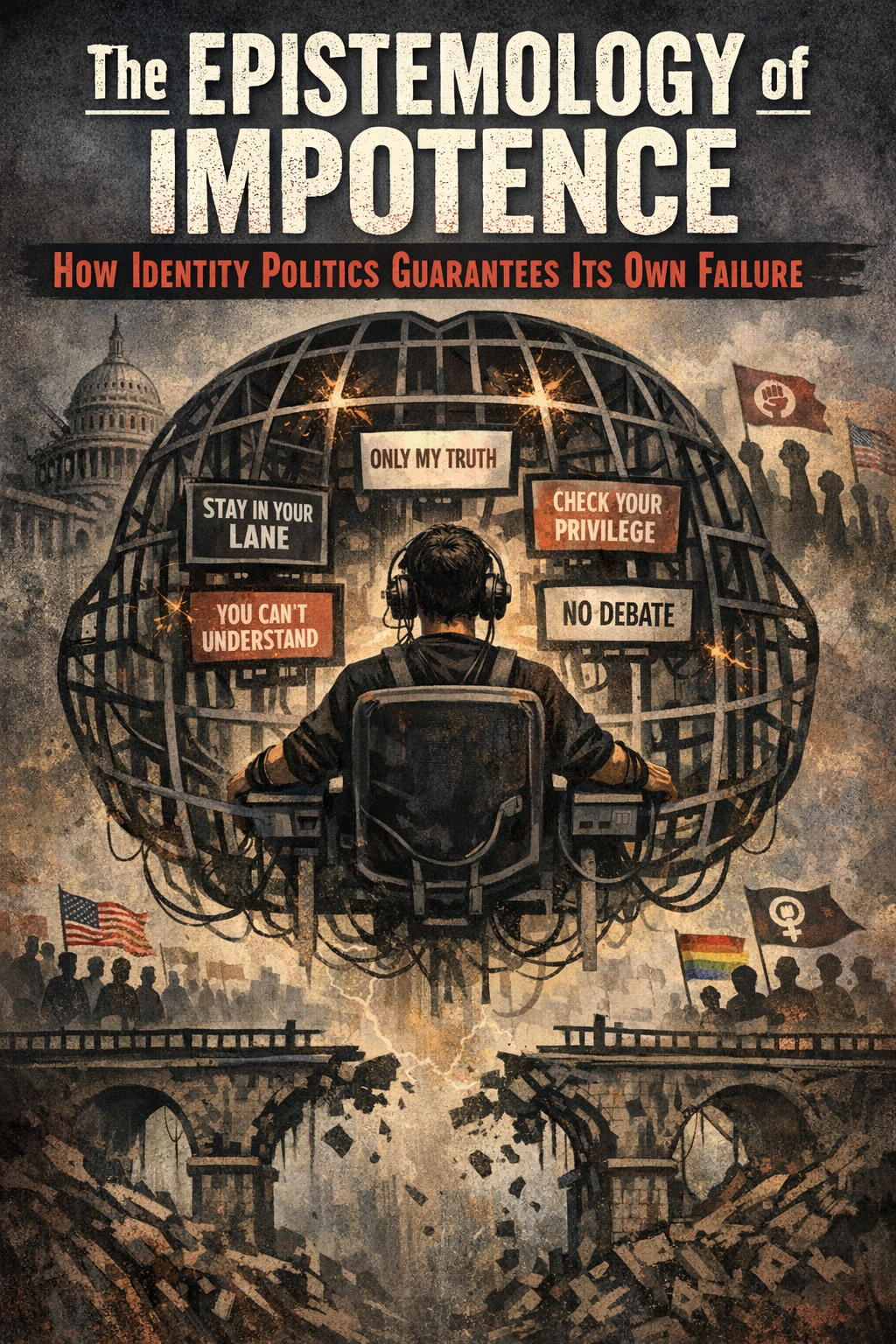

The Epistemology of Impotence: How Identity Politics Guarantees Its Own Failure

Published 2026-01-09

I. The Paradox

The contemporary American left presents a curious puzzle: culturally omnipresent yet politically feeble. It dominates universities, media, corporate HR departments, and the language of public discourse—yet it cannot win elections, build durable coalitions, or construct new institutions. In December 2025, congressional Democrats hit an 18% approval rating, the lowest ever recorded by Quinnipiac University polling. Even among self-identified Democrats, approval of their own party’s congressional delegation was underwater: 42% approve, 48% disapprove.

This is not a failure of messaging or tactics. It is the logical consequence of an epistemology—a theory of knowledge—that makes political success structurally impossible.

II. The Philosophical Foundation

The intellectual architecture of contemporary identity politics rests on what feminist theorists call standpoint epistemology. The theory emerged from academic feminism in the 1970s and 1980s, primarily through the work of Sandra Harding, Patricia Hill Collins, Nancy Hartsock, and Donna Haraway.

The core claims, as articulated by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“Feminist standpoint theorists make three principal claims: (1) Knowledge is socially situated. (2) Marginalized groups are socially situated in ways that make it more possible for them to be aware of things and ask questions than it is for the non-marginalized. (3) Research, particularly that focused on power relations, should begin with the lives of the marginalized.”

Harding’s concept of “strong objectivity” holds that starting inquiry “from the lives of women and, more generally, the lives of marginalized groups” produces better knowledge—not merely different knowledge, but epistemically superior accounts of reality. As Haraway put it: “Feminist objectivity means quite simply situated knowledges.”

This is not merely a claim about bias or perspective. It is a claim about the fundamental structure of knowledge: that who you are determines what you can know, and that some identities have privileged access to truth that others structurally cannot possess.

III. The Self-Refutation

This epistemology contains a fatal internal contradiction.

If all knowledge is situated—bound to the social position of the knower—then the claim “all knowledge is situated” is itself situated. It emerges from a particular academic context (late 20th-century Western feminism), a particular class position (educated professionals), and particular identity categories. By its own logic, it cannot claim universal validity. It is merely one perspective among many, with no greater claim to truth than the perspectives it seeks to critique.

The theory’s proponents attempt to escape this through the “epistemic advantage” thesis: marginalized standpoints see more clearly because oppression forces awareness of social structures that privilege renders invisible. But this move simply relocates the contradiction. Either:

-

There is a standpoint-independent truth (that oppression provides epistemic clarity) accessible to anyone who reasons correctly—which abandons the situated knowledge thesis entirely, or

-

The claim that marginalized standpoints are epistemically privileged is itself merely the situated claim of those standpoints—in which case it has no authority over anyone not already within that standpoint.

You cannot simultaneously hold that all knowledge is identity-bound and that your identity-bound knowledge should compel universal assent.

IV. The Political Consequences

This is not merely a philosopher’s quibble. The epistemology produces specific, predictable political dysfunctions:

A. The Impossibility of Persuasion

If knowledge is fundamentally shaped by social position, then persuasion across identity lines becomes incoherent in principle. You cannot argue someone into understanding—they either occupy a standpoint that grants them access to the relevant knowledge, or they don’t. As one critic summarized the position: “Standpoint theorists argue that standpoints are relative and cannot be evaluated by any absolute criteria.”

Political coalitions require persuasion. They require convincing people who do not already agree with you that your account of reality is accurate and your proposed solutions are sound. But if disagreement is reframed as a structural feature of divergent social positions rather than a gap that argument can bridge, coalition-building becomes impossible.

The result is a politics of demand rather than persuasion—a politics that can only address those already converted or those with institutional power to coerce.

B. The Elimination of Shared Ground

Democratic politics presupposes a shared arena where citizens can contest claims on common terms. Standpoint epistemology eliminates this arena by definition. If your social position determines what you can know, and my social position determines what I can know, there is no neutral ground on which we might adjudicate our disagreement.

Political scientist Adolph Reed Jr., a Black leftist critic of identity politics, identifies this dynamic precisely:

“Through a process of semantic inflation and infiltration, over the last four decades, what people generally understand to be the left has been once again disconnected from political economy and linked to performances of identity.”

When politics becomes a matter of identity performance rather than contestable claims about shared reality, the very possibility of democratic deliberation dissolves.

C. The Sole Recourse to Power

If persuasion is impossible and shared ground is eliminated, what remains? Only power. The logic of standpoint epistemology leads inexorably to a conception of politics as zero-sum struggle between identity groups, where the only relevant question is which group controls institutions.

This explains the contemporary left’s simultaneous cultural dominance and political impotence. It has optimized for institutional capture—HR departments, university administrations, media organizations—rather than electoral success. These are the levers that can be pulled without persuading anyone. You don’t need to win an argument if you control the terms of employment.

But institutions captured through this method are brittle. They require continuous policing of discourse rather than genuine buy-in. And they cannot deliver the electoral majorities required to implement policy at scale.

V. The Evidence

The Great Awokening

Researcher Zach Goldberg documented what he termed “The Great Awokening”—a dramatic leftward shift on racial and identity issues among white liberals beginning around 2012-2014. His data shows:

“In the past five years, white liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter.”

This shift was concentrated in the educated professional class and amplified through social media. It did not reflect a broader coalitional expansion—if anything, it alienated working-class voters of all races while making white liberals more “progressive” than the minorities they claimed to champion.

Electoral Results

The political fruits of this shift:

-

2016: Trump wins the presidency, Republicans control House and Senate

-

2024: Trump wins again, with improved margins among Black and Hispanic voters

-

2025: Democratic congressional approval at historic lows

-

State legislatures: Republicans control 56% of state legislative chambers

Mark Lilla, a liberal professor at Columbia, offered a blunt diagnosis in The Once and Future Liberal:

“American liberalism fell under the spell of identity politics, with disastrous consequences. Driven originally by a sincere desire to protect the most vulnerable Americans, the left has now unwittingly balkanized the electorate, encouraged self-absorption rather than solidarity, and invested its energies in social movements rather than in party politics.”

The Construction Gap

The movements and institutions that materially improved Americans’ lives in the 20th century—the labor movement, Social Security, Medicare, the Civil Rights Act—were built through persuasion, coalition, and the unglamorous work of winning elections and passing legislation.

The contemporary identity-focused left builds nothing comparable. It can get people fired. It can mandate training sessions. It can shift the language of corporate communications. What it cannot do is construct institutions that generate broad prosperity or win the sustained electoral majorities required to protect vulnerable populations through law.

As Reed and co-author Walter Benn Michaels put it:

“Racism is real and anti-racism is both admirable and necessary, but extant racism isn’t what principally produces our inequality and anti-racism won’t eliminate it.”

A politics of symbolic representation and discourse management cannot address structural economic conditions. It can only offer representation within existing hierarchies, not transformation of them.

VI. The Trap

The epistemology creates a trap from which escape is nearly impossible.

If you are inside the framework, criticism registers as evidence of the critic’s compromised standpoint. Disagreement becomes diagnostic—proof that the dissenter lacks the social position required to see clearly. This immunizes the framework against correction from within.

If you are outside the framework, your criticism is dismissed a priori as the predictable product of your privileged (or otherwise inadequate) standpoint. This immunizes the framework against correction from without.

The result is an intellectual monoculture that experiences its own stagnation as righteousness. The framework cannot learn because it has defined learning from outside itself as impossible.

VII. The Alternative

The alternative is not to pretend that social position doesn’t shape perspective. It obviously does. People’s experiences differ, and those differences inform what they notice and what they care about. This banal observation requires no exotic epistemology.

The alternative is to maintain that arguments can be evaluated on their merits regardless of who makes them. That evidence is evidence. That logic is logic. That a claim’s truth or falsity is independent of the identity of the claimant.

This is the only basis on which democratic politics can function. It is the only basis on which persuasion is possible. It is the only basis on which coalitions can be built across difference.

A politics grounded in universalist claims—that exploitation is wrong regardless of who is exploited, that justice applies to all, that material conditions matter more than symbolic representation—can expand. It can persuade. It can build.

A politics grounded in identity epistemology can only balkanize, demand, and eventually collapse into irrelevance while congratulating itself on its moral purity.

VIII. Conclusion

The contemporary American left has adopted an epistemology that guarantees its political failure. By making identity the foundation of knowledge claims, it has eliminated the shared ground on which democratic persuasion depends. By treating disagreement as a structural feature of social position rather than a gap argument can bridge, it has abandoned the very possibility of coalition.

The result is cultural influence without political power—the ability to shape language and police discourse while losing elections and failing to improve material conditions for anyone.

This is not an accident. It is the logical consequence of the theory. An epistemology that forecloses persuasion cannot build majorities. A movement that defines outsiders as structurally incapable of understanding cannot expand. A politics that offers identity performance rather than material improvement cannot sustain loyalty.

The philosophical error produces the political outcome. The epistemology guarantees the impotence.

Those who wish to actually change things—to build power, win elections, construct institutions, and improve lives—must begin by rejecting the framework that makes such achievements impossible in principle. The first step toward political effectiveness is epistemic humility: the recognition that your opponents might understand something you don’t, that argument can change minds, and that coalition requires persuasion rather than denunciation.

This is not a counsel of moderation. It is a counsel of seriousness. The question is whether you want to be right or become powerful enough to make things right.

The current left has chosen the former. The results speak for themselves.

“The point of identity politics is not to advance a program but to claim the moral authority to silence others.” — Adolph Reed Jr.

“Democrats need to understand how we lost our grip on the American imagination. Why is it that we are unable to project an image of the kind of country that we want to build together, a vision that would draw people together?” — Mark Lilla

“In the past five years, white liberals have moved so far to the left on questions of race and racism that they are now, on these issues, to the left of even the typical black voter. This change amounts to a ‘Great Awokening.’” — Zach Goldberg