The Employable Subject

Published 2025-12-19

Related posts:

I. The Question

Education is never merely transmission. Someone decides what counts as knowledge, what texts are worthy of study, what virtues children should absorb. That selection—that curation—is one of the most powerful tools available to any society. It shapes not just what people know, but what kind of people they become.

This essay asks a simple question: What kind of person does contemporary American education aim to produce? Not what it claims to produce—critical thinkers, lifelong learners, engaged citizens—but what it actually produces through its structures, incentives, and implicit assumptions.

The answer is troubling. The system produces what I call the employable subject: a person who has internalized a particular relationship to work, to self, and to the future—one characterized by self-exploitation mistaken for freedom, permanent anxiety experienced as motivation, and alienation from any sense of meaning beyond market value.

This is not conjecture. The mechanisms are visible in the curriculum itself—in what is taught, how it is taught, and what students are trained to do with their own minds and emotions. The philosophical diagnosis becomes concrete when we examine the actual practices of contemporary schooling.

II. The World We’re Being Prepared For

To understand what education produces, we must first understand the world it prepares people for. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman names our condition liquid modernity—a world where traditional markers of stability have dissolved. Long-term employment, fixed social roles, stable communities, predictable careers: these relics of “solid modernity” have given way to something more fluid and unstable.

In liquid modernity, individuals are expected to be flexible, mobile, and entrepreneurial. They must continuously adapt to changing conditions, reinvent themselves as markets shift, and bear personal responsibility for outcomes that are largely structurally determined. The stable job that previous generations could expect—work for a company for decades, retire with a pension—has become an anachronism. In its place: gig work, contract positions, frequent layoffs, and the imperative to continuously “upskill” and “reskill” in response to market demands.

This is the world for which education must prepare young people. And here we find the first clue to understanding contemporary curriculum: education is not training for any particular job. It is training a disposition toward work itself—the capacity to function in conditions of permanent instability while believing this instability is normal, natural, and even liberating.

III. The Official Framework: College and Career Readiness

The dominant framework in American K-12 education since 2010 has been the Common Core State Standards and their variants. The stated aim is unambiguous: to make students “college and career ready.” This phrase, repeated throughout educational policy documents, reveals the telos of the system. Education exists to produce workers and credential-seekers—and these two categories are understood as essentially the same thing.

The Southern Regional Education Board states plainly: “By 2025, two out of every three jobs will require some education beyond high school.” The Minnesota Department of Education defines a “sufficiently prepared student” as one who can “successfully navigate toward and adapt to an economically viable career.”

The curriculum is not designed to produce philosophers, citizens, contemplatives, or people who have discovered what makes their lives meaningful. It is designed to produce employees and college applicants.

But which employees? The workplace is enormously diverse—surgeons, plumbers, software engineers, baristas. How can a single system train for such varied outcomes?

The answer reveals everything. Consider what employers actually demand. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report lists the top skills employers seek: analytical thinking, resilience, flexibility, adaptability, leadership, creative thinking. LinkedIn data shows “adaptability” as the fastest-growing skill demand. Survey after survey reveals that employers prize “soft skills”—communication, collaboration, emotional intelligence—over technical competencies.

Notice what is absent: specific job skills. Employers do not primarily want people who can do particular tasks. They want people with particular dispositions: adaptable, resilient, flexible, collaborative. These are not skills for any job; they are skills for all jobs—or more precisely, for the condition of moving between jobs in a permanently unstable labor market.

They are survival skills for liquid modernity.

“Adaptability” means accepting that your job may disappear. “Resilience” means recovering when it does. “Emotional intelligence” means not becoming a problem when conditions are unstable. “Collaboration” means working smoothly with whoever you’re deployed alongside this quarter.

IV. The Mechanisms: How the Curriculum Produces Its Subjects

The philosophical claims become concrete when we examine the actual practices of contemporary schooling. The system does not merely state its goals; it enacts them through specific curricular mechanisms that train students to relate to themselves, their time, and their capacities in particular ways.

Social-Emotional Learning: The Self as Resource

Perhaps no development better illustrates the logic of contemporary education than the rise of Social-Emotional Learning (SEL). Nearly two-thirds of American schools now have formal SEL curricula, teaching children skills like “self-awareness,” “self-management,” “responsible decision-making,” and “relationship skills.”

The components sound unobjectionable. Who could oppose self-awareness? What’s wrong with learning to manage emotions? Isn’t it good to build relationship skills?

To see what’s problematic, we must look at what SEL replaces, what it does in practice, and what relationship to self it cultivates.

What SEL Replaces

Human beings have always needed to develop emotional maturity and social capacity. But for most of history, this development happened through lived experience embedded in particular communities: through family life and intergenerational relationships, through religious formation and moral tradition, through apprenticeship and mentorship, through friendship and heartbreak, through encountering great literature and art, through suffering and loss and recovery, through being held accountable by people who knew you and would continue to know you.

This formation was slow, contextual, and organic. It happened through life, not as preparation for it. And it was oriented toward substantive visions of human flourishing—what a good person is, what a good life looks like, what we owe each other.

SEL extracts social-emotional development from this context and relocates it to the classroom. It becomes curriculum: a set of competencies to be taught, practiced, and assessed like any other subject. The five CASEL competencies—self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, responsible decision-making—are broken into sub-skills, matched to grade-level standards, and measured through rubrics and assessments.

What is lost in this translation?

What SEL Looks Like in Practice

Consider what actually happens in SEL instruction. Students complete worksheets identifying their emotions using approved vocabulary (”I feel frustrated because...”). They practice “self-regulation strategies” like deep breathing and counting to ten. They role-play conflict resolution scenarios following prescribed steps. They fill out self-assessments rating their own competency levels. Teachers evaluate collaboration using rubrics that score “active listening” and “respectful disagreement.”

Morning meetings include “feelings check-ins” where students select emotion words from a chart. Posters display “zones of regulation”—green for calm and focused, yellow for frustrated or anxious, red for angry or terrified—and students learn to identify which zone they’re in and apply strategies to return to green. Classroom management systems reward students for demonstrating SEL competencies with points, badges, or privileges.

This is a very particular, and impoverished, model of emotional life. Emotions become things to be labeled, sorted, and regulated. The goal is not to feel more deeply but to manage more effectively. The rich, contextual, often ambiguous texture of emotional experience is flattened into a vocabulary list and a set of coping strategies.

A student who is angry about genuine injustice learns to “regulate” that anger rather than understand or act on it. A student who is anxious about a precarious future learns “mindfulness techniques” rather than examining whether the anxiety might be a reasonable response to unreasonable conditions. SEL systematically depoliticizes emotional life, treating all negative emotions as problems of individual regulation rather than potential signals about the world.

The Performance of Competence

Because SEL competencies are assessed, students learn to perform emotional competence rather than develop it. They learn what to say in a feelings check-in, how to appear on a collaboration rubric, which emotion words are appropriate for which situations. They become fluent in therapeutic language—they can identify their “triggers,” articulate their “needs,” describe their “growth areas”—while potentially remaining just as emotionally immature as before.

This is not speculation. Teachers report students who can perfectly articulate SEL concepts but show no transfer to actual behavior. The student who scores well on the “conflict resolution” assessment still bullies peers at recess. The student who identifies as “green zone” is suppressing emotions rather than processing them. The performance and the reality diverge.

The deeper problem is that the performance may prevent genuine development. When emotional life becomes another domain of assessment and achievement, students learn to relate to their own feelings as objects to be managed for external evaluation. The inner life becomes a performance for an audience. Authenticity becomes impossible when every emotional expression is potentially being scored.

The Self as Standing Reserve

The philosopher Martin Heidegger’s concept of Bestand—”standing reserve”—illuminates what is ultimately at stake. Heidegger argued that modern technology reveals everything as resources standing by for exploitation. The forest becomes timber inventory; the river becomes hydroelectric potential; the land becomes real estate. Nothing is allowed to simply be; everything must be revealed as available for use.

SEL extends this logic to the inner life. Consider the CASEL framework’s explicit connection to “college and career readiness.” The organization’s materials state that SEL skills “are essential for success in school, work, and life” and that they “prepare students to succeed in careers.” Employers consistently rank “emotional intelligence” among the top skills they seek. SEL is not hidden about its instrumental purpose: your emotional life matters because it affects your productivity and employability.

This is what it means for the self to become standing reserve. Emotions are not experiences that constitute a human life—joy that illuminates, grief that deepens, anger that motivates, love that connects. They are resources to be optimized for deployment. The capacity for feeling becomes human capital. The soul becomes infrastructure.

The contrast with traditional formation is stark. When a student encounters Lear’s anguish on the heath, or Anna Karenina’s desperation, or Achilles’ grief for Patroclus, something may happen that cannot be measured or assessed. The encounter may deepen the student’s capacity for feeling, expand their moral imagination, connect them to the long human experience of suffering and transcendence. This is formation through exposure to greatness, not training in competencies.

SEL replaces this with worksheets.

The Reasonable Becomes Insidious

Each component of SEL, examined in isolation, seems benign. In context, something else emerges:

Self-awareness—know your strengths and limitations—becomes perpetual self-monitoring: seeing yourself always from the outside, as a portfolio of assets and liabilities to be managed. The examined life becomes the audited life.

Self-management—regulate emotions and behaviors—becomes the internalization of control: no longer needing external discipline because you discipline yourself. The achievement-subject needs no overseer; they surveil themselves.

Social awareness—understand others’ perspectives—becomes a technique for smooth collaboration rather than genuine empathy: understanding others instrumentally so you can work with anyone, not because others matter intrinsically.

Relationship skills—build and maintain connections—makes relationships instrumental: “networking” in everything but name. The friend becomes a contact; the community becomes a professional network.

Responsible decision-making—make constructive choices—defines “constructive” implicitly by outcomes: choices that advance your goals, protect your interests, optimize your position. The framework has no space for decisions made from duty, loyalty, love, or principle regardless of outcome.

The genius of SEL is that it appropriates genuine human needs—for emotional support, for community, for meaning—and offers a thin, instrumentalized substitute. Students do need help navigating emotions, building relationships, making decisions. They need this desperately, perhaps more than ever. But what they need is formation in the context of genuine community, oriented toward substantive visions of human flourishing. What they get is competency training oriented toward career readiness.

The reasonable components, assembled into a system and oriented toward employability, produce something that is not reasonable at all: the colonization of the inner life by the logic of optimization.

Growth Mindset: Infinite Improvability

The “growth mindset” framework, derived from Carol Dweck’s research and now ubiquitous in American schools, teaches students that abilities are not fixed but can be developed through effort and practice. The implication, repeated endlessly in classroom posters and teacher exhortations: you can always improve. Failure is just feedback. Setback is opportunity.

On its face, this seems benign—even liberating. But consider its function within the larger system. If abilities are infinitely improvable, then any failure to improve is a failure of effort. The student who does not succeed has simply not worked hard enough, not adopted the right mindset, not put in sufficient practice. Structural explanations—inadequate resources, unfair systems, simple bad luck—are foreclosed by the ideology of infinite improvability.

Growth mindset trains students to take personal responsibility for outcomes that may be structurally determined. It prepares them for a labor market that will constantly demand they upskill, reskill, and reinvent themselves—and it teaches them that any failure to do so reflects a deficiency of character rather than a deficiency of opportunity.

The message is: you are never finished. You can always be better. Your current self is merely raw material for your future self. This is the temporal structure of liquid modernity internalized as psychology.

Standardized Testing: Training Hyperattention

The regime of standardized testing—from state assessments to the SAT, from AP exams to the endless benchmark assessments that now structure the school year—trains a particular mode of attention.

The Korean-German philosopher Byung-Chul Han distinguishes between “deep attention” and “hyperattention.” Deep attention is the sustained focus required for complex thought—the capacity to dwell with a difficult text, to follow an argument through its complications, to hold a problem in mind long enough to think it through. Hyperattention is scattered, multitasking awareness—the capacity to quickly scan, extract information, move on.

“Culture presumes an environment in which deep attention is possible,” Han writes. But standardized testing cultivates hyperattention. Students learn to scan passages for relevant information, eliminate wrong answers, manage time across dozens of questions. They learn to optimize for the test rather than to think.

The structure of the school day reinforces this training. Subjects are fragmented into 45-minute periods. Attention is constantly interrupted by bells, transitions, announcements. The day is structured around the schedule, not around the demands of thought. No text is given more time than the period allows. No problem is explored beyond what the curriculum specifies.

This is not a failure of the system but its function. Hyperattention is precisely what liquid modernity requires. The worker who can quickly adapt, rapidly process new information, and efficiently move between tasks is more valuable than the worker capable of deep concentration. The test trains the worker.

The College Application: Self-Commodification as Curriculum

The college application process has become a shadow curriculum, structuring student behavior from middle school onward. Students learn to think strategically about how every activity will “look” on an application. They curate experiences for their resume value. They craft personal narratives designed to appeal to admissions committees.

The Common Application asks students to write essays about their identity, their challenges, their passions. These essays are exercises in self-commodification. The student must produce a compelling story of self—a personal brand—that will differentiate them in a competitive market. Authenticity itself becomes a performance, a product to be optimized for the college marketplace.

The message is clear: you are not a person but a portfolio. Your experiences are not intrinsically meaningful but instrumentally valuable. Your very identity is something to be crafted, packaged, and sold.

Students learn this lesson well before they actually apply to college. The logic of the application colonizes extracurricular activities (join clubs that will impress admissions), summer experiences (find internships or service trips with resume value), and even friendships (network with people who can provide recommendations). Life becomes preparation for the application; the application becomes preparation for the career; the career becomes... what?

Project-Based Learning and “Real-World” Preparation

Contemporary pedagogy increasingly emphasizes “project-based learning,” “authentic assessment,” and “real-world application.” Students work in teams to produce deliverables. They present to audiences. They receive feedback. The classroom mimics the workplace.

Again, this seems sensible—even progressive. Why shouldn’t learning connect to the real world? But notice what “real world” means in practice: it means the workplace. The “authentic” context is always professional. The skills being developed are always marketable.

This is the hidden curriculum: the only “real” world is the world of work. The activities that constitute a human life—contemplation, worship, play, love, political participation, creative expression without audience—are not “real” because they are not monetizable. The student learns that meaning comes from production, value from market recognition, significance from professional achievement.

The Temporal Structure: No Sabbath

Perhaps the most pervasive mechanism is invisible because it is so total: the structure of time itself.

The contemporary student’s schedule leaves no unstructured time. School runs from 8 to 3. Then extracurriculars until 5 or 6. Then homework until 10 or 11. Weekends are consumed by test prep, college visits, resume-building activities. Summers are for internships, programs, enrichment.

There is no sabbath—no time when the work of self-optimization is set aside. There is no leisure in the classical sense: schole, the Greek word from which we get “school,” originally meant time free from labor, time for cultivation of self and mind. Contemporary schooling has evacuated schole from school.

The student learns that time is a resource to be maximized. Unproductive time is wasted time. Rest is justified only as recovery for more production. The structure of the school day and year teaches this lesson more powerfully than any explicit curriculum could.

V. The Ideal Product

These mechanisms—SEL, growth mindset, standardized testing, college applications, project-based learning, the temporal structure of schooling—work together to produce a particular kind of subject. Drawing on several contemporary philosophers, we can sketch a composite portrait.

The Self-Exploiting Achiever

Byung-Chul Han argues in The Burnout Society that we have shifted from a “disciplinary society”—Foucault’s world of prisons, factories, and explicit prohibitions—to an “achievement society” governed by the positive injunction to perform, optimize, and achieve.

The characteristic subject of this new regime is not the “obedience-subject” who follows external commands, but the “achievement-subject” who has internalized the imperative to maximize performance. As Han puts it: “They are entrepreneurs of themselves.”

The achievement-subject does not need external compulsion; they exploit themselves voluntarily. “Achievement society is the society of self-exploitation. The achievement-subject exploits itself until it burns out.”

The genius of this system—from the perspective of capital—is that it is more efficient than external coercion. “Auto-exploitation is more efficient than allo-exploitation because a deceptive feeling of freedom accompanies it.” The worker who drives herself to exhaustion believes she is exercising agency, pursuing her dreams, building her brand. She does not recognize that she has internalized a logic of relentless optimization that serves interests other than her own.

The mechanisms we have examined produce exactly this subject. SEL teaches self-management as self-exploitation. Growth mindset teaches that any failure is a failure of effort. The testing regime teaches optimization as a mode of being. The college application teaches self-commodification as identity. The temporal structure teaches that rest is waste.

The epidemic of student anxiety, depression, and burnout is not a bug in this system but a feature—the predictable pathology of subjects who have been taught that their value lies in their performance.

The Cynical Performer

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek offers a complementary diagnosis. Building on Peter Sloterdijk, Žižek argues that contemporary ideology operates not through false consciousness but through “ideological cynicism.” The formula is no longer Marx’s “they do not know it, but they are doing it” but rather “they know it, but they are doing it anyway.”

Today’s subjects are not naive believers in meritocracy, the neutrality of education, or the value of credentials. They are cynics who see through these ideologies yet continue to act as if they believed. Students know that college rankings are arbitrary, that credential inflation has made degrees less valuable, that the system is rigged in favor of the wealthy. They know it—and they apply to elite colleges anyway, accumulate credentials anyway, play the game anyway.

This cynical distance does not liberate subjects from ideology but represents its most advanced form. The appearance of “post-ideological” pragmatism—”I don’t believe any of this, I’m just doing what I need to do”—is itself ideological, because it leaves the underlying structure intact.

What education produces is not believers but performers—subjects who maintain an ironic distance from their own actions while continuing to perform those actions. The college essay is a perfect example: students craft narratives of authentic passion while knowing the exercise is performative, and admissions officers evaluate “authenticity” while knowing it is performed. Everyone knows; no one believes; the system continues.

This is the perfect disposition for liquid modernity: flexible, adaptive, capable of believing and disbelieving simultaneously, never so committed to any value that they cannot pivot when the market demands it.

The Mimetic Competitor

The French anthropologist René Girard offers a third lens: mimetic desire. For Girard, human beings do not know what they want autonomously. They learn what to want by imitating the desires of others.

When models and imitators occupy the same competitive space, mimetic desire becomes mimetic rivalry. The closer we are to our models, the more we become competitors for the same objects.

American education is a mimetic rivalry machine of unprecedented intensity. Students compete for the same grades, the same rankings, the same college admissions slots. Social media has intensified this dynamic by making everyone’s achievements visible to everyone else. Every peer’s internship, every classmate’s acceptance letter, every friend’s accomplishment is immediately known and immediately becomes the standard against which one measures oneself.

The anxiety and depression endemic to American students is not primarily about workload but about rivalry. The system teaches children that they are competing with all other children for scarce goods—admission slots, opportunities, recognition. Since these goods are perceived as zero-sum, every peer is a potential rival.

The curriculum does not need to explicitly teach competition; it structures social reality so that competition becomes inevitable. When everyone is ranked against everyone else on common metrics, mimetic rivalry is not a choice but a necessity.

VI. The Employable Subject

Synthesizing these analyses, we arrive at the employable subject—the type of person the system is optimized to produce. This subject has internalized several core beliefs:

Self-responsibilization. The employable subject believes that if they cannot find work, the problem is them—insufficient skills, wrong degree, inadequate networking, not enough “grit.” Structural explanations (there are no jobs, wages have stagnated, the economy is rigged) are reframed as personal failures requiring personal solutions. Growth mindset has taught them that obstacles are opportunities; SEL has taught them to manage their emotional response to disappointment; the testing regime has taught them that scores reflect preparation. Everything conspires to locate responsibility in the self.

Permanent availability. The employable subject never stops working on their employability. Even when employed, they must continuously upskill, reskill, network, build their personal brand. The concept of being “done” with education—of having acquired sufficient preparation for adult life—has disappeared. Growth mindset has taught them that improvement is always possible; the temporal structure of schooling has taught them that unproductive time is wasted time. There is no sabbath, no rest, no completion.

Acceptance of precarity as normal. Gig work, contract positions, “pivoting,” layoffs, career changes—these are not failures of the system but features requiring adaptation. The employable subject does not expect job security; they expect to be hired, fired, and redeployed as market conditions shift. Flexibility, after all, is what they have been trained for. The very concept of a “career”—a stable trajectory through an occupation—gives way to a series of contingent positions requiring perpetual reinvention.

Human capital as self-concept. The employable subject understands themselves as human capital to be invested. Education is not about becoming a certain kind of person; it is about increasing one’s market value. Every experience is evaluated for its contribution to the resume. Every skill is assessed for its economic return. The self becomes a portfolio to be optimized. SEL teaches them to manage this portfolio’s emotional dimensions; the college application teaches them to market it; standardized testing teaches them to measure it.

Here is the cruel irony: an individual can be a responsible investor in every respect, yet end up jettisoned by uneven and unpredictable twists in the labor market. You can do everything right—get the degree, build the skills, network relentlessly—and still be unemployed because there are no jobs, or because the jobs pay poverty wages, or because an algorithm decided your resume lacked the right keywords. The employable subject takes personal responsibility for outcomes that are structurally determined.

This explains the mental health crisis among students and young workers. The system promises that self-investment will yield returns, but the returns are not guaranteed. When they fail to materialize, the employable subject has no one to blame but themselves.

VII. The Alienation at the Core

What unites all these descriptions is a single phenomenon: alienation.

The employable subject is alienated from their own desires—they want what everyone else wants, competing for prizes they never stopped to question. They are alienated from their own emotions—feelings are resources to be managed rather than experiences to be lived. They are alienated from their own labor—work is not a means of self-expression or contribution but a performance to be optimized for external metrics. They are alienated from community—every peer is a potential rival, every relationship a networking opportunity. They are alienated from time—there is no sabbath, no leisure, no moment when the work of self-optimization is complete.

Heidegger’s concept of standing reserve illuminates the depth of this alienation. When the self becomes Bestand—resource on standby for exploitation—something fundamental has been lost. The human being is no longer a being with inherent dignity who might ask about the meaning of existence. They are raw material to be processed, optimized, deployed.

Most insidiously, the employable subject is alienated from this alienation. They experience their condition as freedom. The absence of external commands feels like autonomy. The imperative to optimize feels like ambition. The anxiety of competition feels like motivation. The precarity feels like flexibility.

Han’s phrase captures it precisely: “a deceptive feeling of freedom accompanies it.” The employable subject believes they are choosing their life when they are in fact being shaped by forces they cannot see because those forces have been internalized so completely.

The curriculum does its work invisibly. No one tells students that they are being trained for self-exploitation. The message is always positive: develop yourself, realize your potential, build your future. The coercion is hidden inside the empowerment. The exploitation is disguised as opportunity.

VIII. What Was Lost

To see what contemporary education lacks, it helps to contrast it with older models—not to romanticize them, but to recover a sense of possibility.

Until the late nineteenth century, American higher education was built around the classical curriculum: Greek and Latin languages, ancient literature and history, rhetoric, logic, and moral philosophy. The Yale Report of 1828 defended this curriculum as “the most effectual discipline of the mental faculties.”

The classical curriculum aimed to produce something quite different from “college and career readiness.” It aimed to produce liberally educated people—the Latin liberalis meaning “appropriate for free people.” The assumption was that citizens who would participate in public life needed capacities that transcended any particular vocation: the ability to speak and write persuasively, to reason logically, to understand historical precedent, to make moral judgments.

The structure differed profoundly from contemporary schooling. Students translated texts slowly—word by word, phrase by phrase—developing what Han would call “deep attention.” They encountered the same texts repeatedly across years, developing layers of understanding rather than racing through content. The content itself transmitted a particular moral vocabulary. Students encountered Socrates accepting death rather than abandoning philosophy, Cincinnatus leaving his plow to save Rome then returning when the crisis passed.

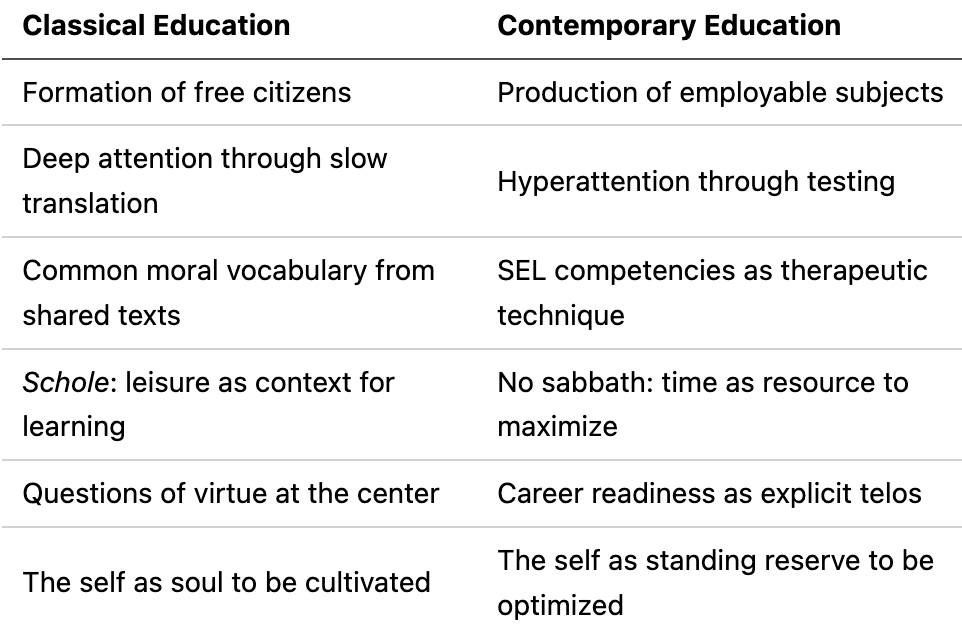

The contrast is stark:

We should not romanticize the classical system. The classically educated elite built empires, maintained slavery, and subordinated women. The classical curriculum often functioned less as intellectual formation than as social gatekeeping—knowledge of Greek and Latin marked one as a gentleman, signaling membership in the ruling class rather than depth of understanding.

But something real was lost. Not a golden age—which probably never existed as advertised—but the possibility that education might aim at something other than economic productivity.

The classical curriculum, whatever its failures in practice, at least posed the right questions: What should a free person know? What virtues should education cultivate? What texts are worthy of deep attention across generations? These questions have not been answered by contemporary education; they have been abandoned. In their place we find only: What skills does the market demand? What credentials lead to employment? How can we measure learning outcomes?

IX. The Alternative

Is there another way? Can education be life-affirming and meaning-affirming rather than merely market-serving?

The first step is simply to see the current system for what it is. The employable subject cannot recognize their condition because it feels like freedom. Naming the alienation—identifying the mechanisms that produce it—is the beginning of liberation.

The mechanisms must be named specifically:

-

SEL is not neutral life skills; it is training for self-exploitation.

-

Growth mindset is not empowerment; it is the internalization of infinite demands.

-

Standardized testing is not assessment; it is the cultivation of hyperattention.

-

College applications are not self-expression; they are self-commodification.

-

The absence of unstructured time is not rigor; it is the colonization of leisure.

The second step is to recover the questions that contemporary education has abandoned. What is education for? Not in terms of economic outcomes, but in terms of human flourishing. What kind of person should education help someone become? Not what kind of worker, but what kind of person—what capacities, what virtues, what relationship to self and others and world?

These questions admit of many answers. But any answer worth considering will share certain features:

Education as formation, not optimization. The goal is not to maximize some metric—test scores, earnings potential, resume items—but to help a person become more fully themselves. This requires attention to the particular person, not generic “skills” applicable to anyone. It means treating students as beings with inherent dignity, not as standing reserve to be processed.

Deep attention over hyperattention. Han contrasts the scattered, multitasking awareness suitable for processing endless stimuli with the sustained focus required for genuine thought. “Culture presumes an environment in which deep attention is possible.” An education worthy of the name cultivates the capacity to dwell with difficulty, to read slowly, to think through problems rather than scan for answers.

Emotions as experiences, not resources. Against SEL’s managerial approach, education could help students live their emotional lives rather than manage them. This means encountering art, literature, and music that evokes genuine feeling—not as “social-emotional learning” with measurable competencies, but as encounters with beauty, tragedy, and the full range of human experience.

Intrinsic meaning over instrumental value. The employable subject evaluates every experience by its contribution to employability. But some things are worth doing for their own sake—reading poetry, learning history, studying mathematics, making music, contemplating nature. An education that treats everything as instrumental to something else teaches people that nothing has intrinsic value.

Community over competition. The mimetic rivalry machine structures every peer as a potential competitor. But learning is better understood as a collaborative endeavor—we learn from each other, we learn with each other. Education can cultivate solidarity rather than rivalry.

Sabbath. There must be time that is not productive—time for rest, for play, for contemplation, for simply being rather than endlessly becoming. The temporal structure of education must include genuine leisure, not as recovery for more production, but as intrinsically valuable.

Questions of meaning at the center. The classical curriculum, for all its faults, placed questions of virtue and the good life at the center of education. Contemporary education has evacuated these questions, treating them as matters of private preference rather than public concern. But meaning is not optional. Human beings need to understand their lives as meaningful. An education that ignores this need produces people who are productive but empty.

X. Conclusion

Every educational system produces a certain kind of person. The Confucian examination system produced scholar-officials who thought in Confucian categories. The French Third Republic produced citizens who knew Lavisse’s national narrative. Contemporary American education produces the employable subject—adaptive, resilient, anxious, alienated, and convinced that this is freedom.

The mechanisms are now visible: SEL that trains self-management as self-exploitation; growth mindset that forecloses structural critique; testing regimes that cultivate hyperattention; college applications that demand self-commodification; temporal structures that eliminate sabbath. The philosophical diagnosis—Han’s achievement-subject, Žižek’s cynical performer, Girard’s mimetic competitor, Heidegger’s standing reserve—finds concrete expression in the curriculum.

The question is not whether education shapes minds—of course it does. The question is whether it shapes them toward good ends by good means. The system we have produces effective workers at the cost of widespread psychological pathology. It produces flexible performers who can adapt to any condition except the condition of asking whether the system itself makes sense. It produces people who have optimized themselves for a labor market that offers them little loyalty in return.

There is another possibility. Education could aim at human flourishing rather than employability. It could cultivate deep attention rather than hyperattention. It could treat emotions as experiences rather than resources. It could ask what a life means rather than what it earns. It could form persons rather than optimize human capital.

This would require changing not just curricula but the entire structure of incentives that shapes education—the testing regimes, the credential requirements, the college admissions processes, the labor market that makes these pressures feel necessary. It would require, in short, a different world.

But imagining that different world is itself a form of resistance. The employable subject cannot imagine alternatives because they have internalized the premise that this system cannot be otherwise. To see that it can be otherwise—that education could serve life rather than merely preparing people to sell their labor—is the first step toward making it so.

The system produces what it produces because we let it. The question is whether we will continue to let it—or whether we will demand an education worthy of free people.