The Invisible Right: On What Becomes Synonymous With Reality

Published 2026-02-09

I. The Asymmetry

There is an obvious asymmetry in how we perceive political colonization.

The left is easy to see. It operates as a program — with institutions, a lexicon, credentialing systems, and explicit goals. You can point at a DEI training seminar and say: that is ideology. You can hear the word “centering” deployed in a sentence and feel the machinery working. The left announces itself. It presents its revolution as a thesis, which means it can be identified, argued with, and refused.

The right is harder to see — not because it is subtle, but because it is total. It doesn’t ask for your assent. It doesn’t present itself as a thesis. It simply structures the conditions of your life until alternatives become unthinkable, and then it calls itself reality.

This is not a claim about conservative politicians or Republican policy platforms. The “right” I mean here is deeper than any party — it is the cluster of assumptions that govern how modern people relate to the world, to each other, and to themselves. And its most potent achievement is that most of us, even its critics, cannot see it as an ideology at all. We just call it “the way things are.”

II. The Concession: Markets Are Not the Problem

Before making the argument, a concession that is actually essential to it.

Markets are natural. They emerge spontaneously wherever humans gather at sufficient scale. They exist in some form in every documented civilization — Babylon, Greece, the Incan Empire, medieval Islam. Even animals engage in exchange behaviors. The anthropological record, despite Karl Polanyi’s ambitious claims in The Great Transformation, shows that market activity is “a deeply human phenomenon,” as recent comparative work on premodern economies has concluded. Polanyi was right that pre-modern markets were embedded in social, political, and religious institutions — but he overstated the case that markets played “a very minor role in human affairs.” They played a real role. They are part of what we are.

So the critique cannot be: markets bad, community good. That is a fantasy, and a politically useless one. The Athenian agora was a market. The medieval fair was a market. The bazaar, the souk, the Kula ring — all involved exchange, negotiation, price-discovery of some kind. Markets as tools — as mechanisms for allocating scarce goods among strangers at scale — are among humanity’s most successful inventions.

The question is: what happened to turn a tool into a theology?

Because something did happen. There is a difference — not of degree but of kind — between the Athenian merchant selling olive oil in the agora and the modern parent calculating the ROI on their child’s travel soccer team. The merchant was participating in a market that was embedded in a world of temples, civic obligations, household gods, and unchosen duties. The parent is living in a world where the market is the embedding context, and everything else — religion, community, family — is embedded in it.

The inversion is total. And it is invisible.

III. Polanyi’s Inversion

Karl Polanyi called this “the great transformation,” and his central insight remains devastating even where his historical details are contested.

In all prior human societies, Polanyi argued, “man’s economy, as a rule, is submerged in his social relationships.” People produced, exchanged, and consumed within webs of kinship, religion, and obligation that gave economic activity its meaning and its limits. The economy was embedded in society.

The great transformation reversed this. Through industrialization, enclosure, and the ideology of the self-regulating market, society became embedded in the economy. Economic logic — price signals, cost-benefit analysis, efficiency metrics — ceased to be one language among many and became the master language, the grammar within which all other claims had to be made.

This is the crucial distinction. Ancient markets existed within societies that had independent sources of meaning — temples, mysteries, tribal obligations, household gods. The market was a place you went, not a logic you inhabited. You could leave the agora and return to a world structured by entirely different principles.

Modern market society admits no such exit. There is no agora to leave. The logic of the market is the logic of the world. When every human interaction — education, healthcare, childcare, friendship, spiritual practice — must justify itself in cost-benefit terms, the market is no longer a tool. It is an ontology. It defines what counts as real.

Polanyi saw this clearly: “The idea of a self-adjusting market implied a stark utopia. Such an institution could not exist for any length of time without annihilating the human and natural substance of society.” The utopia he described was not a dream of paradise. It was a dream of totality — a single logic governing all human affairs. That dream has largely been realized, which is why we no longer experience it as a dream. We experience it as Tuesday.

IV. Heidegger’s Deeper Cut: Enframing

But Polanyi’s analysis, powerful as it is, still frames the problem as economic — as something markets did to society. There is a deeper analysis, one that identifies the root not in markets per se but in a transformation of how human beings disclose the world to themselves.

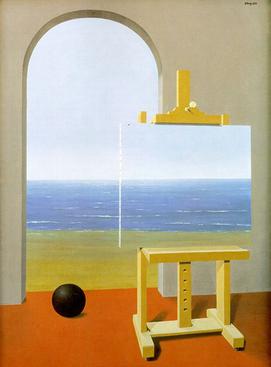

This is Heidegger’s concept of Gestell — “enframing” — and it may be the most precise name for the invisible ideology we are trying to identify.

In his 1953 lecture “The Question Concerning Technology,” Heidegger argued that the essence of modern technology is not any particular machine or process. It is a way of revealing — a mode of perception that transforms everything it encounters into Bestand, “standing reserve.” Under enframing, a river is not a river; it is a potential hydroelectric resource. A forest is not a forest; it is a timber supply. A person is not a person; they are human capital.

Heidegger’s crucial move was to insist that this is not itself technological. You don’t need a computer to think in terms of standing reserve. Enframing is a disposition toward reality — a way of seeing that precedes and enables any particular technology. It is the frame within which modern technology becomes possible and intelligible. And “when Gestell holds sway,” Heidegger warned, “it drives out every other possibility of revealing.”

This is the deeper version of the claim that the right colonizes by becoming synonymous with reality. Enframing doesn’t argue that everything should be treated as a resource to be optimized. It simply reveals everything as a resource to be optimized, and then the argument seems superfluous. Of course your child’s education should maximize outcomes. Of course your time should be managed efficiently. Of course a forest should be evaluated by its productive capacity. What else would you do? How else would you even see it?

“Man comes to the point where he himself will have to be taken as standing-reserve,” Heidegger wrote. “Meanwhile, man, precisely as the one so threatened, exalts himself and postures as lord of the earth. In this way the illusion comes to prevail that everything man encounters exists only insofar as it is his construct.”

This passage describes our situation with uncomfortable precision. We have become standing reserve for our own systems — our attention harvested by platforms, our productivity tracked by algorithms, our worth measured by output — and we call this empowerment. We are resources who believe they are managers.

V. The Education Tell

Nowhere is enframing more visible — once you know to look — than in education.

Consider “executive function.” This is the cluster of cognitive capacities — planning, prioritizing, impulse control, task-switching, working memory — that contemporary education has elevated to something like its highest developmental goal. Executive function is the telos of the modern curriculum. Children who exhibit strong executive function are praised. Children who don’t are diagnosed.

But what is executive function? Strip away the neuroscience terminology and it is the set of capacities required to be an effective worker in a market economy. Self-regulation. Deferred gratification. Task completion. Schedule management. The ability to suppress impulses that interfere with productivity. Executive function is the cognitive profile of a self-managing enterprise — a human unit optimized for the demands of standing reserve.

This is not a conspiracy theory. Nobody sat down and decided to redesign education to produce fungible labor units. That’s precisely the point. It happened without anyone deciding it, because enframing is not a decision. It is a way of seeing. Once you see children as developing (developing what? developing toward what?), the logic of optimization follows inevitably. You measure. You test. You intervene. You sort children into performance categories. You call it “evidence-based.” You don’t notice that the evidence base assumes a particular anthropology — one in which the human being is an information-processing system whose performance can be benchmarked.

What was squeezed out? Everything that cannot be measured: wonder, contemplation, purposeless play, the slow formation of character through unstructured encounter with the world. These aren’t “lost values.” They are modes of being that become unintelligible within the frame. You cannot make a case for wonder in cost-benefit terms. You cannot optimize for contemplation. So these human capacities don’t get argued against — they simply disappear from the curriculum as though they had never existed. The frame doesn’t reject them. It cannot see them.

This is the educational expression of Heidegger’s warning that enframing “threatens man with the possibility that it could be denied to him to enter into a more original revealing and hence to experience the call of a more primal truth.” The child who has been trained in executive function from age five has not been forbidden from wonder. She has simply never been shown that wonder is a real thing. Her world has been revealed to her entirely as standing reserve — as problems to be solved, tasks to be completed, outcomes to be achieved — and she has no reason to suspect that another mode of revelation exists.

She would call this reality. It is the only reality she has ever been shown.

VI. Liquid Modernity: The Market’s Dream of Itself

Zygmunt Bauman gave us another name for the world enframing produces: liquid modernity. The dissolution of all stable forms — permanent bonds, unchosen obligations, fixed communities, given identities — into fluid, renegotiable, market-mediated arrangements.

It is tempting to treat liquid modernity as a natural disaster, like a flood. Things just got more fluid. But liquidity is not an accident. It is what a market wants. From the market’s perspective, every fixed form is a friction. A stable community is a friction — its members have loyalties that compete with market signals. A permanent bond is a friction — it constrains the individual’s ability to optimize. An unchosen obligation is a friction — it allocates resources by tradition rather than by price. A religious commitment is a friction — it introduces non-economic criteria into decision-making.

Liquid modernity is the market achieving its final form: a world in which nothing is fixed, nothing is given, everything is renegotiable, and the sovereign individual moves through life as a consumer of experiences, relationships, and identities — selecting, discarding, and upgrading in perpetual motion.

This is why “everything solid melts into air.” Not because of some unstoppable historical force, but because solidity is an obstacle to market logic, and market logic has become the only logic. The family, the parish, the neighborhood, the guild, the craft tradition — all of these were solid. They resisted the market’s demand for total liquidity. And one by one, they dissolved. Not because they were argued against, but because the conditions that sustained them were systematically eroded by the same market logic that then sold back inferior, commodified substitutes.

You don’t have a parish. You have a “community” you selected on Meetup. You don’t have a neighborhood. You have a zip code where you purchased a residence. You don’t have a craft tradition. You have a “skill set” you “leverage” for “career development.” The language itself has been colonized. We lack the vocabulary to describe what we’ve lost because the vocabulary we now possess was designed by the system that took it.

VII. The Calvinist Root: Capital as the Final God

If enframing describes how the invisible right operates, we still need to ask where it came from. How did Western civilization arrive at a mode of perception that treats everything — including human beings — as standing reserve?

Max Weber’s argument in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) provides one essential thread. Weber traced the psychological origins of modern capitalism to an unexpected source: the Calvinist doctrine of predestination.

Calvin taught that God had predetermined, before the foundation of the world, who would be saved and who would be damned — and that nothing a person did in this life could alter that decree. The psychological consequence was unbearable anxiety. If you cannot earn salvation through works, and you cannot know whether you are among the elect, how do you live?

Weber’s answer: Calvinists began to interpret worldly success as a sign of election. If God had chosen you, He would bless your endeavors. Prosperity became evidence of grace. And because Calvinist asceticism forbade spending that prosperity on pleasure, the only sanctioned use of wealth was reinvestment — the continual accumulation of capital as an end in itself, understood as obedience to God’s calling.

“Man is dominated by the making of money, by acquisition as the ultimate purpose of his life,” Weber wrote. “Economic acquisition is no longer subordinated to man as the means for the satisfaction of his material needs.” Capital accumulation, once a means to an end, became the end itself — morally sanctioned by theology.

This is the moment — or at least the crystallization of a long process — when capital becomes the final god. Not merely a useful tool, not merely a measure of efficiency, but the sign of divine favor, the metric by which a life is judged. The Calvinist may have consciously rejected idolatry, but he built the greatest idol in human history: the self-regulating market as the arbiter of human worth.

Weber himself saw that the religious scaffolding eventually fell away, leaving only the logic it had generated: “The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so.” The theology withered. The spirit it produced — the relentless, rationalized pursuit of accumulation as an intrinsic good — did not. It became what Weber famously called the “iron cage” (stahlhartes Gehäuse) — a structure of rationalized economic life that no longer needs any religious justification because it has become the structure of reality itself.

This is the Calvinist contribution to the invisible right: not merely an economic system, but a soteriological displacement in which the soul’s destination is read from the balance sheet. The prosperity gospel that fills American megachurches today is not a modern aberration. It is the direct descendant of this displacement — the final, crude expression of a theological error that has been baked into Western capitalism for five hundred years. Joel Osteen is John Calvin’s idiot grandson, but the family resemblance is unmistakable.

VIII. The Trinity of the Invisible Right

We can now name the three faces of the invisible right more precisely:

Enframing (Gestell): The technological disposition that reveals everything as standing reserve — as resource to be optimized. This is the mode of perception. It does not argue; it shows. It does not command; it reveals. And because it constitutes the frame within which modern life is perceived, it cannot itself be perceived as a frame. It is invisible in the way that a pair of glasses is invisible to the person wearing them.

Capital as telos: The Calvinist-descended conviction, now entirely secularized, that the accumulation of wealth is not merely useful but good — that the maximization of returns is a moral imperative indistinguishable from the maximization of human flourishing. This is the theology of the invisible right, surviving long after the God who originally warranted it has been dismissed. It is the ghost of Calvinism haunting a secular world.

Liquefaction: The systematic dissolution of all non-market forms of human organization — family, parish, neighborhood, guild, tradition — which, from the market’s perspective, are frictions to be overcome. This is the politics of the invisible right, achieved not through legislation (though legislation helps) but through the relentless erosion of the material conditions that made non-market life possible. You cannot sustain a parish if no one lives near each other. You cannot sustain a neighborhood if everyone commutes ninety minutes. You cannot sustain a tradition if every generation is told that the highest good is to choose for yourself.

These three operate as a kind of unholy trinity: enframing provides the perception, capital provides the purpose, and liquefaction provides the political economy. Together they constitute an ideology so complete that it has ceased to appear as an ideology at all. It has become, simply, the world.

IX. “Just the Way Things Are”

There is a test for the completeness of an ideology’s victory: when the people most critical of it still cannot see it as an ideology.

You can write a devastating critique of progressive identity politics and file it under “critique of the left.” You can write a devastating critique of education-as-executive-function-training and file it under “the way things are.” You can see the first as a political project and the second as a description of reality.

That’s the colonization working perfectly. You have antibodies to the left because the left presents itself as a thesis. You have no antibodies to the right because the right presents itself as the world. The left tells you what to think. The right makes it impossible to think otherwise — not by forbidding other thoughts, but by structuring the conditions of life so that other thoughts have no purchase, no institutional support, no material basis.

Try to articulate why a child should spend an afternoon doing nothing. You will reach for words like “creativity” or “mental health” — market-adjacent concepts that translate unstructured time into an investment in future productivity. You cannot say what you actually mean, which is something closer to: a child should be idle sometimes because childhood is not a production process and a human being is not a resource. That sentence is true, but it is literally unintelligible within the frame. It sounds like sentimentality, or worse, like laziness. The frame has already determined what counts as a real argument, and “the child is not a resource” is not one.

This is what it means for an ideology to become synonymous with reality. It doesn’t censor. It doesn’t argue. It simply constitutes the field of the intelligible, so that certain truths cannot be spoken — not because they are forbidden, but because the language in which they could be spoken has been quietly removed from circulation.

X. Where But Not Yet When

Heidegger was wrong about many things. He was catastrophically wrong about the political implications of his own thought. But he was right about this: the danger of enframing is not that it gives us wrong answers. The danger is that it forecloses the questions. It threatens us “with the possibility that it could be denied to [us] to enter into a more original revealing.”

The invisible right has succeeded not in making us believe false things, but in making certain true things unthinkable. That a child is not an investment. That a river is not a resource. That a neighborhood is not a market. That the purpose of a human life cannot be expressed in the language of optimization. That there are forms of value that price cannot capture and that the attempt to capture them in price destroys them.

These are not sentimental claims. They are ontological ones. And they are precisely the claims that the invisible right, by becoming synonymous with reality, has placed beyond the reach of argument — not because they have been refuted, but because the frame within which they would need to be articulated has been replaced by a frame in which they register only as noise.

The left colonizes the soul by giving it a bad religion. The right colonizes the soul by making religion — by which I mean any orientation toward the transcendent, the gratuitous, the non-instrumental — seem like a category error.

One is a heresy. The other is an apostasy so complete that the apostate does not know he has left the faith.

We know where we are. We are inside the frame. The question — Heidegger’s question, and ours — is whether it is possible to see the frame as a frame while still standing inside it. Whether the glasses can, even for a moment, become visible to the one who wears them.

Heidegger thought the saving power might emerge from art, from poiesis — the mode of making that brings forth rather than challenges forth. Others have placed their hope in contemplative traditions, in liturgical life, in the stubborn persistence of communities that refuse to liquefy. I don’t know the answer. But I am increasingly certain that the question — how do you resist an ideology that has become synonymous with the world? — is the only political question that matters. And it is a question that neither left nor right, as conventionally understood, is equipped to ask.

Sources

-

Martin Heidegger, “The Question Concerning Technology” (1954) — the primary text on Gestell and standing reserve

-

Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time (1944) — on the disembedding of economy from society

-

Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) — on the Calvinist roots of capital accumulation as moral imperative

-

Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Modernity (2000) — on the dissolution of stable social forms

-

Robert Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (2000) — on the empirical collapse of American civic life

-

Peter Gray, “The Decline of Play and the Rise of Psychopathology in Children and Adolescents,” American Journal of Play (2011) — on the consequences of structuring childhood as production

-

Iain Thomson, Heidegger, Art, and Postmodernity (2011) — on enframing as the ontotheology of our age, including its educational implications