Why Power Chose Materialism—and What Was Lost

Published 2025-12-18

There is a question that hovers at the edge of respectable discourse, asked in whispers by those who sense something has been taken from them but cannot name it: Was the disenchantment of the world an accident, or was it useful to someone?

The honest answer is uncomfortable. The shift toward materialism—the systematic replacement of soul with psychology, conscience with conditioning, meaning with mechanism—was not a conspiracy. But it was not an accident either. It was a selection. Ideas that flattened human beings into measurable, predictable, governable units spread because they worked—not for the humans being flattened, but for the systems doing the measuring.

This is not paranoia. It is political anthropology. And understanding it is the first step toward recovering what was lost.

Related:

I. The Trajectory: From Soul to Subject

The intellectual shift is real and traceable. Consider the arc from the seventeenth century to the nineteenth:

John Locke (1689): The mind begins as a blank slate. Ideas derive from sensation. The soul, if it exists, leaves no mark that cannot be explained by experience.

David Hume (1739): The self is a bundle of impressions. Causality is habit. What we call the soul is nothing but a convenient fiction for organizing perceptions.

Jeremy Bentham (1789): Value reduces to pleasure and pain. Morality is calculation. The human being is a utility-maximizing machine whose inputs and outputs can be measured, predicted, and optimized.

Auguste Comte (1830–1842): Humanity progresses through stages—theological, metaphysical, positive. The final stage dispenses with God and abstraction alike, replacing them with science as the sole basis for knowledge and society.

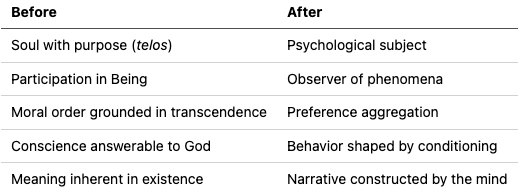

This is not merely epistemology. It is a redefinition of what a human being is:

The question is not whether this shift occurred—it did, and it is well-documented. The question is why these ideas spread, why they were adopted by institutions, why they became the operating system of modernity.

II. The Utility of Flatness

Here is where the uncomfortable truth emerges. Materialist anthropology systematically benefits power—not through conspiracy, but through selection pressure.

A. Legibility

The political scientist James C. Scott introduced the concept of legibility: the degree to which a population can be seen, measured, and administered by the state. Forests must be simplified into timber yields. Cities must be rationalized into grids. And human beings must be reduced to data points.

A spiritual human is:

-

Inward, oriented toward invisible goods

-

Answerable to God, conscience, or natural law

-

Capable of martyrdom, of valuing something more than survival

-

Illegible

A materialist human is:

-

Measurable in preferences, behaviors, outputs

-

Predictable through incentives and conditioning

-

Governable through policy levers

-

Optimizable

No conspiracy is required. States, corporations, and bureaucracies simply prefer models of humanity that work for administrative purposes. Ideas that render humans legible spread through institutions because institutions select for them.

B. The Dissolution of Rival Authorities

Spiritual frameworks introduce competing sovereignties. If a person answers to God, to natural law, to dharma, to conscience—then that person has a loyalty that precedes and potentially overrides the state.

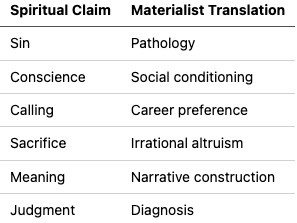

Materialism collapses these rivals:

This is not hidden. It is explicit in the founding documents of modern social science. Comte openly proposed replacing religion with positivism as a technology of social order. Bentham wrote treatises on how to manage populations through the manipulation of pleasure and pain. The project was stated plainly: render transcendence irrelevant.

III. The Architects Speak

The claim that materialism was selected for its utility is strengthened when we read what the architects themselves wrote.

Bentham: Religion as Instrument

Jeremy Bentham’s views on religion were so controversial that he published his most explicit critique under a pseudonym. In Analysis of the Influence of Natural Religion on the Temporal Happiness of Mankind (1822), attributed to “Philip Beauchamp,” Bentham catalogued what he saw as religion’s harms: it taxes emotional well-being with fear, scruples, and guilt; it prejudices the intellect; it splinters society into factions.

But Bentham’s concern was not merely philosophical—it was administrative. Religion, for him, was useful only insofar as it promoted obedience. His Panopticon—the prison design where inmates could be watched at all times without knowing when they were being observed—was not an afterthought. It was the architectural expression of his anthropology: human beings as subjects to be surveilled, measured, and corrected.

The Panopticon was designed not just for prisons but for “any sort of establishment, in which persons of any description are to be kept under inspection”—including factories, hospitals, schools, and workhouses. Bentham understood that the same logic applied everywhere: what cannot be measured cannot be administered.

Comte: The Religion of Management

Auguste Comte went further. He proposed not merely to critique religion but to replace it. His “Religion of Humanity” would have priests (secular sociologists), sacraments, a calendar of saints (great scientists and thinkers), and rituals—all organized around the veneration of Humanity rather than God.

Comte wrote explicitly:

“Thus Positivism becomes, in the true sense of the word, a Religion; the only religion which is real and complete; destined therefore to replace all imperfect and provisional systems resting on the primitive basis of theology.”

The religion would be administered by experts. A “spiritual priesthood of secular sociologists would guide society and control education and public morality.” The actual government would remain in the hands of businessmen and bankers, but the meaning-making apparatus—the soul-shaping institutions—would be managed by technocrats.

Thomas Huxley called Comte’s system “Catholicism minus Christianity.” The structure of spiritual authority would remain; only the content would change. The hierarchy, the rituals, the sense of sacred order—all preserved. The transcendent referent—removed.

This was not an attack on the form of religion. It was a capture of religion’s social function for administrative purposes.

The Explicit Program

These were not secret documents. They were published programs. The intent was not “destroy the spirit” but something subtler and more effective: render it irrelevant. Replace it with a functional substitute that serves the same social purposes without the inconvenient features—the rival loyalties, the potential for martyrdom, the claims that override the state.

IV. The Consequences Weber Named

Max Weber, writing a century after Bentham and Comte, looked at what their program had produced and gave it a name: die Entzauberung der Welt—the disenchantment of the world.

“The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the ‘disenchantment of the world.’ Precisely the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life either into the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations.”

Virtue had retreated from public life.

And, in its place, material goods reigned.

“Material goods have gained an increasing and finally inexorable power over the lives of men as at no previous period in history.”

The result was what Weber called the “iron cage”:

“In Baxter’s view the care for external goods should only lie on the shoulders of the saint like ‘a light cloak, which can be thrown aside at any moment.’ But fate decreed that the cloak should become an iron cage.”

Weber did not predict whether disenchantment would continue. He saw it as an open question whether new prophets might arise, whether old traditions might revive, or whether humanity would simply resign itself to “specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart”—a nullity that “imagines it has attained a level of civilization never before achieved.”

V. The Counter-Tradition: Those Who Refused

Not everyone accepted the terms of disenchantment. There is a counter-tradition of thinkers who saw what was happening and named it—who refused to mistake administrative convenience for philosophical truth.

Pascal: The Terror of Infinite Spaces

Two centuries before Weber, Blaise Pascal felt the coming void. The new cosmology—Copernicus, Galileo, the infinite universe—had displaced humanity from the center. And Pascal, unlike many of his contemporaries, did not pretend this was comfortable.

“When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in the eternity before and after, the little space which I fill, engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I am ignorant, and which know me not, I am frightened, and am astonished at being here rather than there; for there is no reason why here rather than there, why now rather than then.”

And then the famous line:

“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

Pascal saw that the new physics offered no meaning—only mechanism. The universe that emerged from the scientific revolution was vast, indifferent, and silent. And Pascal refused to pretend that this silence was an answer rather than a question.

But Pascal also refused despair. Against the void, he insisted on the dignity of thought:

“Man is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature; but he is a thinking reed. The entire universe need not arm itself to crush him. A vapour, a drop of water suffices to kill him. But, if the universe were to crush him, man would still be more noble than that which killed him, because he knows that he dies and the advantage which the universe has over him; the universe knows nothing of this.”

The universe is larger. But it does not know. And in that difference—in consciousness, in the capacity for meaning—Pascal found something that mere extension could not contain.

Simone Weil: Gravity and Grace

In the twentieth century, Simone Weil offered a vocabulary for what materialism could not name. She distinguished between gravity—the automatic, downward pull of necessity, selfishness, and mechanical causation—and grace—the irruption of something from beyond the closed system, something that lifts rather than presses.

“All the natural movements of the soul are controlled by laws analogous to those of physical gravity. Grace is the only exception.”

Weil saw that materialism was not wrong about gravity. The world is governed by necessity. Cause and effect do operate mechanically. Human psychology is subject to predictable forces. The error was in mistaking gravity for the whole of reality—in assuming that because the downward pull is real, there is nothing that pulls upward.

Her concept of decreation pointed toward what materialism cannot imagine: the voluntary undoing of the self’s automatic expansion, the opening of a space through which grace might enter.

“Decreation: to make something created pass into the uncreated. Destruction: to make something created pass into nothingness. A blameworthy substitute for decreation.”

The materialist can only imagine destruction—the reduction of meaning to mechanism, of soul to psychology, of transcendence to illusion. Weil named another possibility: the transformation of the created into something that participates in what is beyond creation.

This is not an argument. It is an invitation to attend—to notice whether the language of gravity exhausts your experience of being alive.

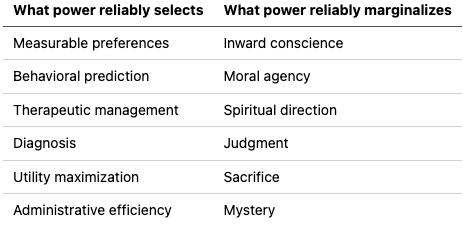

VI. The Pattern of Selection

Across centuries, the pattern repeats. Ideas that serve power—that make humans legible, predictable, governable—spread through institutions. Ideas that preserve mystery, that ground rival authorities, that make martyrdom conceivable—these are marginalized, defunded, ridiculed, or simply ignored.

This is not conspiracy. It is selection pressure operating through:

-

Patronage: Which ideas get funded, published, promoted?

-

Institutional adoption: Which frameworks do universities, corporations, and states find useful?

-

Cultural amplification: Which assumptions become so pervasive they feel like common sense?

The ideas that won were not necessarily truer. They were more useful to the systems that adopted them.

VII. What Was Lost

The consequences are visible in the texture of contemporary life:

-

Loss of meaning: Weber’s “specialists without spirit, sensualists without heart”

-

Identity fragility: If the self is merely constructed, it can be deconstructed

-

Alienation: No connection to anything larger than individual preference

-

Hyper-conformity: Without transcendent ground, social pressure becomes absolute

-

Obsession with recognition: When vertical transcendence closes, horizontal validation becomes everything

When people sense that “something has been taken from them,” this is what they are sensing. Not a specific doctrine, but an anthropology—a picture of what a human being is that leaves out everything that cannot be measured.

The modern subject is ontologically thinner than its predecessors. It has more information and less wisdom, more options and less direction, more freedom and less capacity to use it.

VIII. The Possibility of Recovery

The point is not nostalgia. The point is to recognize that what exists is not what had to exist.

The materialist anthropology was selected, not discovered. It won because it was useful, not because it was true. And the question of truth remains open.

Consider: Does your experience of being alive reduce entirely to pleasure and pain? Is conscience nothing but social conditioning? Is meaning nothing but narrative construction? Is the love you have felt for another person merely a strategy for genetic replication?

If you hesitate—if something in you resists these reductions—then you have encountered what the selection process was designed to eliminate: the intuition that you are more than what can be measured.

This intuition is not an argument. But it is a starting point. The counter-tradition—Pascal, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Weil—offers resources for those who wish to explore it. They are not popular in the academy, not because they were refuted but because they are inconvenient. They name what power prefers to leave unnamed.

Simone Weil wrote:

“Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.”

Attention means staying with what resists easy categorization. It means refusing the premature closure that administrative convenience demands. It means allowing the question of transcendence to remain open, even when—especially when—there is pressure to declare it settled.

The eternal silence of infinite spaces frightened Pascal. But he noticed that he was frightened—and that this noticing, this awareness of awareness, was itself something the infinite spaces could not contain.

Perhaps the recovery begins there: in the attention that notices what materialism cannot name.

Coda: Not a Plot, But a Drift

The strongest formulation is not conspiracy but selection:

Materialism was not invented to destroy the spirit, but it was selected, promoted, and institutionalized because it dissolves spiritual authority in favor of administrative control.

This is the history we inherit. The question is what we do with it.

We can accept the terms of disenchantment—assume that the questions are settled, that the reductions are final, that the iron cage is inescapable.

Or we can recognize that the cage was built, that the builders had interests, and that the materials they excluded are still available.

The spirit was not destroyed. It was declared irrelevant. And declarations, unlike laws of physics, can be withdrawn.

What remains is attention—the willingness to notice what the dominant framework cannot account for, to stay with the questions it was designed to close, to allow the possibility that the silence of infinite spaces is not the last word.

Grace, Weil said, is the only exception to gravity.

The exception remains possible.