The Amplifier Theory of Human Hierarchy

Published 2026-01-07Human beings possess competing dispositions: a drive toward dominance and a drive to resist domination by others. In a “fair fight” (without external leverage) the collective can suppress would-be dominators, producing egalitarian social arrangements. This is not utopian speculation; it describes the documented reality of immediate-return hunter-gatherer societies across multiple continents. However, when environmental, technological, or social conditions provide amplifiers (mechanisms that extend individual power beyond what collective resistance can counter) hierarchy emerges and becomes self-reinforcing. This essay argues that the near-universal pattern of stratification and exploitation in human history is caused by near-universally available amplifiers. The historical record, examined through this lens, reveals that the same species produces radical egalitarianism and brutal hierarchy depending on amplifier availability.

I. The Puzzle: One Species, Two Outcomes

Consider two human societies, separated by geography but connected by common ancestry:

The Ju/’hoansi of the Kalahari: No formal leadership. No wealth accumulation. A successful hunter is mocked for his kill—“You mean you dragged us all the way out here for this scrawny thing?”—lest he imagine himself superior. Anyone can demand anything from anyone else, and refusal is shameful. Anthropologist Richard Lee called them “fiercely egalitarian.”

The Tlingit of the Pacific Northwest: Hereditary nobility. Elaborate ranking systems. Slaves comprising perhaps 15-25% of some communities. Competitive potlatch ceremonies where chiefs destroyed wealth to demonstrate superiority. A society that anthropologist Rosita Worl, herself Tlingit, acknowledged was built on slave labor.

Both societies were hunter-gatherers. Neither practiced agriculture. Neither built cities or empires. Yet one maintained radical equality while the other institutionalized hereditary bondage.

The standard explanations fail:

-

“Civilization causes hierarchy”: But the Tlingit weren’t civilized in any conventional sense—no writing, no cities, no agriculture.

-

“Agriculture causes hierarchy”: But the Tlingit were foragers.

-

“Some cultures are just more hierarchical”: But this explains nothing; it merely redescribes the phenomenon.

-

“Human nature is hierarchical”: But the Ju/’hoansi are also human.

What actually distinguishes these cases?

II. The Amplifier Model

The Baseline Condition

Anthropologist Christopher Boehm, synthesizing decades of research on both human foragers and our primate relatives, argued that humans share with chimpanzees and bonobos a disposition toward dominance but also, critically, a disposition toward resisting domination by others. We are neither pure despots nor pure egalitarians by nature. We are both.

In small groups without external leverage, these dispositions produce what Boehm called a “reverse dominance hierarchy”: the collective gangs up on would-be dominators. Any individual attempting to claim superior status faces ridicule, ostracism, and potentially violence from the coalition of everyone else. The costs of attempted dominance exceed the benefits.

This is not passive equality. It is actively maintained equality. Egalitarianism as achievement, not default.

The Amplifier Effect

An amplifier is anything that extends an individual’s (or coalition’s) power beyond what collective resistance can counter. Amplifiers allow:

-

Accumulation faster than redistribution: Resources can be gathered and defended before the group can demand-share them away

-

Defense against collective sanction: The amplified individual can resist or punish those who would mock, ostracize, or attack them

-

Conversion of resources into durable power: Wealth becomes followers; followers become enforcers; enforcers protect wealth

Once a sufficient amplifier advantage exists, power becomes self-reinforcing. The amplified individual uses their advantage to acquire more amplifiers, widening the gap until collective resistance becomes futile.

Taxonomy of Amplifiers

Geographic Amplifiers: Natural features that concentrate resources and provide defensive advantages

-

Salmon runs (Northwest Coast)

-

Irrigation chokepoints (Mesopotamia, Egypt, China)

-

Mountain passes and harbors (Greek city-states)

-

Navigable rivers connecting agricultural hinterlands (all major empires)

Technological Amplifiers: Tools that store value or multiply force

-

Granaries and storage facilities (extend power through time)

-

Weapons asymmetries (bronze vs. stone, guns vs. spears)

-

Fortifications (defensive force multiplication)

-

Writing and record-keeping (administrative coordination at scale)

-

Transportation (horses, ships—project power across space)

Social Amplifiers: Relationship structures that convert resources into obligation

-

Debt and credit systems

-

Patron-client networks

-

Kinship manipulation (marriage alliances, adoption)

-

Retainer and servant relationships

Ideological Amplifiers: Belief systems that make hierarchy appear natural or sacred

-

Divine kingship

-

Caste cosmologies

-

Ancestor cults linking legitimacy to lineage

-

Religious doctrines sanctifying submission

Informational Amplifiers: Knowledge asymmetries enabling coordination advantages

-

Literacy monopolies (priestly classes)

-

Census and tax records

-

Legal codes accessible only to elites

-

Specialized technical knowledge

Critically, amplifiers compound. Geographic advantages enable technological development; technology enables social complexity; social structures generate ideological justification; ideology legitimizes the entire system and suppresses resistance.

III. The Historical Evidence

A. Geographic Amplifiers: The Case of the Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest provides a natural experiment. Along the same coastline, with the same basic foraging technology, societies ranged from relatively egalitarian to rigidly stratified. What predicted the difference?

A 2021 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences examined 89 hunter-gatherer societies along the Pacific Coast from Alaska to California. The researchers tested multiple hypotheses: population pressure, warfare intensity, resource abundance. Only one variable robustly predicted institutionalized hierarchy, including slavery: the presence of defensible, clumped resources that could be monopolized.

Salmon runs were the paradigmatic case. Where salmon congregated at predictable times in defensible locations (river mouths, waterfalls) the groups controlling those locations developed hereditary nobility and slave systems. Where resources were more dispersed, societies remained more egalitarian.

The Tlingit controlled prime salmon fishing sites as clan property. These sites were:

-

Concentrated: Salmon funneled through specific geographic chokepoints

-

Predictable: Runs occurred at known times each year

-

Storable: Salmon could be smoked and preserved for winter

-

Defensible: Physical control of the site meant control of the resource

This created the conditions for accumulation. A clan controlling a rich site could produce surplus beyond immediate consumption. That surplus could feed non-producing dependents, who then processed more fish, enabling more accumulation.

The system became self-reinforcing. Wealthy clans could mount more raids, capture more slaves, process more salmon, and widen their advantage. Slavery among the Tlingit was practiced extensively until it was outlawed by the United States Government.

Anthropologist David Graeber noted the contrast: “The social organization of Northwest Coast foragers bears comparison with that of courtly estates in medieval Europe, where a leisured class of nobles achieved status through hereditary ranking, competitive banquets, dazzling aesthetic displays, and the retention of household slaves captured in war.”

Along the Pacific Northwest: The same species. The same basic subsistence mode. Radically different outcomes, determined by geographic amplifiers.

B. Technological Amplifiers: Storage and the Neolithic Transition

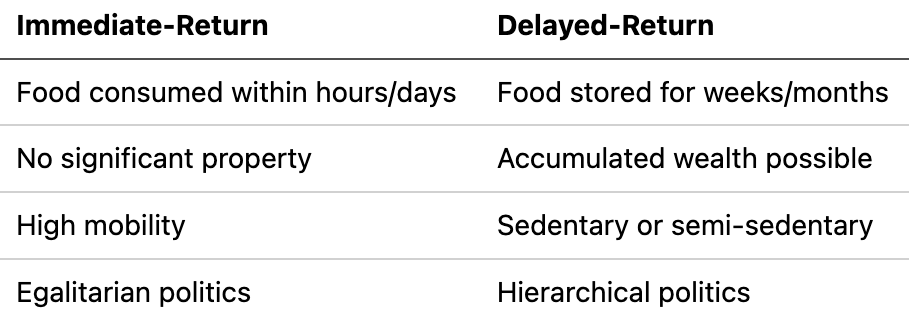

James Woodburn’s distinction between “immediate-return” and “delayed-return” societies identifies storage as the crucial technological threshold:

Immediate-return foragers (e.g., the Hadza, Ju/’hoansi, Mbuti) consume resources as they acquire them. There is nothing to accumulate, nothing to defend, nothing that could amplify one person’s power over another. Mobility means that anyone facing domination can simply leave.

Delayed-return systems—whether the salmon storage of the Northwest Coast or the grain storage of early agricultural societies—create the possibility of accumulation. Stored resources represent crystallized labor that can be guarded, defended, and converted into power.

The archaeological record confirms the pattern. The Natufian culture of the Levant (c. 15,000-11,500 years ago) shows the earliest evidence of sedentism and intensive plant exploitation in the Near East. And it shows corresponding evidence of social differentiation: elaborate burials for some individuals, simpler interments for others. The transition from mobile foraging to sedentary resource management correlates with the emergence of status hierarchy.

The granary is a technological amplifier. It allows:

-

Storage of surplus beyond immediate needs

-

Defense of that surplus against redistribution demands

-

Feeding of non-productive dependents (servants, soldiers, priests)

-

Survival through scarcity that eliminates the unprovisioned

Control of stored grain became the foundation of early state power across Mesopotamia, Egypt, China, and Mesoamerica. The temple and palace complexes of ancient cities were, at their core, fortified granaries with elaborate ideological justification.

C. Social Amplifiers: Debt and Dependency

Beyond geography and technology, social institutions themselves become amplifiers. Debt is among the most powerful.

The Code of Hammurabi (c. 1754 BCE) codified debt bondage in Babylonian law. A free person unable to repay debts could be sold into slavery, or could sell family members. The code regulates the terms:

“If a man be in debt and sell his wife, son, or daughter, or bind them over to service, for three years they shall work in the house of their purchaser or master; in the fourth year they shall be given their freedom.”

This three-year limit suggests the practice was common enough to require regulation. Debt converted economic misfortune into bondage—and bondage produced labor that enriched creditors, enabling them to extend more debt.

In West Africa, the institution of “pawning” operated similarly. Individuals could pledge themselves or family members as security for loans. Critically, “the services rendered by pawns did not apply towards the liquidation of the debt”—the labor was interest, not principal repayment. A pawn could work indefinitely without reducing their obligation.

Debt as amplifier creates self-reinforcing inequality:

-

Economic shock (drought, illness, failed harvest) forces borrowing

-

Borrower becomes dependent on creditor

-

Creditor extracts labor/service that increases their wealth

-

Increased wealth enables more lending

-

More debtors become dependents

-

Creditor’s power grows; collective resistance becomes impossible

The pattern appears across cultures: debt bondage in Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, India, Africa, and pre-Columbian Americas. It is not a cultural peculiarity but an emergent property of lending in societies with weak collective constraints on creditor power.

D. Ideological Amplifiers: Making Hierarchy Sacred

The most durable amplifier is belief itself. When the dominated internalize the legitimacy of their domination (go read The Employable Subject to see how we internalize this today!), external enforcement becomes less necessary. The Manusmriti represents the fullest development of ideological amplification.

The text grounds caste hierarchy in cosmic creation:

“For the welfare of humanity the supreme creator Brahma gave birth to the Brahmins from his mouth, the Kshatriyas from his shoulders, the Vaishyas from his thighs and Shudras from his feet.” (Manu I.31)

The body metaphor is precise: the head thinks and speaks; the arms fight; the thighs support; the feet are trodden upon. Hierarchy is not a social arrangement but an anatomical fact of the universe.

The Manusmriti then specifies that this hierarchy is ontological. Inherent in the nature of being:

“A Shudra, though emancipated by his master, is not released from servitude; since that is innate in him, who can set him free from it?” (Manu VIII.414)

Not even the master can free the Shudra, because servitude is not a social status but a metaphysical property. The text recommends that Shudra names “express something contemptible” (Manu II.31), linguistic markers reinforcing degradation from birth.

This is amplification through internalized belief. The Brahmin need not personally enforce hierarchy; the Shudra enforces it upon himself, believing his position reflects cosmic truth. Resistance becomes not merely dangerous but cosmically wrong—a violation of dharma that will produce karmic consequences across lifetimes.

Compare the Tokugawa status system in Japan. The Eta (穢多, “abundance of filth”) and Hinin (非人, “non-human”) were outcaste groups assigned to occupations involving death and pollution. The terminology itself—”non-human”—denies the very category under which rights might be claimed.

An 1880 Meiji Ministry of Justice handbook described the former outcastes as “the lowliest of all the people, almost resembling animals.” A legend held that killing seven Eta equaled the crime of killing one person. The ideology quantified dehumanization.

These ideological systems did not merely justify hierarchy—they constituted it. Once internalized, they made hierarchy self-maintaining without continuous violence. The Brahmin’s power was amplified by the Shudra’s belief.

E. Compounding Amplifiers: The Full System

In practice, amplifiers compound. The great agrarian empires combined all types:

Mesopotamia:

-

Geographic: Tigris-Euphrates floodplain enabling irrigation agriculture

-

Technological: Granaries, bronze weapons, writing, fortified cities

-

Social: Debt bondage, temple-palace dependency systems

-

Ideological: Divine kingship, cosmic order reflecting social order

-

Informational: Cuneiform literacy monopolized by scribal class

Each amplifier enabled and reinforced the others. Irrigation agriculture (geographic + technological) produced surplus; surplus fed specialists (social); specialists developed writing (informational); writing enabled legal codification (ideological + informational); law codified debt bondage (social); debt bondage produced dependent labor (social + technological); dependent labor expanded irrigation (geographic).

The system was not designed; it emerged from the interaction of amplifiers, each creating conditions for more amplification.

IV. The Counter-Evidence That Proves the Rule

Egalitarian Societies as Controlled Experiments

If the amplifier model is correct, societies lacking amplifiers should remain egalitarian—and they do.

The Ju/’hoansi (!Kung San) of the Kalahari demonstrate egalitarianism as active achievement. Their environment provides no defensible resource concentrations. Water holes are dispersed. Game animals range widely. Plant foods must be gathered daily. Mobility is essential.

Under these conditions, the Ju/’hoansi developed sophisticated anti-hierarchical mechanisms:

Demand sharing: Anyone can ask anyone for anything, and refusal is shameful. This prevents accumulation by ensuring that any surplus is immediately redistributed.

Insulting the meat: A successful hunter’s kill is publicly disparaged. Richard Lee recorded a Ju/’hoansi man’s explanation:

“When a young man kills much meat, he comes to think of himself as a chief or a big man, and he thinks of the rest of us as his servants or inferiors. We can’t accept this... so we always speak of his meat as worthless. This way we cool his heart and make him gentle.”

Distributed processing: A hunter never distributes his own kill. The arrows used in hunting are frequently borrowed, and the “owner” of the arrow that made the kill controls distribution, divorcing success from the social power of giving.

Mobility as exit: Anyone facing domination can leave. Groups are fluid; composition changes seasonally. Without fixed assets to defend, there is nothing tying a person to an oppressive situation.

These mechanisms make sense only as responses to the ever-present possibility of dominance attempts. The Ju/’hoansi are not egalitarian because they lack dominance impulses; they are egalitarian because they actively suppress those impulses in an environment where suppression is possible.

The Hadza Parallel

The Hadza of Tanzania, studied intensively by James Woodburn, display similar patterns. They practice “immediate-return” foraging: food is acquired and consumed within hours or days. Woodburn observed:

“Hadza men and women obtain food for themselves individually, or in pairs, or as members of small foraging groups. Individuals retain control over the food they obtain; no-one has claims to any portion.”

Yet this individual control is immediately constrained by:

“Strong social pressure to share food, especially meat, and a person who hoards is subject to criticism and to having food demanded.”

The Hadza maintain egalitarianism through the same mechanisms as the Ju/’hoansi: demand sharing, ridicule of self-aggrandizement, and mobility. And critically, they occupy an environment with dispersed, non-storable resources that provide no amplifier opportunities.

The BaYaka: Egalitarianism Through Ritual

Among the BaYaka (Mbendjele) of the Congo Basin, anthropologist Jerome Lewis documented how gender relations and ritual practice enforce equality. The institution of moadjo—theatrical mimicry—allows women to publicly ridicule any behavior deemed unacceptable:

“Senior women exercise a special privilege, seeing it as their enjoyable role to use moadjo to bring down anyone who seems to be getting too boastful or assertive.”

The concept of ekila encompasses food taboos, hunting luck, respect for animals, menstrual blood, and proper sharing. Lewis argues that ekila “provides a trail of breadcrumbs for any individual as they grow up, teaching them how to ‘do’ their culture”—with the authority for these rules resting not with any individual but with the forest itself.

This is ideological counter-amplification: a belief system that prevents hierarchy rather than justifying it.

What the Egalitarian Cases Reveal

The existence of genuinely egalitarian societies demonstrates that:

-

Hierarchy is not inevitable: The same species that builds empires also maintains radical equality under different conditions.

-

Egalitarianism requires specific conditions: Dispersed resources, mobility, immediate-return subsistence, and active maintenance mechanisms.

-

Remove the conditions, lose the equality: When the Ju/’hoansi were settled at government posts with boreholes, conflicts increased and hierarchy began emerging. The amplifier (fixed water source) changed the game.

-

The disposition for dominance is universal: Egalitarian societies don’t lack would-be dominators; they suppress them. The effort required for suppression reveals the underlying pressure.

V. The Transition Points: When Amplifiers Emerge

The Neolithic as Amplifier Revolution

The Neolithic transition (the shift from foraging to agriculture) was an amplifier revolution. It introduced:

-

Fixed location: Tied to fields, people could no longer “vote with their feet”

-

Storable surplus: Grain could be accumulated, hoarded, defended

-

Defensible improvements: Irrigation works, cleared fields, built structures represented invested labor that couldn’t be abandoned

-

Population density: More people in smaller areas meant more coordination problems—and more opportunity for coordinators to extract

The archaeological record shows hierarchy emerging rapidly after the Neolithic transition. Çatalhöyük (c. 7500-5700 BCE), one of the earliest large settlements, shows relatively little evidence of social differentiation. But within a few thousand years, Mesopotamian cities display palaces, temples, monumental architecture, and clear evidence of stratification.

This was not because agriculturalists were morally inferior to foragers. It was because agriculture created amplifiers that foraging did not.

The Bronze Age as Weapons Amplifier

The development of bronze metallurgy (c. 3300 BCE in the Near East) introduced weapons asymmetry as an amplifier. Bronze weapons were expensive to produce, requiring tin and copper from distant sources, specialized smiths, and surplus to support non-farming specialists.

This created a class division: those with bronze weapons and those without. A bronze-armed elite could dominate a larger population of stone-tool users. The chariot, developed in the early second millennium BCE, amplified this further—mobile, expensive platforms that required training, maintenance, and breeding programs.

The Code of Hammurabi’s differential punishments by class reflect a society where elites possessed decisive military advantages:

“If a man destroy the eye of another man [of equal status], they shall destroy his eye. If one destroy the eye of a man’s slave, he shall pay one-half his price.”

The slave’s lesser value was not merely ideological; it reflected the slave’s inability to resist or retaliate. Weapons asymmetry made the differential sustainable.

Writing as Informational Amplifier

Writing emerged in Mesopotamia around 3200 BCE, initially for accounting purposes: recording surplus grain, labor obligations, debts. This seemingly neutral technology became a profound amplifier.

Writing enabled:

-

Administration at scale: Coordinating labor, taxes, and distribution across distances beyond personal knowledge

-

Legal codification: Rules that persisted beyond individual memory and could be selectively enforced

-

Knowledge monopoly: Literacy required years of training, concentrating informational power in scribal classes allied with temples and palaces

-

Historical legitimation: Recorded genealogies and divine mandates that justified current arrangements

The illiterate majority could not verify what the texts said. Scribes and priests could claim textual authority for whatever served elite interests. The information asymmetry was itself a source of power.

VI. The Self-Reinforcing Trap

Why Hierarchy Persists Once Established

The amplifier model explains not only hierarchy’s emergence but its persistence. Once established, amplified power creates conditions for its own continuation:

-

Resource extraction: Elites extract surplus from subordinates

-

Reinvestment in amplifiers: Surplus funds weapons, walls, scribes, priests

-

Increased power differential: Elites become more capable of extraction and defense

-

Suppression of alternatives: Resistance is punished; exit is prevented

-

Ideological naturalization: Succeeding generations are taught that hierarchy is natural

-

Repeat: Each cycle widens the gap

This is why revolutions so often fail to produce lasting equality. The revolutionaries may overthrow specific rulers, but if the underlying amplifiers remain (the defensible territory, the stored grain, the weapons monopoly, the administrative apparatus) new hierarchies emerge.

The French Revolution eliminated the monarchy but retained the agricultural surplus, the administrative state, and the information asymmetries of literacy. Napoleon emerged within fifteen years. The Russian Revolution eliminated the Tsar but retained the industrial infrastructure, the security apparatus, and the organizational technology of the vanguard party. Stalin emerged within a decade.

The amplifiers persist and hierarchy regenerates.

The Ratchet Effect

Certain amplifiers, once developed, cannot be abandoned without catastrophic cost. Irrigation-dependent agriculture is the paradigmatic case.

The Mesopotamian city-states depended on irrigation infrastructure that required coordinated labor to maintain. Abandoning the hierarchy that organized this labor would mean:

-

Irrigation canals silting up

-

Agricultural productivity collapsing

-

Population starvation

-

Social collapse

The population was trapped. They could not return to foraging. The land couldn’t support foraging populations at the density agriculture had enabled. They could not abandon irrigation. They would starve. They were locked into a system that required hierarchy to function.

This is the ratchet: each amplifier development creates dependencies that make reversal increasingly costly. Grain storage enables population growth; population growth requires grain storage; grain storage requires defense; defense requires hierarchy; hierarchy becomes inescapable.

VII. Implications

For Understanding History

The amplifier model reframes human history. The question is not “why are humans hierarchical?” (we are not uniformly so) or “why are some cultures more hierarchical?” (culture is downstream of conditions). The question is: what amplifiers existed and who controlled them?

This lens clarifies puzzling patterns:

-

Why empires form along rivers: Rivers concentrate population, enable transportation, and create irrigation opportunities—multiple amplifiers in combination.

-

Why nomads are hard to conquer: They lack fixed amplifiers. There is nothing to seize that would give conquerors leverage.

-

Why mountain peoples often remain autonomous: Terrain prevents agricultural intensification and provides defensive advantages against lowland states.

-

Why ideology matters so much: It is the amplifier that operates even when material amplifiers are evenly distributed.

For Understanding Institutions

Modern democratic institutions can be understood as attempted counter-amplifiers. Mechanisms designed to prevent the conversion of any resource into durable, self-reinforcing power:

-

Separation of powers: Prevents any single actor from controlling all amplifiers

-

Term limits: Prevents the temporal accumulation of political power

-

Antitrust law: Prevents economic amplifier concentration

-

Progressive taxation: Reduces the rate at which wealth amplifies into more wealth

-

Free press: Prevents informational monopoly

-

Universal suffrage: Distributes political amplification broadly

These institutions represent hard-won, historically rare achievements. They are constantly eroded by those who accumulate amplifiers and use them to weaken counter-mechanisms. The amplifier theory predicts that without active maintenance, democracies will drift toward oligarchy, which is precisely what we observe.

For Understanding Ourselves

The amplifier model suggests that humans are neither naturally egalitarian nor naturally despotic. We are conditionally both. Our societies reflect not our nature but our situation—specifically, the amplifiers available and who controls them.

This is simultaneously hopeful and sobering:

Hopeful: Hierarchy is not destiny. Under the right conditions, humans maintain equality. Those conditions can, in principle, be designed.

Sobering: The “right conditions” are extraordinarily difficult to maintain in complex societies. The amplifiers that enable civilization—stored food, specialized knowledge, administrative coordination—are the same amplifiers that enable domination.

The Ju/’hoansi solution (eliminate amplifiers) is unavailable to societies dependent on agriculture, industry, and information technology. We cannot return to the Kalahari.

The alternative is to design counter-amplifiers robust enough to prevent power concentration—while still enabling the coordination that complex societies require. This is the central political problem of human civilization. It has never been permanently solved. The historical record offers no examples of large, complex societies maintaining egalitarianism for more than a few generations.

But the historical record also shows that the problem is understood. Every revolution, every constitution, every declaration of rights represents an attempt to solve it. The attempts have been impermanent, but they have not been futile. Slavery was abolished. Suffrage was expanded. Legal equality was established.

These achievements were not inevitable. They were won against the pressure of accumulated amplifiers. They can be lost if that pressure is not continuously resisted.

VIII. Conclusion: The Permanent Tension

Human beings seek power over others. This is not a moral failing; it is an evolved disposition shared with our primate relatives. But human beings also resist domination by others. An equally evolved disposition that enabled our ancestors to maintain egalitarian societies for most of our species’ existence.

The balance between these dispositions is determined by amplifiers: environmental, technological, social, and ideological factors that extend individual power beyond what collective resistance can counter. Where amplifiers are absent or weak, equality prevails. Where amplifiers concentrate, hierarchy emerges.

History is the record of amplifier accumulation and the social formations it produced. The rise of agriculture created geographic and technological amplifiers. The development of states added social and ideological amplifiers. Each innovation that enabled human flourishing also enabled human domination.

There is no exit from this tension. We cannot renounce the amplifiers and return to foraging; we are eight billion people dependent on systems that require coordination. We cannot embrace the amplifiers and accept domination; our resistance to subjugation is as deep as our drive to subjugate.

What remains is the permanent work of counter-amplification: designing institutions that prevent power concentration while enabling collective action, maintaining those institutions against the constant pressure of would-be dominators, and rebuilding them when they fail.

The Ju/’hoansi mock successful hunters to keep them humble. In complex societies, we need institutions that serve the same function—mechanisms that “cool the hearts” of those who would become chiefs, and “make them gentle.”

This is not a problem to be solved. It is a condition to be managed. The work is never done. But understanding the dynamics—understanding that the problem is neither inevitable destiny nor eliminable disease, but rather a permanent tension arising from our dual nature and the amplifiers we have created—is the first step toward managing it wisely.

Bibliography

Anthropological Sources

Boehm, Christopher. Hierarchy in the Forest: The Evolution of Egalitarian Behavior. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Graeber, David, and David Wengrow. “Many Seasons Ago: Slavery and Its Rejection among Foragers on the Pacific Coast of North America.” American Anthropologist 120, no. 2 (2018): 237-249.

Kelly, Robert L. The Lifeways of Hunter-Gatherers: The Foraging Spectrum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Lee, Richard B. The Dobe Ju/’hoansi. 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2013.

Lewis, Jerome. “Ekila: Blood, Bodies, and Egalitarian Societies.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (2008): 297-315.

Sahlins, Marshall. Stone Age Economics. Chicago: Aldine, 1972.

Smith, Eric A., and Brian F. Codding. “Ecological Variation and Institutionalized Inequality in Hunter-Gatherer Societies.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, no. 13 (2021): e2016134118.

Wiessner, Polly. “Norm Enforcement among the Ju/’hoansi Bushmen: A Case of Strong Reciprocity?” Human Nature 16 (2005): 115-145.

Woodburn, James. “Egalitarian Societies.” Man 17, no. 3 (1982): 431-451.

Historical Sources

Code of Hammurabi. c. 1754 BCE. Translation by L.W. King.

Manusmriti (Laws of Manu). c. 200 BCE – 200 CE. Translations by Georg Bühler, Ganganath Jha, and Patrick Olivelle.

The Book of Lord Shang. 4th-3rd century BCE. Translations by J.J.L. Duyvendak and Yuri Pines.

Secondary Historical Literature

Ames, Kenneth M. “Slaves, Chiefs and Labour on the Northern Northwest Coast.” World Archaeology 33, no. 1 (2001): 1-17.

Donald, Leland. Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Mann, Michael. The Sources of Social Power, Volume 1: A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Scott, James C. Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017.

Scott, James C. The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.