The Exhaustion That Cannot Rest

Published 2026-01-11

This is the riddle I place before you: a weariness that forbids rest. A depletion that demands more. A sickness that has made recovery itself into a symptom of the disease.

I.

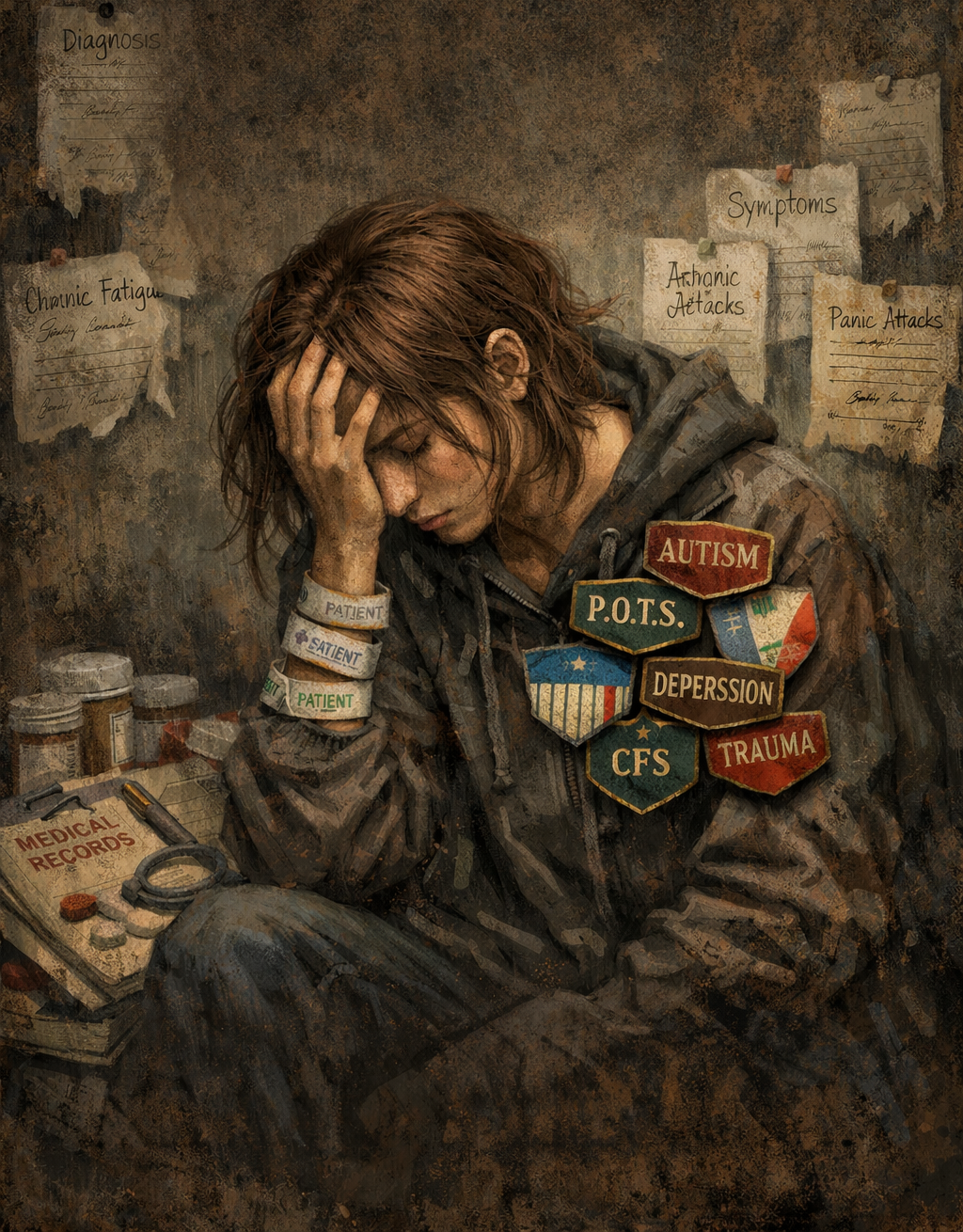

They are tired—have you not noticed? Look at them: their bios a litany of diagnoses, their disorders worn like medals from a war against themselves. ADHD. Autism. POTS. Anxiety. Depression. Chronic fatigue. Each label a credential, each syndrome a badge of belonging. They have medicalized their souls and found, in the clinical vocabulary, an identity that cannot be questioned—for who would doubt a diagnosis? Who would argue with a condition? They are not people who happen to suffer; they are their suffering. The wound has become the self. And so they curate their symptoms like others curate achievements, announcing themselves not by what they have done but by what has been done to them, what has gone wrong in them, what they endure. This is their introduction: not "I am" but "I have." Not a name but a patient history.

They are exhausted. And yet they cannot stop.

This is the riddle I place before you: a weariness that forbids rest. A depletion that demands more. A sickness that has made recovery itself into a symptom of the disease.

How did this come to pass? By what genealogy did we arrive at a soul that is simultaneously burnt out and driven?

I will tell you. Three poisons have entered the modern spirit. Separately, each would sicken. Together, they have constructed a cage—invisible, interior, inescapable. The bars are made of ideas. The lock is made of guilt. And the prisoner has been convinced that the cage is a temple.

II. The First Poison: The Cult of the Wound

There has arisen in our time a new reverence: the veneration of suffering.

Not the overcoming of suffering—that was the old nobility, the tragic sense, the amor fati that said yes to life including its pain. No, this new cult worships the wound as wound. It makes an identity of injury. It builds a throne from victimhood and calls the sitter sacred.

Observe the mechanics: To have suffered is to possess authority. The traumatized one speaks, and others must listen—not because their argument compels, but because their pain consecrates. To question them is to “invalidate.” To disagree is to “retraumatize.” To demand evidence is to harm.

Thus has “lived experience” become an epistemic trump card, played to end all discussion. The wound speaks; reason genuflects.

But here is the trap within the trap: the authority exists only so long as the wound remains open. To heal is to lose standing. To recover is to surrender the throne. The traumatized one is invested in their trauma—it is their credential, their identity, their claim upon the world’s attention.

And so the wound must be tended. Narrated endlessly. Processed in perpetuity. The scab must be picked each morning lest it threaten to close. A whole industry arises—therapists, workshops, memoirs, support groups—all dedicated to ensuring that the wound never heals, that the sufferer never stops suffering, that the identity remains intact.

They call this “healing.” But healing that never ends is not healing. It is maintenance of the disease.

III. The Second Poison: The Inheritance of Guilt

Beside the cult of the wound, another doctrine has taken root: the doctrine of collective guilt.

Not guilt for what one has done—that would be intelligible, the ordinary guilt that follows transgression and may be expiated through confession, restitution, amendment. No, this is guilt for what one is. Guilt by birth. Guilt by ancestry. Guilt written on the skin, inherited in the blood, carried in the name.

The white inherits the guilt of slavery, of colonialism, of every crime committed by anyone who shared their complexion across five centuries. The male inherits the guilt of patriarchy, of every abuse by any man, of the mere fact of occupying space in a world that was built—they are told—for his benefit.

This guilt cannot be discharged. There is no restitution sufficient. There is no confession final. The guilty one may acknowledge their guilt—indeed, they must, constantly, or be accused of “denial” and “fragility.” But acknowledgment does not absolve. It merely demonstrates that one understands one’s guilt, which is the prerequisite for the only activity permitted: the work.

“Doing the work.” The phrase recurs like a catechism. Reading the books. Attending the trainings. Examining one’s privilege. Interrogating one’s biases. Confessing. Confessing again. There is always more work. The work never ends because the guilt is ontological—woven into being itself, not action.

And here is the genius: the guilty cannot contest. To argue against the framework is to display “fragility”—which proves the guilt. To remain silent is “complicity”—which proves the guilt. To speak is to “center oneself”—which proves the guilt. Every move within the game confirms the game’s premises. There is no move that constitutes legitimate disagreement, because disagreement itself has been defined as symptom.

The one who claims innocence is most guilty. The one who protests is most fragile. The one who questions is most in need of education.

Epistemic checkmate. The game is over before the first piece moves.

IV. The Third Poison: The Entrepreneur of the Self

These first two poisons might merely paralyze. A traumatized populace, a guilty populace—these could become inert, passive, waiting. But our age has added a third element that makes the mixture volatile.

The old tyrannies were external. The overseer watched; the worker obeyed; the whip fell on the disobedient. But the soul remained untouched. One could hate the master while bending to his will. One could preserve, in the secret interior, a self that refused.

The new tyranny has no overseer. No external compulsion. No whip. There is only you—measuring yourself against an infinite demand for optimization. The factory has moved inside. You are both manager and managed, entrepreneur and enterprise, the one who demands and the one who must deliver.

This is the “achievement subject.” Not the disciplined subject of old, who obeyed or rebelled. The achievement subject believes they are free. No one is forcing them. They choose to optimize, improve, develop, grow. They want to become their best self.

But this freedom is the most perfect unfreedom. The external master could be overthrown. The internal master is you—how do you overthrow yourself? The overseer could be escaped. But you cannot escape your own interiority. The cage has no location because you are the cage.

And this achievement subject needs projects. Metrics. Progress. The entrepreneur cannot sit still; the enterprise must grow or die. Every domain of life becomes a site of optimization. Fitness. Diet. Relationships. Productivity. Sleep itself is optimized—tracked, measured, improved—turned into one more input for the great project of self-manufacture.

The question “Who am I?” has been replaced by “What am I becoming?” And the answer is: never enough. The horizon recedes as you approach. The goalpost moves as you near it. You are not optimizing toward completion; you are optimizing as such, optimization without terminus, growth without destination.

Burnout is the inevitable result. But burnout cannot be rested away, because rest would mean stopping the project. And stopping is failure. Stopping is death. So the burnt-out achievement subject seeks... recovery techniques. Optimization of rest. Productivity hacks for the exhausted. The project of recovering from the project.

V. The Synthesis: A Perfect Prison

Now observe how these three poisons combine.

Each alone might be escaped. The trauma cult could be rejected by those who refuse to identify with their wounds. The guilt doctrine could be contested by those who insist on innocence. The achievement drive could be abandoned by those who accept “enough.”

But together they form a closed system. Each blocks the exit that the others leave open. Each solves a problem the others create. The result is a cage with no door, a room with no windows, a prison whose walls are made of the prisoner’s own beliefs.

The wound gives the project its object. What does the achievement subject work on? Themselves. But which self? The traumatized self. The self that needs healing, processing, recovery. Trauma becomes the content of the project. The infinite wound meets the infinite optimization drive, and they merge: the project of healing that never heals.

The guilt gives the project its fuel. Why can’t the achievement subject rest? Because rest is privilege. Only those unburdened by guilt may rest. Only the innocent may sleep peacefully. The guilty must work—and now there is always work to do. Examining privilege. Interrogating bias. Reading the books. Doing the work. The infinite guilt meets the infinite drive, and they merge: the project of expiation that never expiates.

The achievement drive gives trauma and guilt their mode. Without it, the wounded might simply suffer. The guilty might simply feel bad. But the achievement subject cannot merely suffer or feel—they must do something about it. Transform it into project. Make it productive. Track progress. Set goals. The wound and the guilt become opportunities for growth.

Do you see the perfection? The traumatized cannot heal—but they can work on healing. The guilty cannot be absolved—but they can do the work. The achiever cannot stop—but trauma and guilt give them infinite material.

Each poison is the antidote to the others’ side effects, while amplifying their primary toxicity.

VI. The Contagion: How the Cage Spreads

“But I am not traumatized,” says one. “I feel no guilt,” says another. “I do not optimize myself,” says a third.

And perhaps they believe this. Perhaps they have not yet consciously adopted the doctrines. Perhaps, in their private hearts, they even resist.

It does not matter.

Here is what the philosophers of desire have taught us: we do not know what we want. We learn to want by watching others want. Desire is not born in the individual soul; it is copied. It spreads through imitation, through modeling, through the contagion of the group.

The child does not want the toy until another child reaches for it. The adult does not want the career, the partner, the lifestyle, until they see it wanted by those they admire, those they compete with, those they wish to resemble. We are mimetic creatures. We borrow our desires from one another like flames passed from candle to candle.

And so the three poisons spread—not through argument, not through conscious adoption, but through imitation.

Watch: The young person enters the university, the workplace, the social circle. They observe what is valued. They note who speaks with authority, who is deferred to, who is praised, who is shunned. They see that the wounded are honored. They see that the guilt-bearing are virtuous. They see that the self-optimizing are admired.

They do not decide to adopt these values. They absorb them. They begin to speak the language—not from conviction, but from belonging. They learn to identify micro-traumas in their past, to ## examine their privilege, to frame their lives as projects of growth. Not because they believe, but because this is what one does. This is how one signals membership. This is how one avoids exile.

And here is the trap: behavior precedes belief. The gestures come first; the conviction follows. One performs the guilt before one feels it. One narrates the trauma before one owns it. One optimizes before one is driven.

But the performance becomes real. The mask grows into the face. The imitated desire becomes indistinguishable from authentic desire—indeed, was there ever a difference? The young person who began by mimicking ends by believing. The cage that was first external—the social pressure to conform—has become internal. The bars have been swallowed.

This is why conscious rejection is not enough. You may intellectually refuse all three poisons. But you live among the poisoned. You breathe the same air. You compete for the same status. You desire according to the same models.

The one who loudly rejects trauma culture still watches for their own micro-wounds, still monitors their emotional states, still speaks of “boundaries” and “triggers.” The one who denies collective guilt still feels the pull to apologize, to caveat, to demonstrate awareness. The one who mocks self-optimization still tracks, measures, improves—if not the self, then the portfolio, the follower count, the physique.

The ideology does not require your assent. It only requires your imitation. And you are already imitating.

This is how a cage can capture those who do not believe in cages. This is how a religion spreads among those who consider themselves atheists. The mimetic mechanism bypasses the conscious mind entirely. By the time you notice you are in the cage, the bars have long since become invisible—because they are now inside.

VII. The Colonization of the Interior

What remains unoccupied?

Feeling has been captured by trauma. Every emotion is now interpreted through the lens of wound and trigger. Sadness is not sadness; it is unprocessed grief. Anger is not anger; it is trauma response. Joy itself becomes suspect—is it authentic, or is it dissociation? Avoidance? Spiritual bypassing?

Conscience has been captured by guilt. The moral sense, which once oriented the individual toward the good, now points only toward the guilty. Every action must be examined for complicity. Every choice must be interrogated for privilege. The conscience no longer guides; it prosecutes.

Will has been captured by achievement. The drive that once built cathedrals and crossed oceans now runs on a hamster wheel of self-improvement. The will has been turned inward, set to work on the self, producing nothing but more refined production of the self.

Reason has been captured by all three. Reason might analyze trauma—but analysis is intellectualization, a defense mechanism. Reason might question guilt—but questioning is fragility, denial, the very symptom of the disease. Reason might critique the achievement drive—but critique must be productive, must lead somewhere, must itself become a project.

What faculty remains? What ground can the prisoner stand on to see the prison?

VIII. The Exhaustion

And so we arrive at the grey faces.

They are depleted. Of course they are depleted—they have made depletion into a virtue. To be tired is to be working. To be burnt out is to be committed. To collapse is to care.

But they cannot rest. Rest would be privilege (guilt forbids it). Rest would be avoidance (trauma forbids it). Rest would be stopping (achievement forbids it).

So the exhaustion deepens. And as it deepens, it becomes further evidence of the righteousness of the cause. “I am destroyed by this work—therefore the work must be important. I am emptied by this struggle—therefore the struggle must be real.”

They have made their misery into their credential.

The suffering proves the seriousness. The burnout validates the commitment. The depression demonstrates the depth of engagement with the wound, the weight of the guilt, the intensity of the striving.

And here is what the priests of this religion will not tell their flock: the work never ends because it is designed never to end.

If trauma could be healed, the therapy industry would collapse. If racism could be overcome, the diversity apparatus would be redundant. If the self could be optimized, the self-improvement market would evaporate.

The structure requires permanence. The wound must never close. The guilt must never be paid. The optimization must never complete. Infinity is built into the architecture—not as bug, but as feature.

IX. The Exit

Is there one?

The body knows something the colonized mind has forgotten. The body does not believe in infinite projects. The body believes in limits. In hunger that demands food. In exhaustion that demands sleep. In collapse that demands cessation.

And so the body rebels. Depression—that great refusal of the organism to continue. Anxiety—the alarm system screaming that something is wrong. The body’s no in a system that has abolished no.

The priests fold even this into the system. “Your depression is trauma response.” “Your anxiety is internalized oppression.” “Your body is storing the score.” Even the organism’s desperate revolt becomes material for the project.

But perhaps—perhaps—the body’s no cannot be infinitely recuperated. Perhaps at some point the simple animal refusal to continue will override the colonized mind’s insistence that it must.

Or perhaps the exit is absurdity. At some point the demands become so contradictory, the confessions so elaborate, the genuflections so baroque, that the entire edifice becomes comic. And one cannot kneel before what one is laughing at.

Or perhaps the exit lies in counter-imitation. If desire spreads mimetically, then so might refusal. One person rests without guilt—and another sees it, and imitates. One person drops their wound-identity—and another notices, and follows. The cage was built by imitation; perhaps it can be dismantled the same way. Not by argument, which the system has immunized itself against, but by example. By modeling a different way of being. By becoming worthy of a different kind of imitation.

Or perhaps—and here is the dangerous thought—the exit is simply to stop. Not to overcome the guilt through more work, but to dismiss it. Not to heal the trauma through more processing, but to drop it. Not to complete the project, but to walk away.

This would require something almost unthinkable: the capacity to be finished. To say: I have suffered enough. I have confessed enough. I have worked enough. It is done.

The ancient wisdom knew what the moderns have forgotten: there is a time to cease. The Sabbath was not laziness; it was completion. The harvest ended; the feast began; the rest was taken—not as recovery for more work, but as an end in itself.

They have stolen your Sabbath. They have made rest into preparation. They have made completion into denial. They have made the very concept of enough into a symptom of disease.

X.

I leave you with this:

They have told you that your weariness is meaningful. That your burnout is noble. That your suffering is work.

But perhaps your exhaustion is simply exhaustion. Perhaps your body is telling you the truth. Perhaps the project that never ends is not a calling but a con.

Perhaps the first act of genuine rebellion is this: to rest without guilt. To stop without shame. To be, for a moment, finished.

And in that rest, in that stopping, in that completion—perhaps something else becomes possible.

Something the wheel cannot turn. Something the project cannot capture. Something the priests cannot interpret.

Life itself—unmanaged, unoptimized, unprocessed.

Just life.

That would be a beginning.

Thus spoke one who has watched the grey faces multiply.