Countering Materialism

Published 2025-12-19

Related:

There is a counter-tradition in Western thought—a line of thinkers who resisted the materialist reduction before it became the water we swim in. Pascal, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Simone Weil.

You probably know these names. You may have dismissed them as religious apologists, pre-scientific mystics, or at best interesting literary figures whose philosophical contributions have been superseded by neuroscience and evolutionary psychology.

This essay will argue that you’ve made an error. Not the error of rejecting their theological conclusions—you may be right to do so. The error is in assuming they didn’t understand what you understand. They did. They understood it better.

These thinkers were not naive believers defending inherited dogma against the onslaught of reason. They were diagnosticians. They had taken the materialist position seriously—in some cases, lived it to its logical conclusions—and found it not wrong but incomplete in a way that produces specific, predictable pathologies.

What they saw, we now have data for. What they predicted, we now measure. The question is whether you’re willing to notice.

I. The Trap of Assumed Superiority

Before engaging with these thinkers, we need to address a prejudice that will otherwise prevent you from hearing them.

The modern educated person approaches pre-20th century religious thinkers with a specific assumption: they believed what they believed because they didn’t know what we know. If Pascal had understood neuroscience, he wouldn’t have needed God. If Kierkegaard had read Darwin, he would have seen through his own anxiety. If Dostoevsky had access to SSRIs, the Underground Man would have been fine.

This assumption is flattering to us. It positions our era as the culmination of intellectual progress—we who have finally seen through the illusions that comforted our ancestors. It also makes these thinkers safe: we can appreciate them aesthetically without being challenged by them.

But what if the assumption is wrong?

What if these thinkers understood the materialist position—understood it from the inside, in some cases before it had fully articulated itself—and found it not primitive but inadequate to the phenomena? What if they were not defending inherited belief against reason, but using reason to expose the limitations of a specific kind of reasoning?

The test is simple: read them carefully and see whether their diagnoses match the symptoms you observe in yourself and in your civilization. If they were merely pre-scientific, their predictions should miss. If they saw something real, the predictions should land.

II. Pascal: The Mathematician Who Felt the Void

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) was not a theologian defending tradition. He was one of the greatest mathematicians of his era—inventor of the first mechanical calculator, contributor to probability theory, pioneer in fluid mechanics. He understood the scientific revolution from the inside because he was helping to create it.

And he was terrified.

“The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

This is not the fear of a man who doesn’t understand the new cosmology. It is the fear of a man who understands it perfectly. Pascal felt what it meant for humanity to be displaced from the center of a meaningful cosmos to a speck in infinite void. He didn’t reject the new science—he accepted it, and then asked: now what?

What Pascal saw—and what makes him so uncomfortable for modern readers—is that the scientific revolution solved certain problems while creating others that it had no tools to address. It could tell you what the universe was made of. It could not tell you what you were for.

His diagnosis centers on what he called divertissement—usually translated as “diversion” or “distraction.” Pascal observed that humans cannot sit quietly in a room alone. We compulsively seek activity, entertainment, business—anything to avoid confronting our condition:

“I have discovered that all the unhappiness of men arises from one single fact, that they cannot stay quietly in their own chamber.”

This sounds like a moral failing. Pascal insists it’s something deeper: a structural feature of human existence. We flee from stillness because stillness forces us to confront what we are—finite, mortal, and (without some transcendent framework) meaningless.

The king, who has everything, still needs entertainers. The wealthy man who could rest still chases new projects. The successful person who has “made it” still can’t stop. Why? Not because they’re greedy or restless by nature. Because stopping would mean facing the void.

“Being unable to cure death, wretchedness, and ignorance, men have decided, in order to be happy, not to think about such things.”

Pascal is not arguing that we should think about death constantly. He’s making an empirical observation: we have structured our entire civilization around not thinking about it. Our busyness is not incidental—it’s defensive. Our entertainment is not leisure—it’s medication.

The test: Does this description match what you observe? Do you find it difficult to be alone with your thoughts without reaching for a phone, a task, a distraction? Do you know anyone who has achieved material success and found peace? Or do they just find new things to chase?

If divertissement is real, it has implications. It means that the restlessness you feel is not a personal failing to be solved by better productivity systems. It’s a symptom of something your framework cannot address.

III. Kierkegaard: The Existing Individual Against the System

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) is sometimes called the father of existentialism, but this label obscures what he was actually doing. He was attacking systems—specifically, any system of thought that claimed to explain everything while leaving out the person doing the explaining.

His target was Hegel, whose philosophy claimed to comprehend the whole of reality in a rational system. But his critique applies equally to any totalizing framework—including the materialist one.

The core insight: a system can explain everything except the existence of the person using it.

Hegelian philosophy could tell you how history unfolds according to rational laws. It could not tell you what you should do tomorrow morning. Evolutionary psychology can tell you why humans in general seek status. It cannot tell you whether you should seek status or renounce it. Neuroscience can tell you which brain regions activate when you make a decision. It cannot make the decision for you.

Kierkegaard called this the gap between objective and subjective truth:

“An objective uncertainty, held fast through appropriation with the most passionate inwardness, is the truth, the highest truth attainable for an existing individual.”

This is not anti-intellectualism. Kierkegaard is not saying objective facts don’t matter. He’s saying that for an existing individual—someone who has to actually live, choose, and die—objective facts are not enough. You can know everything about the world and still not know how to live.

The materialist framework is objective through and through. It can tell you what humans are made of, how they evolved, why they behave as they do. What it cannot do is address you as an existing individual who must make decisions without complete information, who experiences anxiety about the future, who will die.

Kierkegaard diagnosed what he called despair—a sickness that comes from failing to become oneself. In The Sickness Unto Death, he identified forms of despair that most sufferers don’t even recognize:

“The greatest danger, that of losing one’s own self, may pass off as quietly as if it were nothing.”

You can lose yourself by becoming entirely absorbed in objective knowledge, in systems, in the general—while never confronting what it means to be this particular person facing these particular choices. The system explains everything; the existing individual who uses it remains unexplained and unaddressed.

The test: Do you sometimes feel that you understand the world quite well but still don’t know how to live in it? Do you find that more information doesn’t resolve your deepest uncertainties? Have you ever suspected that you’re living by default—following scripts you’ve absorbed rather than choices you’ve made?

If so, Kierkegaard suggests this isn’t a bug in your psychology to be fixed with more data. It’s the inevitable result of trying to live an existence that transcends any system, using only the tools the system provides.

IV. Dostoevsky: The Underground Man’s Prophecy

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) wrote Notes from Underground in 1864 as a response to a novel called What Is to Be Done? by Nikolai Chernyshevsky. That novel proposed that once humans understood their true interests through reason and science, they would naturally create a harmonious society—symbolized by the “Crystal Palace,” an actual building in London that represented technological progress and rational organization.

Dostoevsky’s Underground Man is a figure of contempt, a bitter, isolated, self-sabotaging narrator who nonetheless sees something the utopians cannot see: humans will destroy the Crystal Palace out of sheer spite, just to prove they’re not piano keys.

“What sort of free choice will there be when it comes down to tables and arithmetic, when all that’s left is two times two makes four? Two times two will make four even without my will. Is that what you call free choice?”

The Underground Man’s argument is not that reason is wrong. Two times two does equal four. His argument is that a human being is not the kind of thing that can live by arithmetic alone. Something in us rebels against being fully determined, fully explained, fully optimized.

“Two times two makes four is no longer life, gentlemen, but the beginning of death.”

If you could calculate the optimal path and always take it, you would no longer be a free being—you would be “a stop in an organ pipe.” So humans will do irrational things—harmful things, self-destructive things—simply to assert that they are not mechanical. This is not a failure of rationality. It is rationality defending something that rationality cannot capture.

Dostoevsky saw that the rational utopia, far from solving human problems, would produce a new kind of misery—the misery of beings who are conscious that they should be happy but can’t be. The Crystal Palace would be hell because it would leave nothing to struggle against, nothing to transcend, nothing to be.

The test: Have you ever done something self-destructive for no reason you can articulate? Have you ever sabotaged your own success? Do you sometimes feel trapped precisely when everything is going well?

If the Underground Man is right, these are not pathologies to be treated. They are symptoms of a being that cannot be reduced to its interests, rebelling against a framework that insists it can.

V. Simone Weil: Gravity and the Counter-Force

Simone Weil (1909-1943) is the most difficult of these thinkers to categorize. A French philosopher who worked in factories, fought in the Spanish Civil War, and died at 34 from tuberculosis exacerbated by self-imposed starvation in solidarity with occupied France—she lived her philosophy with a literalness that makes most intellectuals uncomfortable.

Her central metaphor is the opposition between gravity and grace.

Gravity, in Weil’s usage, is not just physical force. It is the name for everything in human psychology that pulls downward—toward self-expansion, self-protection, power, comfort. It is the default direction of the soul when nothing else acts on it.

“All the natural movements of the soul are controlled by laws analogous to those of physical gravity. Grace is the only exception.”

This is an extraordinary claim. Weil is saying that left to itself—without some counter-force—the soul will inevitably move toward heaviness, toward filling itself up, toward what she calls pesanteur (weight). The patterns we observe in human behavior—status-seeking, accumulation, domination—are not aberrations. They are the soul obeying gravity.

What materialism does, on this account, is remove everything that pulls upward. It eliminates the transcendent. It tells you that gravity is all there is, and that the feeling of being pulled toward something higher is an illusion produced by evolutionary pressures.

But the soul still exists. The longing still exists. With nothing to pull it upward, it collapses into itself.

Weil’s other key concept is attention—the capacity to look at what is without imposing your own needs onto it. True attention requires a kind of emptiness, a willingness to be receptive rather than grasping:

“The capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing: it is almost a miracle.”

The opposite of attention is what she calls “imagination which fills the void”—the compulsive mental activity that fills every empty space with fantasy, projection, compensation. We cannot tolerate the void, so we fill it with noise.

This connects directly to Pascal’s divertissement. The busyness, the distraction, the endless scroll—these are not neutral choices. They are the soul fleeing from a void it cannot face, filling the emptiness with anything rather than experiencing it directly.

The test: Can you sit in silence without reaching for stimulus? Can you look at another person’s suffering without immediately trying to fix it, explain it, or turn away? Can you tolerate not-knowing?

If not, Weil would say this is not a failure of willpower. It is gravity doing what gravity does. The question is whether you believe there is any counter-force, or whether gravity is simply all there is.

VI. What They Saw in Common

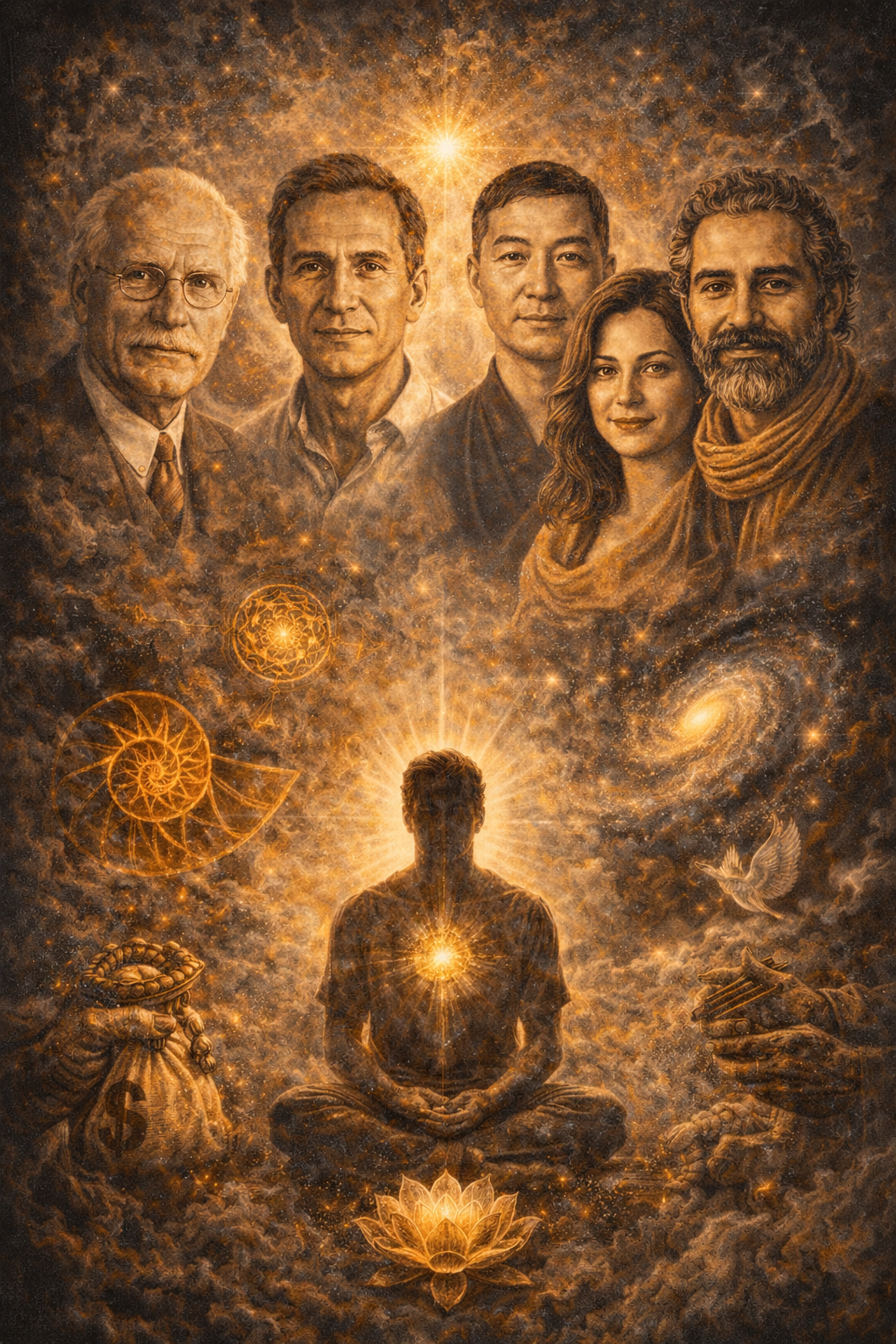

Despite their differences—Pascal the mathematician, Kierkegaard the ironist, Dostoevsky the novelist, Weil the mystic activist—these thinkers converge on several observations:

1. Humans require meaning that cannot be derived from facts.

All four saw that the human being is structured for transcendence—that we cannot function without a sense of purpose, significance, value that goes beyond mere survival. Materialism can explain why we feel this need (evolutionary psychology), but it cannot meet it. The explanation is not a substitute for the thing explained.

2. The attempt to live without transcendence produces specific pathologies.

Pascal’s divertissement (compulsive distraction), Kierkegaard’s despair (failure to become oneself), Dostoevsky’s spite (rebellion against optimization), Weil’s gravity (collapse into self-expansion)—these are different names for the same phenomenon: what happens to a being built for transcendence when transcendence is denied.

3. These pathologies are invisible from within the materialist framework.

If you assume that humans are just complex biological machines optimizing for survival and reproduction, then the symptoms look like random noise—personal failings, chemical imbalances, poor choices. The framework cannot see that the symptoms might be systematic responses to something the framework is missing.

4. The framework that produces the pathologies cannot diagnose them.

This is the trap. If you’re inside the materialist worldview, you have no tools for recognizing what’s missing. The dissatisfaction you feel gets attributed to not having enough—more money, more status, more experiences, more optimization. The solution is always more of the same, which makes the problem worse.

VII. A Note on What This Is Not

I am not arguing that these thinkers were right about everything. Pascal’s Wager has logical problems. Kierkegaard’s leap of faith may be epistemically unjustified. Dostoevsky’s Christianity came with unsavory politics. Weil’s asceticism killed her.

I am also not arguing that you should become religious. The counter-tradition is not primarily offering beliefs to adopt. It is offering diagnoses of a condition—a way of seeing what materialism systematically obscures.

The question is not whether their metaphysics is correct. The question is whether their phenomenology is accurate. Do their descriptions match what you experience? Do their predictions match what you observe?

If Pascal correctly diagnosed divertissement—if humans really do structure their lives around not confronting their condition—that observation stands regardless of whether his theological conclusions follow. The diagnosis can be useful even if the proposed cure is wrong.

VIII. The Invitation

The counter-tradition offers something the materialist framework cannot: permission to take your own experience seriously.

You have probably felt the things these thinkers describe. The restlessness that nothing satisfies. The despair that wears the mask of contentment. The spite that sabotages your own flourishing. The gravity that pulls you toward distraction, consumption, self-expansion.

The materialist framework tells you these feelings are illusions, chemical fluctuations, evolutionary hangovers to be managed with medication and cognitive-behavioral techniques. The counter-tradition says: these feelings are data. They are symptoms of something real. They point toward a dimension of human existence that your framework has defined out of reality.

You don’t have to believe in God to take these thinkers seriously. You just have to be willing to consider that the materialist map might be missing some territory. That the phenomena they describe might be real even if their explanations are incomplete.

The first step is simply to notice.

Notice the divertissement—the compulsive reaching for distraction. Don’t try to stop it yet. Just see it.

Notice the despair—the quiet sense that you’re not quite yourself, that you’re living by default. Don’t try to fix it. Just acknowledge it.

Notice the spite—the impulse to sabotage, to rebel, to prove you’re not a piano key. Don’t judge it. Just observe.

Notice the gravity—where your attention goes when you don’t direct it, how your soul moves when you let it fall.

These thinkers are offering you tools for seeing. The question is whether you’re willing to look.

IX. What Opens

If you begin to see what the counter-tradition saw, something shifts.

You stop trying to solve your restlessness with more activity. You stop trying to cure your despair with more success. You stop trying to optimize your way to meaning.

These strategies don’t work. They’ve never worked. Every civilization that has tried them has ended up where we are: materially rich, spiritually impoverished, wondering why all this progress hasn’t made anyone happier.

What opens is a different question: What if the longing is not a problem to be solved but a signal to be heeded?

The counter-tradition suggests that the human being is built with a kind of homing signal—a restlessness that is not pathological but vocational. The dissatisfaction is not a bug. It is the soul’s refusal to accept that bread alone is enough.

This does not mean the answer is traditional religion. It might be. It might not. But the first step is simply recognizing that there is a question—that the materialist framework, for all its power, leaves something essential unaddressed.

Pascal, Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Weil—they are not offering you beliefs to accept. They are offering you eyes to see what you already know but have been trained not to notice.

The void is real. The gravity is real. The longing is real.

What you do with this knowledge is up to you. But you cannot address a problem you refuse to see.

They saw it. They mapped it. They left records.

The rest is up to you.

Coda: The Wager Reformulated

Pascal’s famous wager—believe in God because you have nothing to lose—is usually dismissed as a cynical calculation. But there’s a deeper form of the wager that applies even if you never accept his theological conclusions:

What if taking your experience seriously opens possibilities that dismissing it forecloses?

If the materialist account is complete, and the restlessness is just neurons, and the longing is just evolution, then taking it seriously costs you nothing. You’ll discover that it’s nothing and move on.

But if the counter-tradition saw something real—if there is a dimension of human existence that materialism systematically misses—then dismissing your experience prematurely forecloses the possibility of discovering it.

The asymmetry runs the same direction Pascal noticed: on one side, you risk some intellectual embarrassment; on the other, you risk missing something essential.

You don’t have to leap anywhere. You just have to be willing to look.

The thinkers who resisted materialism before it became invisible are offering you their findings. They were not naive. They were not primitive. They understood the reduction and found it insufficient.

Perhaps they were wrong.

But they were wrong in ways that the data now suggests might have been right.

The least you owe them—the least you owe yourself—is an honest look.