The Two Filters: Why Reasonable Ideas Die

Published 2025-12-18

We are taught that good ideas win. That truth, once articulated, spreads naturally—that reason prevails, that justice rises, that the arc of history bends. This is a comforting myth. It is also, as a matter of historical record, false.

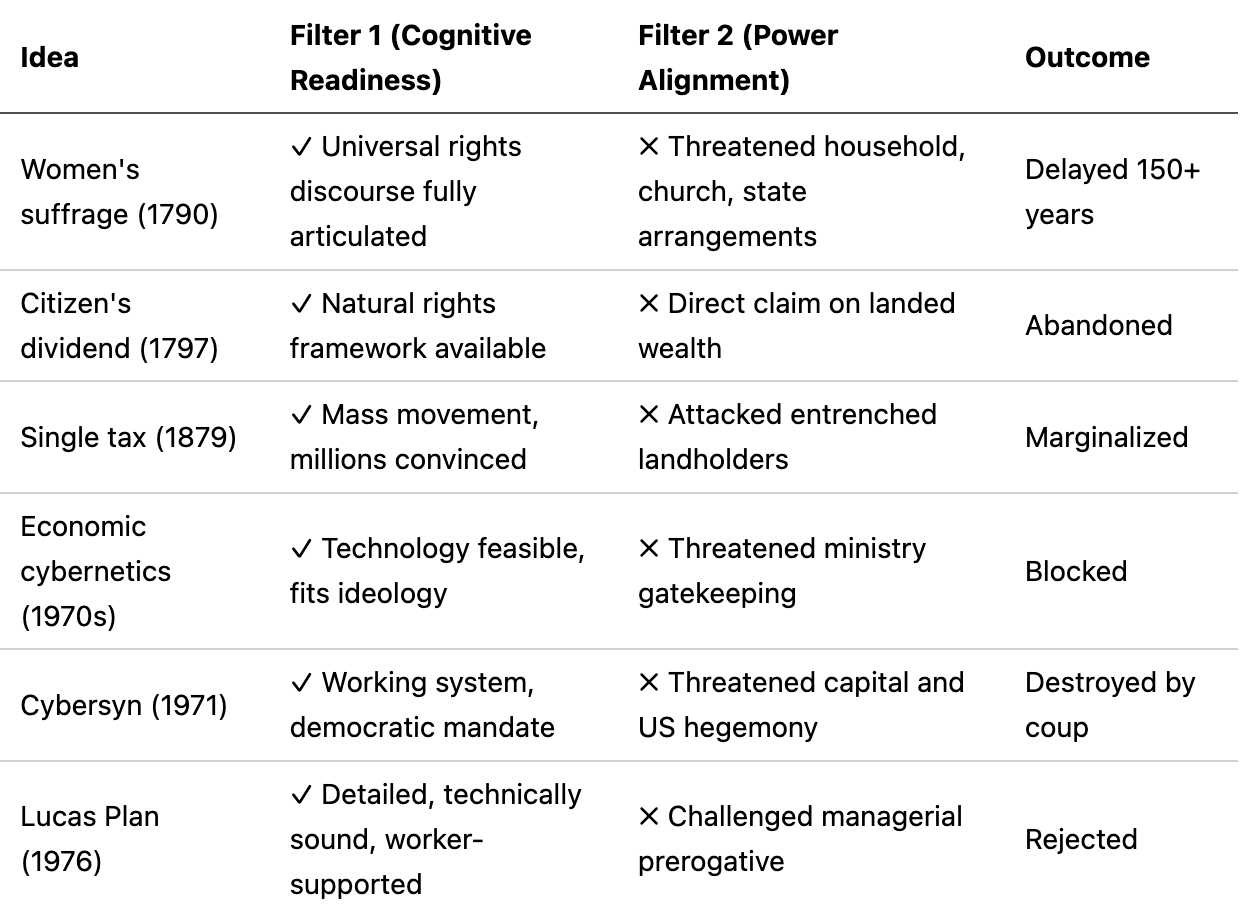

Ideas do not succeed because they are true. They succeed because they pass through two filters:

Filter 1: Cognitive Readiness — Can society hear this idea? Is the conceptual groundwork laid? Are the institutions, vocabularies, and audiences prepared to receive it?

Filter 2: Power Alignment — Can elites use this idea, or at least survive it? Does it threaten property, sovereignty, or the gatekeeping functions that powerful actors depend upon?

Darwin and Freud passed both filters. They arrived when culture was primed to need them, and when their frameworks could be adopted by universities, medical establishments, and secular elites without upending existing hierarchies. Darwin offered order without God—a mechanism for the design that Victorian society already doubted. Freud offered guilt without sin, confession without priest—translating Christian moral grammar into therapeutic language that secular modernity could accept. Both felt revolutionary while preserving the essential structure of power.

But what of the ideas that passed Filter 1 and failed Filter 2? What of the thinkers who articulated concepts society could clearly hear—concepts that gained traction, drew followers, generated movements—yet were blocked, defanged, or erased because they threatened those who controlled resources and institutions?

This is the history we are not taught. And understanding it is essential to freeing our minds from the habits of thought that make us mistake what happened for what was possible.

I. The Ghosts of 1790: When Universal Rights Were Too Universal

The French Revolution cracked open the grammar of rights. “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” echoed through the streets of Paris. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaimed that men are born free and equal in rights. The conceptual infrastructure for universal claims was fully operational.

It was in this moment that the Marquis de Condorcet published his essay On the Admission of Women to the Rights of Citizenship (1790). His argument was devastatingly simple: if rights derive from reason and moral capacity, and if women possess these capacities, then excluding them is incoherent. He opened with an indictment of his most enlightened colleagues:

“Habit can so familiarize men with violations of their natural rights that those who have lost them neither think of protesting nor believe they are unjustly treated. Some of these violations even escaped the notice of the philosophers and legislators who enthusiastically established the rights common to all members of the human race, and made these the sole basis of political institutions.”

Condorcet named the problem: habit had made injustice invisible even to those who proclaimed themselves champions of justice. And then he asked the question that should have ended the debate:

“Is there a stronger proof of the power of habit even among enlightened men than seeing the principle of equality of rights invoked in favor of three or four hundred men deprived of their rights by an absurd prejudice, and at the same time forgetting those rights when it comes to twelve million women?”

The logic was impeccable. The revolution’s own principles demanded it. Filter 1 was passed: society could hear the argument. The vocabulary existed, the audience was assembled, the moment was ripe.

What if only Filter 1 mattered? Women’s suffrage in France in the 1790s. Full political participation. The restructuring of household, church, and state a century and a half earlier than it occurred.

But Filter 2 intervened. Extending political agency to women threatened existing arrangements of household authority, ecclesiastical power, and governing coalitions. The idea was not refuted—it was abandoned. Condorcet himself was declared an outlaw by the Jacobins and died in prison. The campaign for women’s rights proved, as one historian put it, “the most difficult prejudice to uproot.”

The revolution that proclaimed universal rights granted them only to those whose rights did not threaten the powerful.

II. Thomas Paine and the Ground-Rent That Never Was

In 1797, Thomas Paine—fresh from revolutions on two continents—published Agrarian Justice. His argument cut to the foundation of property itself. The earth, he wrote, is common inheritance. What individuals create, they may own. But land itself?

“Men did not make the earth. It is the value of the improvements only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property. Every proprietor owes to the community a ground rent for the land which he holds.”

Paine proposed a practical mechanism: a fund created from ground-rents on cultivated land, used to pay every person a lump sum at adulthood and a pension in old age. Not charity—inheritance. The natural birthright of every human being to the earth that preceded them.

“Every proprietor, therefore, of cultivated lands, owes to the community a ground-rent... to every person, rich or poor... because it is in lieu of the natural inheritance, which, as a right, belongs to every man.”

The conceptual framework was in place. Revolutionary-era natural rights discourse made arguments about common inheritance intelligible. The language was accessible, the moment opportune. Filter 1: passed.

What if only Filter 1 mattered? A citizen’s dividend in 1800. Universal basic income at the birth of industrial capitalism. A structural check on the accumulation that would define the next two centuries.

But Paine’s proposal implied permanent claims on landed wealth—a hard collision with the interests of property elites on both sides of the Atlantic. The idea found admirers but no institutional sponsors. It was not so much refuted as filed away, to be rediscovered periodically by reformers who faced the same structural opposition.

The man who helped birth two republics died in obscurity. Only six mourners attended his funeral.

III. Henry George and the Single Tax That Almost Won

By the 1870s, the Gilded Age had made land monopoly visible to anyone who cared to look. Fortunes accumulated not from labor but from ownership—from being positioned to capture the rising value of land as communities grew around it. Into this moment stepped Henry George, a San Francisco journalist who had seen the paradox firsthand:

“This association of poverty with progress is the great enigma of our times. It is the riddle which the Sphinx of Fate puts to our civilization, and which not to answer is to be destroyed.”

His book Progress and Poverty (1879) became one of the best-selling works of the nineteenth century. By John Dewey’s estimate, it “had a wider distribution than almost all other books on political economy put together.” Helen Keller found in it “a splendid faith in the essential nobility of human nature.” Tolstoy was preaching its ideas on his deathbed. Churchill, Russell, and Einstein all acknowledged its force.

George’s diagnosis was precise:

“The great cause of inequality in the distribution of wealth is inequality in the ownership of land... The ownership of land is the great fundamental fact which ultimately determines the social, the political, and consequently the intellectual and moral condition of a people.”

His remedy: a single tax on land values, capturing for the community the value that community growth creates, while freeing labor and enterprise from taxation entirely.

George ran for Mayor of New York in 1886 and nearly won—finishing ahead of Theodore Roosevelt, losing only to Tammany Hall’s machine candidate under circumstances widely considered fraudulent. The movement he sparked swept across the English-speaking world. In Britain, a 1906 survey of parliamentarians found George more popular than Shakespeare.

Filter 1: passed spectacularly. Society heard the argument. Millions were convinced. The conceptual infrastructure for land reform was fully constructed.

What if only Filter 1 mattered? The single tax implemented. Land speculation ended. The dynamic by which community-created value flows to private landowners—the mechanism behind housing crises and land inequality to this day—structurally interrupted.

But George’s tax directly attacked entrenched landholders and the institutions allied with them. Organized opposition framed it as an assault on property itself. Political support fragmented. The idea that had mobilized millions was channeled into policy margins and academic footnotes.

IV. The Workers’ Plans That Were Refused

The twentieth century produced two remarkable episodes in which workers themselves designed alternatives to the systems that employed them—and were refused not because their plans were unworkable, but because they challenged who controlled production.

Chile’s Cybersyn (1971–1973)

When Salvador Allende became the world’s first democratically elected socialist president, he faced an immediate problem: how to coordinate a nationalized economy without reproducing Soviet-style centralization. The British cybernetician Stafford Beer was brought in to design a solution.

Project Cybersyn proposed running the national economy in real time—connecting factories via telex to a central operations room where economic data flowed continuously, enabling rapid response to problems while preserving worker autonomy at the local level. It was, in essence, an early internet designed for democratic economic management.

The system was tested during the October 1972 strike, when opposition truckers attempted to bring down the economy. Using Cybersyn’s primitive network, the government tracked unused vehicles and unblocked routes, maintaining essential services. A senior minister later stated that the government would have collapsed without it.

When asked about worker control, Allende’s response was unambiguous: “El maximo.”

Filter 1: passed. The technology was feasible. The conceptual framework—cybernetics applied to economic democracy—was fully developed. The system was working.

What if only Filter 1 mattered? Chile as a laboratory for networked economic democracy. An alternative to both market capitalism and Soviet planning, developed by a democratic government with popular support.

But on September 11, 1973, Pinochet’s coup destroyed not just Allende but every trace of Cybersyn. The operations room was demolished. The dream of economic democracy was replaced by the nightmare of Milton Friedman’s “shock therapy.” Filter 2 was applied with bullets.

The Lucas Plan (1976)

In Britain, workers at Lucas Aerospace faced mass layoffs. Rather than accept redundancy, the Shop Stewards’ Combine Committee did something unprecedented: they asked workers across all skill levels what socially useful products they could make instead.

The response was extraordinary. Over 150 designs emerged—wind turbines, hybrid car engines, heat pumps for social housing, kidney machines, life-support systems for ambulances. Many anticipated technologies that would only become mainstream decades later.

Mike Cooley, a key organizer, captured the underlying challenge:

“It is an insult to our skill and intelligence that we could produce a Concorde but not enough paraffin heaters for all those old-age pensioners who die in the cold.”

The Plan argued for redirecting government defense spending toward production “useful to the community at large.” Tony Benn called it “one of the most remarkable exercises that has ever occurred in British industrial history.”

Filter 1: passed. The Plan was technically detailed, economically argued, and demonstrated massive worker engagement. The Financial Times called it “one of the most radical alternative plans ever drawn up by workers for their company.”

What if only Filter 1 mattered? Worker-designed conversion from weapons to social production. A precedent for democratic control over technology and manufacturing priorities. A living answer to the false choice between jobs and social need.

But Lucas management rejected the Plan outright. They resented “their workers telling them what to do” and insisted on the company’s commitment to defense production. The union leadership offered only half-hearted support—the Plan’s radical implications made them nervous. Cooley was eventually fired and the Combine weakened.

As one shop steward reflected: “Quite honestly, I thought the Company would have welcomed it... that they would see it as constructive trade unionism.” He had passed Filter 1. He had failed to account for Filter 2.

V. The Soviet Internet That Bureaucracy Killed

Even within the Soviet system—where one might expect central planning to embrace technological rationalization—Filter 2 operated with brutal efficiency.

In the 1960s, the cybernetician Viktor Glushkov proposed OGAS: a nationwide computer network connecting thousands of mainframe computers to enable real-time economic planning. The system anticipated cloud computing, electronic transactions, and networked data management decades before the Western internet.

Glushkov believed his task was “not only scientific and technical, but also political.” He understood that better information flows would transform power relationships.

The proposal faced opposition from an unexpected direction: the very ministries that would supposedly benefit. Each ministry had built its own computer centers, controlled its own data, accumulated its own power. By 1971, the number of internal ministry systems had grown sevenfold—but they used incompatible hardware and software, forming no cross-agency network.

The historian Slava Gerovitch called the result “InterNyet”:

“Ministry officials realized that there were many ways to skin the cybernetic cat without necessarily losing their grip on power... Now the ministries did not have to share information/power with any rival agency.”

Filter 1: passed. The technology was feasible. The ideological fit with socialist planning was obvious. The proposal was approved by the Politburo—then immediately scaled back when leaders realized its political implications.

What if only Filter 1 mattered? A Soviet internet in the 1970s. Real-time economic coordination. Possibly a different trajectory for both the USSR and global technology development.

But the ministries won. The system that promised to rationalize planning was blocked by the bureaucracy whose inefficiencies it would have exposed. Glushkov died in 1982, his vision unrealized. Within a decade, the Soviet system would collapse—in part from the very planning failures his network was designed to address.

VI. The Pattern

Across two centuries, the pattern repeats:

What power reliably vetoes, even when society is ready:

-

Direct threats to property: Paine’s ground-rent, George’s land tax

-

Rival sovereignty: Workers’ councils, guild socialism, Cybersyn

-

Gatekeeping disruption: OGAS threatening Soviet ministries

-

Control of technology: Lucas Plan, Cybersyn

-

Expanded agency for subordinated groups: Condorcet on women

VII. Freeing the Mind

Why does this matter now?

Because we walk through a museum of invisible alternatives. Every “natural” arrangement we inhabit—the distribution of property, the structure of work, the limits of citizenship—was once contested. Ideas that seem utopian today had mass followings, detailed plans, working prototypes. They failed not because they were impossible but because they were blocked.

Understanding the two filters accomplishes something crucial: it separates the question “Was this idea any good?” from the question “Did this idea succeed?” These are different questions with different answers.

It also illuminates why certain ideas spread “overnight” while others languish for generations. Darwin and Freud didn’t succeed because they were more correct than Paine or Condorcet or George. They succeeded because their ideas could be adopted by powerful institutions without threatening the core structure of property and authority. They offered transformation without upheaval—metaphysical revolution coupled with social continuity.

To put it another way: Darwin and Freud did not uncover the divine spark—they explained why it could be ignored without panic.

The ideas that died did the opposite. They promised transformation with upheaval. They threatened what Foucault would call “technologies of power”—not just this or that arrangement, but the gatekeeping functions through which elites maintain control. They offered not just new answers but new questions: Who owns the earth? Who controls production? Who decides what counts as useful?

These questions remain open. The filters still operate. But knowing they exist is the first step toward passing through them—or, perhaps, dismantling them altogether.

Coda: The Question for Our Time

We face problems today that require ideas of similar scope: climate transformation, artificial intelligence governance, the ownership of data, the future of work. Some of these ideas will be cognitively ready—articulable, comprehensible, buildable. Fewer will align with existing power structures.

The history traced here suggests that the ideas most likely to spread quickly are not necessarily the best ideas—they are the ideas that preserve essential power arrangements while changing surface conditions. The deeper transformations will face the obstacles that Condorcet, Paine, George, Glushkov, Beer, and Cooley faced: not refutation but rejection, not argument but abandonment, not defeat but erasure.

If we want different outcomes, we need to understand the game we’re playing. Filter 1 is necessary but not sufficient. Ideas that pass only Filter 1 become ghosts—honored in retrospect, mourned in footnotes, celebrated as “ahead of their time” while the structures they challenged remain intact.

To free our minds from current habits of thought is to recognize that what exists is not what had to exist. The museum has other wings we never visit. The paths not taken were paths, not phantoms.

And the question the Sphinx puts to every civilization remains: not whether you can conceive justice, but whether you will permit it.