We Can Capture Our Way Out

Published 2026-01-14The climate debate suffers from a failure of imagination about scale. Critics of carbon capture argue it cannot possibly scale to meet the challenge. Defeatists argue the problem is simply too large. Both are wrong.

This essay makes a simple claim: even the extreme scenario—capturing all 40 billion tonnes of annual CO₂ emissions while changing nothing else—is economically achievable. The money exists. We already spend it on less important things.

If the extreme is possible, everything easier than the extreme is also possible.

The Numbers

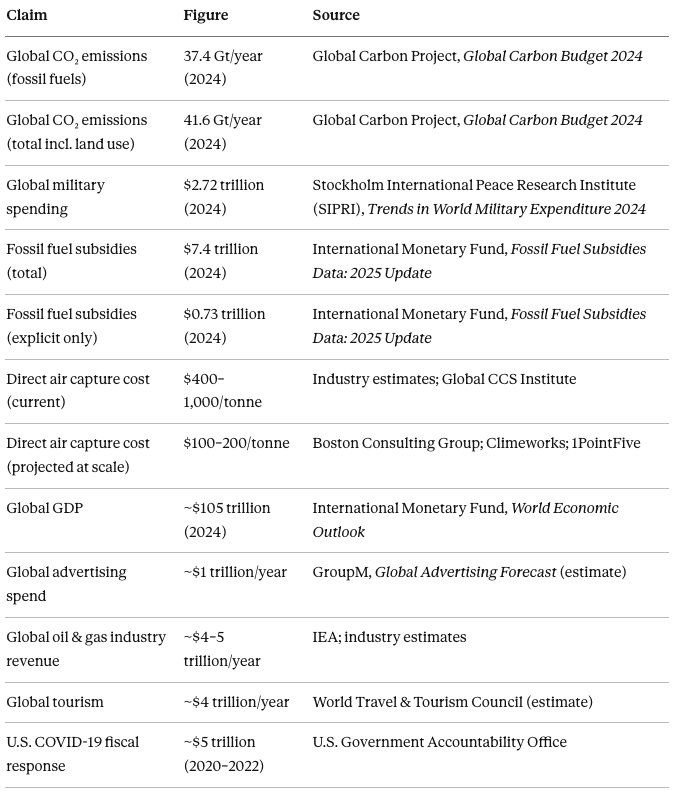

Global CO₂ emissions: ~40 gigatonnes per year

Current cost of direct air capture: $400–1,000 per tonne

Projected cost at scale: $100 per tonne

Cost to capture everything at $100/tonne: $4 trillion per year

Global GDP: ~$105 trillion

Share of GDP required: ~4%

Four percent of global economic output, annually, to completely neutralize all carbon emissions. That is the upper bound of what climate stability costs.

Is 4% of GDP Achievable?

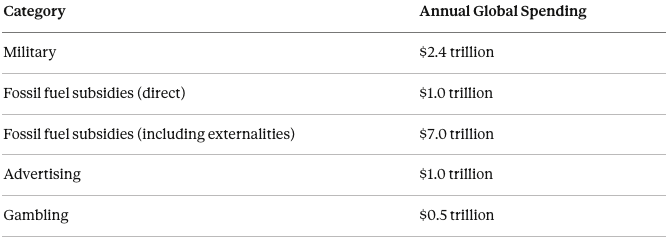

This is large. But consider what the world already spends each year:

The numbers speak for themselves.

We spend $2.4 trillion per year on militaries—much of it to secure access to the fossil fuels causing the problem.

We spend $1–7 trillion per year (depending on how you count) actively subsidizing the emissions we would need to capture.

We spend $1 trillion per year convincing people to buy things they don’t need.

The money for full-scale carbon capture is not hypothetical. It is currently being spent on other things. The question is not “can we afford this?” but “is this more valuable than what we’re currently buying?”

If the alternative is civilizational disruption, the answer is obviously yes.

Further Comparison

Other things that cost roughly $4 trillion:

-

The entire global oil and gas industry (~$4–5 trillion/year)

-

Global tourism (~$4 trillion/year)

-

COVID-19 fiscal response (~$5 trillion in the U.S. alone over 2–3 years)

We already operate industries at this scale. We have already mobilized resources at this scale in response to crisis. Four trillion dollars is not an abstraction—it is a quantity of economic activity we demonstrably know how to organize.

For further perspective: peak World War II mobilization consumed over 40% of GDP in major combatant nations. Four percent is an order of magnitude smaller than what societies have spent when they believed their existence was at stake.

The Free-Rider Problem Is Real—Until It Isn’t

There is a legitimate objection to the market-driven story: carbon capture is a public good. When you buy oil, you get something. When you buy capture, you help yourself and everyone else. Rational actors might sit on the sidelines, waiting for others to pay.

This is the classic free-rider problem, and it is real. But it is also solvable—and history shows how.

The Montreal Protocol Model

The 1987 Montreal Protocol phased out 99% of ozone-depleting CFCs within two decades. It is often cited as the most successful environmental treaty in history. But its success was not driven by altruism or international goodwill. It was driven by profit.

DuPont, which produced 25% of global CFCs, initially opposed any regulation. Then they developed alternative chemicals. Once DuPont had substitutes ready to sell, they flipped—becoming advocates for a global ban that would force competitors to buy their alternatives. The free-rider problem dissolved because “not destroying the ozone” became a product feature. You could sell “CFC-free” refrigerants at a premium.

The key insight: the free-rider problem disappears when public goods become private goods.

How This Happens for Carbon Capture

Several mechanisms are already converting atmospheric carbon removal from a public good into a private, tradeable asset:

Carbon credits: Companies buy capture and receive offsets they can sell or use to meet commitments. The voluntary market is still small (~$2 billion), but growing at 30%+ annually. As credit verification improves and corporate net-zero commitments bite, this market will expand.

Carbon border adjustments: The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism taxes imports based on embedded carbon. If this spreads—and there are strong incentives for it to spread—low-carbon production becomes a competitive advantage. Suddenly, capture is not charity; it is cost avoidance.

Government procurement: Just as defense contractors sell to governments, capture companies can sell removal directly to sovereigns. The U.S. 45Q tax credit already pays up to $180/tonne for direct air capture. Governments competing on climate credibility will bid up this market.

Mandates on emitters: Require power plants, cement factories, and refineries to capture a percentage of their emissions. This creates captive demand, just as renewable portfolio standards created demand for wind and solar.

Incumbent pivot: This is the DuPont play. Occidental Petroleum bought Carbon Engineering. Equinor, Shell, and TotalEnergies are building the Northern Lights storage network in Norway. If fossil fuel companies decide capture is their next business, they become lobbyists for carbon policy—not against it.

The Tipping Point

The free-rider problem dominates when capture is a cost center. It dissolves when capture becomes a profit center.

That transition can happen through policy (carbon prices, mandates, border adjustments) or through damage (climate costs rising until removal becomes cheaper than suffering). Either way, once a critical mass of capital sees capture as an opportunity rather than an expense, the political economy flips.

We have seen this before. DuPont went from opposing CFC regulation to advocating for it in under five years. The same rotation is beginning now, as oil majors acquire capture companies and Big Tech signs billion-dollar removal contracts.

The Market Will Accelerate the Transition

Once the tipping point is reached, the dynamics become self-reinforcing.

As climate damages mount—crop failures, coastal flooding, infrastructure destruction, supply chain disruption—the willingness to pay for atmospheric carbon removal increases. What seems expensive at $100/tonne becomes cheap compared to losing a coastline or a breadbasket.

Capital flows toward profit. Money moves. Industries form. Jobs appear. Political interests realign around the new economic reality.

The early signs are visible now: Microsoft, Google, and Stripe have committed billions to carbon removal purchases. Direct air capture costs have fallen from $1,000/tonne toward $100/tonne in under a decade. Oil majors are acquiring capture companies, hedging their future.

The same mechanism that created the fossil fuel economy—capital seeking returns—will create the capture economy. The difference is that this time, the profits come from removing carbon rather than emitting it.

Coordination through treaty requires political will. Coordination through markets requires only self-interest. The latter is more reliable.

The worse the crisis gets, the faster the capital rotates. The faster the capital rotates, the faster interests realign. The faster interests realign, the less coordination is required—because everyone is already moving in the same direction.

Why This Matters

Despair is the enemy.

When people believe climate change is unsolvable, they stop demanding solutions. They accept half-measures. They resign themselves to managed decline. Worse, they become vulnerable to dangerous proposals—untested geoengineering, authoritarian emergency powers, triage ethics that abandon entire regions.

The truth is simpler and more hopeful: the problem has a price tag, and we can afford it.

$4 trillion per year. Less than we spend subsidizing the problem. Less than we spend on global tourism. A fraction of what we have mobilized in past emergencies.

The extreme scenario—capture everything, change nothing else—is within our means. Everything less extreme than that is easier.

The bounds of the problem are known. The solution lies within them. And the market, once it sees the opportunity, will find its way there with or without international agreement.

We do not lack the resources to solve climate change. We do not even lack the coordination mechanism. We have capitalism, and capitalism follows profit. The only question is how much damage we sustain before the price signal becomes undeniable.

Appendix: Sources