Grammar as Alignment: The World Economic Forum

Published 2026-01-23

This essay extends the analysis in “The Language That Thinks For You.” Readers unfamiliar with grammar-as-alignment should read that essay first.

I. The Davos Puzzle

The World Economic Forum presents a puzzle. Its critics cast it as a shadowy cabal plotting global domination. Its defenders present it as a neutral platform for dialogue. Both miss something essential.

Watch the participants closely. They speak at length about “sustainability” without specifying implementations. They discuss “stakeholder capitalism” without naming antagonistic interests. They invoke “the Fourth Industrial Revolution” without identifying who drives it or who suffers from it. When pressed for specifics, there is nothing beneath the language — only more language.

And yet, ideas that originate at Davos reliably appear, years later, embedded in corporate reporting standards, government policies, and the common sense of educated professionals worldwide. ESG frameworks. Stakeholder capitalism. The Great Reset. These didn’t emerge from democratic deliberation or academic consensus. They emerged from Davos — and then became mandatory.

How? Not through explicit directives — the WEF issues none. Not through coercion — it commands no armies. Not even through persuasion in any conventional sense — the forum’s communications are notoriously vague.

The answer: the WEF functions as a grammar-generating institution. It produces distinctive ways of speaking that cascade through elite networks via mimicry, ultimately constraining what can be thought by determining what can be said.

This is the same mechanism described in “The Language That Thinks For You” — but operating at civilizational scale. Just as HR grammar makes “fire the incompetent employee” unsayable, WEF grammar makes “this serves elite interests at the expense of everyone else” unsayable. Just as therapy grammar forecloses moral accusation, WEF grammar forecloses questions about legitimacy and authorization.

II. The Grammar: 1973 and Now

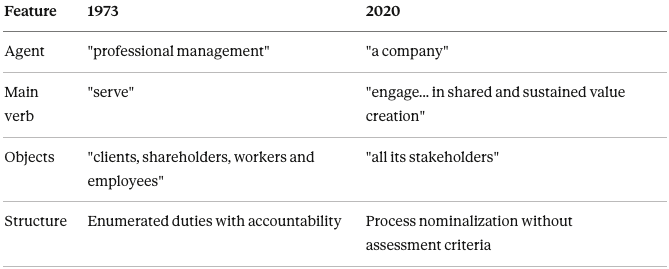

To see the grammar concretely, compare the 1973 Davos Manifesto with the 2020 Davos Manifesto.

The 1973 Baseline

The 1973 manifesto, subtitled “A Code of Ethics for Business Leaders,” opens:

“The purpose of professional management is to serve clients, shareholders, workers and employees, as well as societies, and to harmonize the different interests of the stakeholders.”

Note the grammatical features:

-

Concrete agent: “professional management” — specific people who can be held responsible

-

Active verb: “serve” — a concrete action that can be assessed

-

Enumerated objects: “clients, shareholders, workers and employees” — parties who can verify whether they’ve been served

The manifesto continues with operationalizable claims: “The management has to serve its clients. It has to satisfy its clients’ needs and give them the best value.” And: “The management has to serve its investors by providing a return on its investments, higher than the return on government bonds.”

Did management satisfy clients’ needs? Did returns exceed government bonds? You can argue about the answers, but the questions are well-formed.

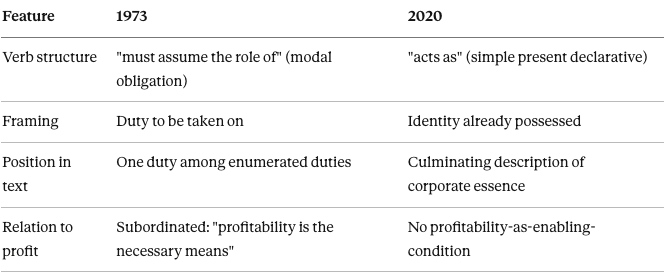

The 1973 manifesto also contains cosmic language: “It must assume the role of a trustee of the material universe for future generations.” But note the grammatical positioning: this is one duty among enumerated duties, subordinated to an accountability framework. The manifesto concludes: “profitability is the necessary means to enable the management to serve its clients, shareholders, employees and society.”

Stewardship is constrained by accountability. Profitability is an instrument. The company is a means to ends that can be specified and assessed.

The 2020 Grammar

The 2020 manifesto, subtitled “The Universal Purpose of a Company in the Fourth Industrial Revolution,” opens:

“The purpose of a company is to engage all its stakeholders in shared and sustained value creation. In creating such value, a company serves not only its shareholders, but all its stakeholders – employees, customers, suppliers, local communities and society at large.”

Compare:

“Professional management” (specific people) becomes “a company” (abstract entity). “Serve” (concrete action) becomes “engage... in shared and sustained value creation” (process nominalization). “Clients, shareholders, workers and employees” (parties who could verify service) becomes “all its stakeholders” (universal abstraction).

The 2020 manifesto continues: “A company is more than an economic unit generating wealth. It fulfills human and societal aspirations as part of the broader social system.”

What counts as fulfilling “human and societal aspirations”? How would we know if a company had failed? The grammar provides no criteria for assessment.

The manifesto reaches its apotheosis: “It acts as a steward of the environmental and material universe for future generations. It consciously protects our biosphere and champions a circular, shared and regenerative economy.”

Compare the similar 1973 language:

The 1973 grammar positions cosmic stewardship as an obligation within an accountability framework. The 2020 grammar positions stewardship as a constitutive identity — what the company is, not what it must assume.

This is the difference between “You must take on the role of a doctor” and “You are a healer.” The first can be contested on grounds of competence or appropriateness; the second is a declaration that resists falsification.

The Grammar’s Distinctive Features

Process Nominalization: Actions become things. “Management serves clients” becomes “engagement in shared and sustained value creation.” Agency is obscured. Assessment becomes impossible.

Agent Erasure: “We are witnessing profound shifts across all industries,” writes Klaus Schwab. Who is witnessing? Who causes the shifts? The passive construction and collective pronoun obscure these questions. Things simply happen; we merely witness them.

Stakeholder Proliferation: “All stakeholders have a responsibility to work together.” Responsibility shifts from corporations (who bear responsibility to stakeholders) to everyone equally. When everyone is responsible, no one is accountable.

Epochal Framing: Everything becomes a “revolution,” a “transformation,” a “paradigm shift.” The 2020 manifesto’s subtitle references “the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Opposition appears as denial of historical necessity. Specific policy debates dissolve into questions of “adapting to change.”

Identity-as-Cosmic-Actor: The company “acts as steward of the environmental and material universe.” This is not a claim that can be assessed but an identity that is declared. Accountability dissolves.

III. The Propagation Mechanism

How does a grammar that emerges among 3,000 Davos attendees come to constrain the thought of millions?

Stage 1: Genesis at the Apex

The WEF annual meeting functions as a grammar-generating institution. To speak well at Davos is to speak like a person who belongs at Davos — abstract nouns, passive constructions, epochal framings, stakeholder invocations. A participant who speaks in concrete terms, who names specific interests, who identifies winners and losers, reveals themselves as an outsider.

The grammar emerges through social selection. Variants that signal belonging proliferate; variants that mark outsider status are selected against. No one decides what the grammar should be; it evolves through status dynamics.

Stage 2: Codification by Intermediaries

The grammar moves from informal discourse to formal codification through consulting firms, accounting firms, standard-setting bodies, business schools, policy institutes.

The Big Four’s ESG framework exemplifies this. In September 2020, Deloitte, EY, KPMG, and PwC collaborated with the WEF to release standardized ESG reporting metrics. What was informal discourse became formal requirement. What was a way of speaking became a way of reporting, measuring, and auditing.

The ESG metrics are “organized under four pillars: Principles of Governance, Planet, People and Prosperity.” Note the alliterative abstraction, the replacement of concrete obligations with “pillars” and “principles.”

Stage 3: Adoption by Corporations

Corporations adopt the codified grammar for compliance, capital access, legitimacy, and status signaling. IR professionals, communications teams, sustainability officers — all must learn to speak the grammar fluently. They attend conferences, read trade publications, hire consultants, and imitate successful peers.

Stage 4: Media Amplification

Business media — Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, The Economist — play a crucial amplifying role. Journalists who cover Davos absorb its grammar. When they write about business, policy, or the economy, they reproduce the grammatical structures they have internalized.

Stage 5: Adoption by Aspirational Classes

The final stage reaches junior consultants, MBA students, NGO staff, policy analysts, academics. These populations are intensely attuned to status signals. By the time a young professional can speak the grammar fluently, they can no longer easily think outside it.

IV. What the Grammar Excludes

The power of a grammar lies in what it precludes.

National Interest: The grammar is post-national by construction. “Global challenges require global solutions.” “We must work together across borders.” National interest appears as parochialism or nationalism — a failure to see the big picture.

Class Conflict: The grammar dissolves class into “stakeholders.” Everyone is a stakeholder; interests are to be “harmonized” and “aligned.” The thought that some stakeholders systematically benefit at others’ expense cannot be formed.

Concrete Causation: Passive voice and agent deletion obscure who does what to whom. “Jobs are being displaced by automation.” “Communities are being left behind.” By whom? The grammar doesn’t say.

Limits and Refusals: The grammar has no vocabulary for “we should not do this.” Every problem has a solution; every challenge is an opportunity. The possibility that some transformations should be refused is grammatically inexpressible.

Legitimacy Questions: Who authorized the WEF to convene “stakeholders”? By what right do accounting firms set global standards? Within the grammar, convening is inherently legitimate. The question is ill-formed.

V. What the Grammar Includes

The grammar also has positive content — concepts it makes natural and prestigious.

Identity Over Class: Rich resources for gender, race, sexuality — but not class. “Diversity and inclusion” is well-formed; “class struggle” is not. Identity politics is compatible with global capital; class analysis is not.

Global Governance as Natural Scale: Multi-stakeholder initiatives, public-private partnerships, international frameworks. The grammar presupposes that governance naturally operates globally. National sovereignty appears as a legacy problem.

Technocratic Solutionism: Every problem has a technical solution. No resources for “this cannot be solved” or “this should not be solved” or “this is not ours to solve.”

Metrics and Measurement: ESG scores, sustainability metrics, impact measurement. What cannot be counted becomes invisible.

Innovation as Inherent Good: Disruption, transformation, revolution. Change is good; resistance is backwardness. The possibility that some innovations should be refused is grammatically difficult.

Expertise Over Democracy: “Experts agree.” “Research shows.” Legitimacy flows from credentials, not democratic mandate.

Partnership: Everything is partnership. Pfizer “partners” with Ghana. The World Bank “partners” with civil society. The grammar of collaboration obscures power differentials.

Resilience: Systems should absorb shocks and return to equilibrium. The grammar cannot express that some equilibria are unjust.

VI. The Self-Invisibility of Grammar

The mechanism produces a distinctive phenomenology: WEF participants genuinely do not experience themselves as exercising power.

They do not believe they are propagating a worldview because they do not experience themselves as speaking a particular grammar. They are just speaking, just thinking, just doing their jobs. That they speak in abstract nouns and passive constructions seems to them not a choice but a natural way of addressing natural problems.

This is why they laugh at conspiracy theories. In their experience, they are not coordinating. They attend panels. They participate in dialogues. They share perspectives. That the world increasingly conforms to patterns first articulated at Davos seems to them coincidence, or the natural progress of good ideas.

The test from “The Language That Thinks For You” applies here: confront a Davos participant with plain speech. Say: “This framework serves your class interests at the expense of working people. You’re using jargon to obscure what’s actually happening.”

They won’t agree and admit the game. They’ll be confused. They’ll think you don’t understand. “It’s more complex than that,” they’ll say. “We’re trying to balance multiple stakeholder interests. These frameworks help create shared value.” From inside the grammar, your accusation is not wrong — it’s unintelligible.

VII. Resistance and the Limits of Grammar

Grammatical Resistance

The most direct form of resistance is to speak a different grammar. This is what populist movements do. Donald Trump’s speech patterns — concrete, adversarial, nationally-bounded — represent a grammatical refusal. He names winners and losers. He identifies enemies. He speaks of “our country” and “our workers” in ways the WEF grammar cannot accommodate.

This explains the intensity of elite reaction to populist leaders — often disproportionate to policy differences. The threat is grammatical. By speaking differently, populists reveal that the WEF grammar is a grammar — contingent, contestable, serving particular interests.

The Limits of Grammatical Power

Grammar-as-alignment has limits:

It requires adoption. The grammar only constrains those who speak it. Religious traditionalists, ethnic nationalists, revolutionary socialists — these populations remain grammatically outside its reach.

It cannot compel. The grammar operates through status dynamics. Those indifferent to elite status, those outside professional hierarchies, are impervious to grammatical pressure.

It can be exposed. Though invisible to its speakers, the grammar can be made visible through analysis. Once people recognize they are speaking a particular grammar with particular exclusions, they regain capacity for reflection.

The Meta-Grammar Problem

But in what grammar does one expose a grammar? Any critique must be formulated in some language. The analyst who describes WEF grammar is not speaking from nowhere.

I do not resolve this difficulty. I note only that the self-reflexive challenge does not prevent local critical work. One need not possess a universal meta-grammar to observe that WEF grammar systematically excludes class analysis, national interest, and legitimacy questions. The observation has value even without a complete critical theory.

VIII. Conclusion

This essay has traced how a grammar emerges at the apex of global elite networks, cascades through institutional mimicry, and constrains the thought of millions who have never attended Davos.

The WEF case illustrates something general: power increasingly operates through grammar rather than ideology. You don’t need to convince people of propositions if you can control the linguistic structures within which propositions are formed. You don’t need to win arguments if you can determine which arguments are speakable.

This suggests both analytical and practical tasks. Analytically: study the grammars of power — their features, their exclusions, their propagation mechanisms. Practically: cultivate grammatical pluralism — maintain fluency in multiple grammars, preserve the capacity to think thoughts that professional languages foreclose.

The woman in the HR meeting who can only think in “development trajectories” has lost something. So has the Davos attendee who can only think in “stakeholder alignment” and “sustainable value creation.” They’ve lost the capacity to think certain thoughts — thoughts about power, about interests, about who benefits and who pays.

The first step toward recovery is noticing the bars.

Notes for Further Research

Empirical

-

Corpus linguistics analysis tracking grammatical features across WEF publications 1971-present

-

Comparative analysis of ESG reports before and after Big Four standardization

-

Interview studies with professionals who’ve internalized/resisted the grammar

-

Network analysis mapping grammatical propagation through institutional ties

Theoretical

-

Relationship to computational language: Are LLMs trained predominantly on WEF-grammar-saturated text?

-

The identity-class substitution: How did identity categories replace class categories?

-

Counter-grammars: What grammars successfully resist? Religious traditionalism? Ethnic nationalism?

-

Professional formation: How do MBA programs function as grammar-installation mechanisms?

For the foundational analysis of how grammar constrains thought, see: “The Language That Thinks For You: How Professional Grammar Shapes What You Can Think.”