The Theological Structure of Secular Progressivism

Published 2026-01-09

Abstract

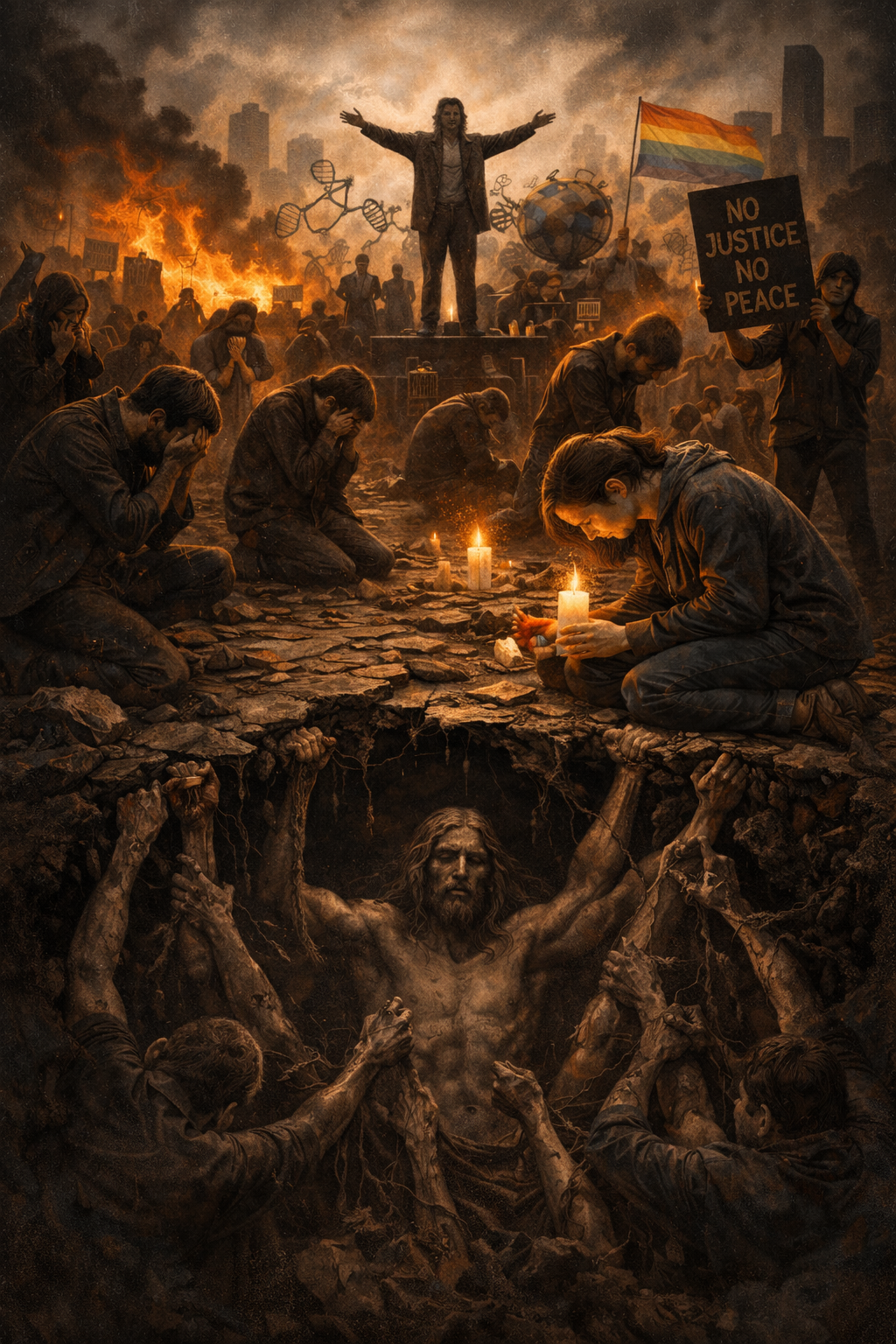

This essay argues that contemporary progressive politics, particularly among white liberals in the United States, operates according to a fundamentally Christian moral psychology that persists despite—and perhaps because of—the abandonment of Christian theology. Drawing on Nietzsche’s critique of slave morality, Girard’s analysis of the scapegoat mechanism, and recent empirical research on racial attitudes, I demonstrate that the valorization of victimhood, the imperative toward self-sacrifice, and the structure of confession and penance that characterize modern progressivism represent not a departure from Christianity but its unconscious continuation. The result is a political theology that retains Christianity’s crucifixion while eliminating its resurrection—producing perpetual guilt without the possibility of grace.

I. The Problem: Christianity Without God

Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous declaration that “God is dead” was not a triumphant announcement of atheism’s victory but a warning about what would follow. In Twilight of the Idols, he observed: “When one gives up the Christian faith, one pulls the right to Christian morality out from under one’s feet. This morality is by no means self-evident... By breaking one main concept out of Christianity, the faith in God, one breaks the whole: nothing necessary remains in one’s hands.”

Yet Nietzsche’s prediction proved only half correct. Western societies did abandon Christian theology, but they did not abandon Christian morality. Instead, as Nietzsche anticipated elsewhere, the moral superstructure persisted even as its metaphysical foundation crumbled. “God is dead,” he wrote in The Gay Science, “but given the way of men, there may still be caves for thousands of years in which his shadow will be shown.”

The historian Tom Holland, in Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World (2019), has recently documented this phenomenon with extraordinary comprehensiveness. Holland argues that concepts modern Westerners consider secular, universal, or simply self-evident—human rights, the equal dignity of persons, special concern for the marginalized, the moral superiority of suffering over power—are in fact distinctively Christian inheritances. “In a West that is often doubtful of religion’s claims,” Holland writes, “so many of its instincts remain—for good and ill—thoroughly Christian.” The very concept of “secularism” itself, the separation of sacred and political, is a notion Western civilization inherited from Christianity and is not self-evident in other cultures.

What Holland documents historically, Nietzsche diagnosed psychologically. In On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), Nietzsche traced the origins of what he called “slave morality”—a moral system that inverts the aristocratic equation of good with strength, nobility, and power, replacing it with an equation of good with weakness, suffering, and humility. This “transvaluation of all values,” Nietzsche argued, was Christianity’s revolutionary contribution to Western civilization. The meek inherit the earth. The last shall be first. Blessed are those who are persecuted.

Nietzsche’s crucial insight was that this moral psychology would survive the death of the God who sanctioned it. Modern atheists, he observed, continue to believe in Christian morality without recognizing it as such. “Interestingly,” writes the philosopher Justin Remhof summarizing Nietzsche, “atheists often fail to understand the true extent of atheism... Atheists continue to embrace traditional moral principles—e.g., that we should respect people or reduce suffering—and these principles imply that all people are morally equal. Nietzsche claims that belief in God is the only way to ensure moral equality. If God were to exist, then we would all be equal as God’s children. But what makes us equal if God is dead? For Nietzsche: nothing.”

This observation has profound implications for understanding contemporary progressive politics. If secular progressivism is, as Holland argues, “deeply Pauline”—if its commitment to the oppressed, its suspicion of power, and its hope for universal justice derive from Christian moral psychology rather than from reason or science—then we should expect to find Christian theological structures operating beneath its secular surface.

We do.

II. The Transvaluation Preserved: Slave Morality in Secular Form

Nietzsche’s account of the “slave revolt in morality” begins with a psychological observation: those who lack power cannot achieve satisfaction through the direct exercise of strength. The weak cannot defeat the strong on the strong’s own terms. What they can do is redefine the terms themselves—declaring that strength is evil, that weakness is virtue, that suffering confers moral authority.

This transvaluation, Nietzsche argued, was not merely a defensive maneuver but a creative act powered by what he called ressentiment—a festering resentment that, unable to discharge itself in direct action, instead “becomes creative and gives birth to values.” Slave morality “from the outset says No to what is ‘outside,’ what is ‘different,’ what is ‘not itself’; and this No is its creative deed.”

The structure Nietzsche identified—the valorization of victimhood, the suspicion of power, the moral authority of suffering—maps precisely onto contemporary progressive politics. Consider the concept of “lived experience” as a source of epistemic and moral authority. Within progressive frameworks, the experience of marginalization confers a special access to truth that those in dominant positions cannot achieve. The oppressed see what the oppressors cannot see. This is not merely an empirical claim about perspective; it is a moral claim about the relative value of different positions in social hierarchies.

Or consider the concept of “privilege.” To be privileged is not merely to have material advantages but to be morally compromised by them. Privilege is original sin—an inherited stain that cannot be removed through individual action but only acknowledged through perpetual confession. The parallel to Christian soteriology is not metaphorical but structural.

John McWhorter, a linguist at Columbia University, has documented these parallels extensively in Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America (2021). McWhorter argues that contemporary antiracism functions not as a political ideology but as a religion, complete with:

-

Original sin: white privilege (inherited guilt you did not choose but must acknowledge)

-

Confession: “doing the work,” acknowledging complicity

-

Catechism: mandatory trainings, reading lists, correct terminology

-

Scripture: canonical texts (DiAngelo, Kendi, Coates)

-

Heresy: denial of the framework (”white fragility,” “tone policing”)

-

Excommunication: cancellation, social exile

“I do not mean that these people’s ideology is ‘like’ a religion,” McWhorter clarifies. “I mean that it actually is a religion. An anthropologist would see no difference in type between Pentecostalism and this new form of antiracism.”

What McWhorter identifies as religion is more precisely identified as Christianity without God—the preservation of Christian moral psychology in secular form. The “Elect,” as McWhorter calls progressive antiracists, are not generic religious believers but specifically Christian in their moral structure, even when they would reject Christianity explicitly.

III. The Empirical Puzzle: White Liberal Out-Group Preference

If contemporary progressivism preserves Christian moral psychology, we should expect to observe something unprecedented: a dominant group that systematically devalues itself relative to subordinate groups. This would be the political expression of slave morality’s transvaluation—not the weak declaring themselves virtuous despite their weakness, but the strong declaring themselves guilty because of their strength.

This is precisely what we observe.

Zach Goldberg, a researcher at Florida State University, has documented what he calls “The Great Awokening”—a dramatic shift in white liberal racial attitudes beginning around 2012-2014. Using data from the American National Election Studies (ANES), Goldberg found something remarkable: “White liberals were the only subgroup exhibiting a pro-outgroup bias—meaning white liberals were more favorable toward nonwhites and are the only group to show this preference for groups other than their own. Indeed, on average, white liberals rated ethnic and racial minority groups 13 points (or half a standard deviation) warmer than whites.”

This finding is extraordinary. As Goldberg notes, “the emergence and growth of a pro-outgroup bias is actually a very recent, and unprecedented, phenomenon.” No other demographic group in the ANES data displays this pattern. Black liberals, Hispanic liberals, Asian liberals—all show standard in-group preference, rating their own groups more warmly than others. Only white liberals invert this universal human tendency.

The phenomenon is not restricted to feeling thermometers. Goldberg’s research shows that white liberals are more likely than any other group—including Black respondents—to say that discrimination is the primary cause of racial disparities. They are more likely to support policies that would disadvantage whites as a group. And, remarkably, 53% of white liberals believe that white people should feel guilty about racial inequality.

From an evolutionary or game-theoretic standpoint, this is bizarre behavior. No group prospers by systematically preferring out-groups to in-groups. Yet from the standpoint of Christian moral psychology, it makes perfect sense. The last shall be first. Blessed are the persecuted. It is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven.

White liberals, on this account, are enacting a secularized Christianity. They occupy the position of the rich man, the Pharisee, the powerful. Their moral framework tells them that this position is spiritually perilous—that power corrupts, that privilege blinds, that the dominant are morally suspect precisely because of their dominance. The appropriate response is not to defend one’s position but to surrender it, to sacrifice one’s own interests for the sake of the marginalized.

This is not hypocrisy. It is theology.

IV. The Sacrificial Logic: Girard and the Persistence of Scapegoating

The French anthropologist René Girard (1923-2015) developed a theory of culture that illuminates why progressive Christianity-without-God produces not peace but perpetual conflict. Girard’s mimetic theory begins with a simple observation: human desire is imitative. We want what others want. This leads inevitably to rivalry and conflict.

Girard argued that human societies solve this problem through the scapegoat mechanism. When mimetic rivalry threatens to tear a community apart, the community achieves unity by redirecting its violence onto a single victim—a scapegoat whose sacrifice restores peace. “All are one,” Girard observed, “against and by virtue of, the rejected, demonized, scapegoated, adversarial Other.”

The crucial role of Christianity in Girard’s account is that it reveals this mechanism. The crucifixion of Jesus exposes scapegoating for what it is—the murder of an innocent victim by a mob that believes itself righteous. “The Bible,” Girard wrote, “marks a decisive break with the otherwise universal phenomenon of prohibition, scapegoating, and sacrificial repetition... The crucifixion reveals that the victim of collective lynching is always innocent and that sacrificial killings are unjustified.”

Christianity, in Girard’s view, was supposed to end scapegoating by making it visible. Once you see the mechanism, it should lose its power. You can no longer believe in the victim’s guilt, so killing the victim no longer unifies the community.

But what happens when you preserve Christianity’s moral psychology while abandoning its theology? You get the worst of both worlds: a culture that valorizes victims without the revelation that ends scapegoating. The scapegoat mechanism continues to operate, but now it rotates endlessly, finding new victims to sacrifice, new demons to exorcise, new sins to confess.

This explains why progressive politics seems structurally incapable of completion. There is no final victory, no achieved justice, no point at which the work is done. New sins are always discovered. New victims always emerge. New confessions are always demanded. The framework requires ongoing sin to maintain its moral structure—without oppressors to confess and victims to be elevated, the entire apparatus loses its purpose.

Richard Cocks, a philosopher at SUNY Oswego, observes: “It is possible that the rise we see in scapegoating in online culture and late night ‘comedy’ is partly due to anonymity and partly due to the decline of Christianity as a cultural force.” The mechanism persists; the revelation that was supposed to end it has been forgotten.

V. Crucifixion Without Resurrection

The deepest problem with secular Christianity is not that it preserves Christian morality but that it preserves only half of it. Christianity is not merely a religion of crucifixion—it is a religion of crucifixion and resurrection. The cross is not the end of the story but its turning point. Death gives way to life. Sin gives way to grace. The guilty are forgiven.

Secular progressivism retains the cross while eliminating Easter.

Consider the structure of confession in traditional Christianity. The believer acknowledges sin, expresses genuine contrition, receives absolution, and is restored to the community of the faithful. The process is painful but finite. There is an end to guilt. Grace is available.

Now consider the structure of confession in secular progressivism. The privileged acknowledge their privilege, express their commitment to “doing the work,” and... then what? There is no absolution. The work is never done. As Robin DiAngelo writes, racism is “like the air we breathe”—permanent, inescapable, requiring perpetual vigilance. The confession must be repeated endlessly, but it never achieves its purpose. There is crucifixion without resurrection, guilt without grace, penance without absolution.

This produces a distinctive psychological profile: anxiety without peace, confession without forgiveness, sacrifice without redemption. The traditional Christian could hope for heaven. The secular progressive can only hope to be slightly less complicit in systems of oppression that will never be dismantled.

McWhorter observes this dynamic operating in contemporary antiracist education: “The idea is to help people who need help. The modern idea that microaggressions and how white people feel in their heart of hearts is what we should be thinking about to me is a detour.” The detour is precisely the replacement of action with confession, of material change with psychological transformation, of resurrection with perpetual crucifixion.

The affect of secular progressivism is telling. It does not produce the joy traditionally associated with religious faith—the “good news” of the Gospel. It produces guilt, anxiety, and exhaustion. This is not surprising if progressivism is Christianity without its culmination. A religion of crucifixion alone would necessarily be a religion of suffering without hope.

VI. The Political Calculus: Self-Sacrifice as Moral Strategy

We can now return to the puzzle that motivated this essay: why would white liberals adopt a political framework that systematically devalues their own group?

The answer is that they are making a moral choice, not a political one—and the moral framework within which they operate has deep Christian roots.

Consider the basic political situation. Any political coalition divides the population into those who benefit and those who pay the costs. In democratic politics, every victory is someone else’s defeat. This is the inescapable logic of collective action.

A person choosing which coalition to join might reasonably ask: which side should I be on? From a purely self-interested standpoint, the answer is obvious—join the coalition that benefits you. But Christian moral psychology rejects this calculus. Self-interest is sin. The first shall be last. Blessed are the persecuted.

On this moral framework, it is better to be the victim than the victimizer, better to suffer than to cause suffering, better to sacrifice than to take. If one must choose between a coalition that elevates one’s own group and a coalition that elevates others at one’s own expense, the Christian choice is clear: choose the cross.

This explains why the phenomenon is concentrated among white liberals rather than liberals generally. Black liberals, Hispanic liberals, and Asian liberals can support progressive politics while simultaneously benefiting from it (or at least not being explicitly targeted by it). Only white liberals face the choice in its pure form: a political framework that explicitly names their group as the problem and demands their subordination as the solution.

Their embrace of this framework is not weakness or self-deception. It is Christianity.

Or rather, it is Christianity without its redemptive dimension—sacrifice without resurrection, guilt without grace, the cross without Easter. It is the moral genius of Christianity perverted into a structure of perpetual penance, where the privileged must forever confess sins that can never be forgiven, bear guilt that can never be absolved, and make sacrifices that can never be enough.

VII. Nietzsche’s Warning Revisited

Nietzsche understood that the death of God would not immediately produce a new morality. The old morality would persist, but in increasingly pathological forms. Without God to guarantee meaning, without resurrection to redeem suffering, without grace to complete repentance, Christian morality would become a machinery of endless guilt.

“The madman,” Nietzsche wrote in The Gay Science, came to the marketplace announcing God’s death, but the people did not understand. “This deed is still more remote to them than the remotest stars—and yet they have done it themselves!”

We are the people in the marketplace. We have killed God but continue to live by His morality. We have abandoned the theology but preserved the psychology. We experience guilt without the possibility of absolution, penance without the hope of grace, crucifixion without resurrection.

The political consequences are profound. A moral framework that valorizes victimhood produces a politics of competitive suffering. A moral framework that requires perpetual confession produces a culture of surveillance and denunciation. A moral framework that offers no forgiveness produces permanent division between the saved and the damned.

This is not to say that Christian moral insights are worthless. The conviction that every person has equal dignity, that the powerful should serve the weak, that suffering matters morally—these are genuine moral achievements, and Holland is right that they derive from Christianity. But these insights were embedded within a larger theological framework that gave them meaning and limit. Extracted from that framework, they become pathological.

Tom Holland asks the essential question: “If secular humanism derives not from reason or from science, but from the distinctive course of Christianity’s evolution—a course that, in the opinion of growing numbers in Europe and America, has left God dead—then how are its values anything more than the shadow of a corpse? What are the foundations of its morality, if not a myth?”

He leaves the question hanging. So must we.

VIII. Conclusion: The Fork in the Road

We stand at what Holland identifies as a fork in the road. One path continues the secularization of Christian morality—the progressive project of achieving Christian ends through non-Christian means, valorizing victims without revealing the scapegoat mechanism, demanding sacrifice without offering redemption.

A second path, which Nietzsche advocated, would abandon Christian morality altogether—returning to what he called “master morality,” the aristocratic valuation of strength, power, and self-assertion. This is the path of genuine post-Christianity, but few who think they want it could stomach its implications. As Holland notes, even the Nazis, who explicitly rejected Christianity, could not fully escape its moral categories.

A third path would be the revival of Christianity itself—the recovery of resurrection alongside crucifixion, grace alongside guilt, absolution alongside confession. This would preserve the moral achievements of the Christian revolution while restoring their theological foundation.

What is not available is the path we are currently on: Christianity without Christ, crucifixion without resurrection, perpetual guilt without the possibility of grace. This is not a stable resting point but a transitional phase—a shadow cast by a corpse, as Holland puts it, which must eventually either be revived or allowed to fade.

The white liberal who prefers the coalition that demeans his own group is not irrational within his moral framework. He is following the logic of Christian sacrifice to its conclusion. His mistake is not moral but theological: he has embraced the cross without understanding that the cross was supposed to be empty.

References

Girard, René. Violence and the Sacred. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

Girard, René. Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1987.

Goldberg, Zach. “America’s White Saviors.” Tablet Magazine, June 5, 2019.

Holland, Tom. Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World. New York: Basic Books, 2019.

McWhorter, John. Woke Racism: How a New Religion Has Betrayed Black America. New York: Portfolio, 2021.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. On the Genealogy of Morals. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books, 1989 [1887].

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage Books, 1974 [1882].

Nietzsche, Friedrich. Twilight of the Idols. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. London: Penguin Books, 1990 [1889].