escaping the They (that would be impossible—we always speak a public language, inhabit a shared world) but modifying how we relate to it. We take up what we have been thrown into as our own, rather than merely drifting with the current.

The key to this modification is confronting one’s mortality. Heidegger calls it Being-toward-death:

“Death is a possibility-of-Being which Dasein itself has to take over in every case. With death, Dasein stands before itself in its ownmost potentiality-for-Being... Death is the possibility of the absolute impossibility of Dasein.”

— Being and Time §50

“Anticipation reveals to Dasein its lostness in the they-self, and brings it face to face with the possibility of being itself... in an impassioned freedom towards death—a freedom which has been released from the Illusions of the ‘they,’ and which is factical, certain of itself, and anxious.”

— Being and Time §53

This resembles Kierkegaard: the self is not discovered but achieved, through a confrontation with existence that the They always evades. But Heidegger frames it ontologically rather than religiously. Death is not punishment for sin or gateway to eternity; it is the structure that individualizes Dasein, makes it irreducibly mine.

Language as the House of Being

In Heidegger’s later work, language moves to the center. The famous phrase:

“Language is the house of Being. In its home human beings dwell. Those who think and those who create with words are the guardians of this home.”

— “Letter on Humanism” (1947), trans. Krell

This is not the view that language is a tool we use to express pre-existing thoughts. Language is what opens up a world in the first place. Before language, there are no “things” in the human sense—no chairs, no mountains, no selves. Language lets beings appear as what they are.

“Language speaks, not man. Man only speaks when he fatefully answers to language.”

— “... Poetically Man Dwells...” (1951)

This inverts the common-sense view. We think we speak language; Heidegger says language speaks us. The words we inherit shape what can appear, what can be thought, what can be experienced. Self-knowledge is not a subject using language to describe itself; it is language bringing a self into appearance.

The Danger of Technology

Heidegger sees modern technology—and the scientific worldview that accompanies it—as a particular way of revealing beings that conceals other possibilities:

“The essence of technology is nothing technological.”

— “The Question Concerning Technology” (1954)

Modern technology treats everything as Bestand—”standing-reserve,” resources to be optimized and exploited. This includes human beings. The therapeutic self-knowledge project—with its techniques, its professionals, its metrics of mental health—may be another instance of this technological revealing: treating the self as a resource to be managed rather than an existence to be lived.

The alternative is what Heidegger calls Gelassenheit—releasement, letting-be. This word connects directly to Meister Eckhart (who invented it). In both thinkers, it names a stance of openness rather than grasping, of receiving rather than controlling.

“Releasement toward things and openness to the mystery belong together. They grant us the possibility of dwelling in the world in a totally different way.”

— “Memorial Address” (1955)

Self-knowledge under the sign of Gelassenheit would not be an excavation or an engineering project. It would be something more like listening—attending to what shows itself, without forcing it into predetermined categories.

Poetry and Disclosure

For the later Heidegger, the privileged mode of language is not science or philosophy but poetry. Poets, especially Hölderlin, open up new ways of being by saying what has never been said:

“Poetry is the establishing of being by means of the word.”

— “Hölderlin and the Essence of Poetry” (1936)

This is far from the Christian confession model. The confessing subject uses language to report hidden contents; the poet uses language to bring something into being that was not there before. Self-knowledge in the poetic mode would not be discovery but creation—not finding what was hidden but letting something new emerge.

“The poet names the holy.”

— Elucidations of Hölderlin’s Poetry

Part III: Convergences and Divergences

Both Suspect Introspection

Wittgenstein and Heidegger, despite their vast differences, converge on suspicion of the introspective project:

Wittgenstein: The “inner realm” that introspection supposedly accesses is a grammatical illusion. There is no private theater where mental events occur and are witnessed by an inner eye. Psychological language works differently than we assume.

Heidegger: The “subject” that does the introspecting is already constituted by public language and the They. What we “find” in introspection is largely an echo of das Man. Authentic self-knowledge requires a different stance—not looking inward but taking over one’s existence.

Both suggest that the self-knowledge project, as commonly conceived, is confused about the role of language. It treats language as a transparent medium for reporting inner facts. But language is not transparent. It shapes what can appear.

Different Styles

Their styles could not be more different. Wittgenstein: aphoristic, therapeutic, dissolving problems into clear seeing. Heidegger: systematic, portentous, building an elaborate ontological vocabulary. Wittgenstein would likely have found Heidegger’s language pretentious; Heidegger would likely have found Wittgenstein’s approach superficial.

But the difference runs deeper. Wittgenstein’s later philosophy is deflationary: philosophy should not produce theories but dissolve confusions. There is nothing behind the fly-bottle. Heidegger’s philosophy is inflationary: beneath our everyday understanding lies Being, which has been forgotten and must be retrieved. There is something tremendous hidden by the bustle of ordinary life.

Different Attitudes to “Depth”

Wittgenstein is suspicious of depth:

“The problems are solved, not by giving new information, but by arranging what we have always known. Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

— Philosophical Investigations §109

“Don’t think, look!”

— Philosophical Investigations §66

The therapy is to bring words back from their metaphysical use to their everyday use. The “depth” posited by philosophy—and by the Christian psychology of hidden depths—is often confusion produced by language on holiday.

Heidegger, by contrast, is a philosopher of depth par excellence. Beneath the surface of everyday life, beneath the chatter of das Man, lies the question of Being. We have forgotten something essential, and remembering it requires not dissolving confusion but retrieving what was lost.

“Making itself intelligible is suicide for philosophy.”

— Attributed to Heidegger

Yet there is a sense in which both point to something beyond articulation. Wittgenstein ends the Tractatus with silence: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Heidegger gestures toward Being, which withdraws even as it shows itself. Both are mystical in their different ways—Wittgenstein in the negative mode (there is nothing to say), Heidegger in the positive mode (there is something saying itself through us).

Connections to Other Traditions

Wittgenstein and Buddhism: The private language argument resonates with Buddhist no-self doctrine. If there are no private mental objects that words label, then the “self” that is supposed to own these objects becomes questionable. The therapeutic dissolution of philosophical problems resembles the Buddhist dissolution of suffering through seeing through clinging. Wittgenstein’s insistence on “look, don’t think” echoes the meditative injunction to observe phenomena without theorizing.

Wittgenstein and Daoism: The emphasis on naturalness, on not forcing language to do what it cannot do, on attending to practice rather than theory—these resonate with Daoist themes. The centipede who walks naturally until analysis paralyzes him could appear in Wittgenstein’s later work.

Heidegger and Eckhart: Heidegger explicitly draws on Eckhart. Gelassenheit is Eckhart’s word. The ground of the soul where God is born parallels the forgetting of Being that conceals the origin. Both thinkers point beyond subject and object, beyond the will, toward a receptivity that lets Being (or God) speak.

Heidegger and Daoism: The later Heidegger was influenced by Daoist thought. The emphasis on dwelling, on letting-be, on non-willing—these have clear parallels to wu-wei. Language speaks us; the Dao does nothing and nothing is undone.

Heidegger and Indigenous Thought: Heidegger’s critique of technology as standing-reserve, his emphasis on dwelling and place, his rejection of the rootless modern subject—these resonate with Indigenous critiques of Western individualism and placelessness. Both point toward a being-with-place that modernity has lost.

Part IV: Implications for Self-Knowledge

The Medium Is Not Transparent

Both thinkers challenge the assumption that language is a transparent medium through which we access our inner lives. The words we use to describe ourselves—belief, desire, intention, feeling, memory—do not simply label pre-existing mental objects. They are tools in language-games (Wittgenstein) or modes of disclosure within a world opened by language (Heidegger).

This means that “self-knowledge” is never pure discovery. It is always mediated by the linguistic and cultural resources available to us. The Christian who confesses is not directly accessing hidden desires; they are using a vocabulary shaped by centuries of Christian practice. The Buddhist who notes “anxiety arising” is not neutrally reporting a mental event; they are employing a phenomenological vocabulary shaped by Buddhist tradition.

This is not relativism—it is not saying that any description is as good as any other. It is saying that the practice of self-description is always embedded in a form of life, and the “self” that emerges is partly constituted by that form of life.

The Self Is Not a Private Theater

The image of the self as an inner theater—where mental events occur and are witnessed by an inner observer—is called into question by both thinkers.

Wittgenstein: The private theater presupposes a private language, which is incoherent. There is no inner stage where “beliefs” and “desires” perform for an audience of one. Psychological language is learned in public contexts and gets its meaning from public criteria.

Heidegger: The private theater presupposes the subject-object split—a mind “in here” observing contents. But Dasein is not first a mind and then in a world; it is always already Being-in-the-world. The inner/outer distinction is derivative of a more primordial involvement.

Authenticity Is Not Accuracy

The goal of self-knowledge, on both accounts, cannot be simply accuracy—getting the correct description of inner facts. There may be no such facts, or if there are, no way to describe them that does not already shape them.

Wittgenstein’s alternative: Clarity about how our language works, freedom from the confusions that beset us when language goes on holiday. The goal is not knowing more about yourself but being less confused about what you’re doing when you talk about yourself.

Heidegger’s alternative: Authenticity—taking over your existence rather than drifting with das Man. The goal is not accurate self-description but owning your thrownness and projection, existing as yourself rather than as “one.”

Both alternatives are practical rather than theoretical. They are not about getting better information but about living differently.

The Role of Silence

Both thinkers give silence an unusual importance.

Wittgenstein: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” The deepest things—the meaning of life, ethics, the self as limit of the world—cannot be said. They can only be shown. This echoes mystical traditions East and West.

Heidegger: The poet listens for what language wants to say. Authentic existence requires “reticence” (Verschwiegenheit)—not the chatter of das Man but a holding back that lets Being speak. This echoes Eckhart: the soul must be empty for the Word to be born.

Self-knowledge, in both cases, may ultimately require not more speech but less—not more introspection but more attending, not more theory but more practice.

Part V: A Revised Taxonomy

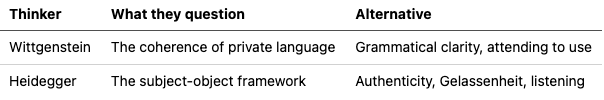

Adding Wittgenstein and Heidegger to our eleven psychologies requires a new category: those who question the medium of self-knowledge itself.

The Full Taxonomy

Those who assume a self and seek to know it:

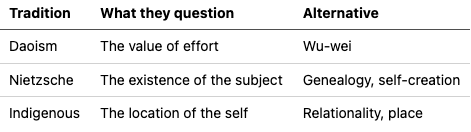

Those who question the self:

Those who question the medium:

The Question Behind the Questions

Wittgenstein and Heidegger do not simply add two more options; they question whether the question “how do I know myself?” makes sense in the way we usually assume.

Wittgenstein: The question presupposes that “self” names an object and “know” names a relation of accessing private contents. But this grammar may be confused. Dissolve the confusion, and the question may dissolve too—not because we find the answer but because we stop being gripped by the question.

Heidegger: The question presupposes a subject who stands over against itself as object. But Dasein is not a subject. It is Being-in-the-world, existence, care. The question “how do I know myself?” may be malformed—a remnant of the Cartesian tradition that Heidegger seeks to overcome.

This is not nihilism about self-knowledge. Both thinkers have plenty to say about human existence. But they suggest that the way we frame the question may be part of the problem.

Conclusion: The Limits of the Speakable

We have now traced thirteen perspectives on self-knowledge—and the last two question whether the project is coherent at all.

Wittgenstein shows that the language we use to describe inner states does not work the way we naively assume. There is no private theater, no beetle in the box. Psychological language is public, criterial, embedded in forms of life. Self-knowledge cannot be simple introspective access because there is nothing of the right sort to access.

Heidegger shows that the framework of subject and object, self and world, is not a neutral starting point but a historical construction that conceals more primordial ways of being. The self that asks “who am I?” is already constituted by language and tradition. Authentic existence requires not better introspection but a different way of being—owning one’s thrownness, listening for what language discloses.

Both point beyond themselves toward what cannot be said. Wittgenstein: silence. Heidegger: the mystery. Both suggest that the deepest “self-knowledge” may not be knowledge in the propositional sense at all.

This is not a counsel of despair. It is an invitation to hold our self-descriptions more lightly—to recognize them as tools in language-games rather than mirrors of inner facts. It is an invitation to attend to how we use words, rather than assuming we know what we mean. It is an invitation to exist authentically, rather than to analyze endlessly.

The history of self-relation now includes not only eleven psychologies but a meta-level reflection on the limits of what can be said about the self at all. Perhaps those limits are where the real work begins.

Selected Sources

Wittgenstein:

-

Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), trans. Ogden or Pears/McGuinness

-

Philosophical Investigations (1953), trans. Anscombe

-

The Blue and Brown Books (1958)

-

On Certainty (1969)

-

Hacker, P.M.S. Wittgenstein: Meaning and Mind

-

Cavell, Stanley. The Claim of Reason

Heidegger:

-

Being and Time (1927), trans. Macquarrie and Robinson, or Stambaugh

-

“Letter on Humanism” (1947), in Basic Writings, ed. Krell

-

“The Question Concerning Technology” (1954), in Basic Writings

-

Discourse on Thinking (1959), trans. Anderson and Freund (contains “Memorial Address” on Gelassenheit)

-

Elucidations of Hölderlin’s Poetry (various), trans. Hoeller

-

Dreyfus, Hubert. Being-in-the-World: A Commentary on Heidegger’s Being and Time

-

Polt, Richard. Heidegger: An Introduction

Secondary on Both:

-

Rorty, Richard. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature

-

Taylor, Charles. Philosophical Arguments (esp. “Heidegger, Language, and Ecology”)

-

Mulhall, Stephen. Inheritance and Originality: Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Kierkegaard