The Gaze

Published 2026-02-11

Every generation builds a self to survive the judgment that destroyed the last one.

This is the hidden engine of the last eighty years of Western identity: not progress, not liberation, not even decline — but fear. Specifically, the fear of being seen. Each generation watches its parents get exposed as frauds or fools or failures, and it builds a new self — an architecture of identity designed to be immune to the specific accusation that took the last generation down.

The result is not evolution. It’s an arms race. And like all arms races, it produces ever more sophisticated defenses that solve the last problem while creating the next one — until you arrive at a generation that has defended itself so completely against the gaze of the other that it can no longer be reached by anything at all.

I. The Given Self (Pre-Boomer)

Before the arms race, there was no arms race. There was just the water.

The pre-Boomer self — the self of the Greatest Generation and everything before it — was not chosen. It was received. You were your family, your town, your trade, your congregation. Identity was not a project. It was an inheritance, like the farm or the family Bible, and you no more chose your self than you chose your face.

This self had a thousand problems. It was rigid. It was provincial. It was suffocating for anyone who didn’t fit — for women, for minorities, for anyone whose inner life exceeded the container they were born into. The small town that knew your name also knew your business, and the knowing was a leash. The congregation that held you also watched you, and the watching had teeth.

But the given self had one quality that everything after it lacks: it was unselfconscious. The man who was a farmer was a farmer the way a stone is a stone. He didn’t perform farmer. He didn’t curate farmer. He didn’t worry about whether farmer was the optimal use of his potential. The role and the man were the same thing, and the sameness — however limiting — meant there was no gap between the self and its expression. No glass. No echo. No audience.

The judgment of others was real and constant but it operated within a shared framework. Everyone was being watched, but everyone was being watched by the same God, according to the same rules. The gaze was omnipresent but it was legible. You knew what you were being judged for. You knew what good looked like. The anxiety was about failing to meet a standard, not about whether the standard existed.

This is the self that every subsequent generation has been running from. And the running begins with the Boomers, who looked at the given self and saw a cage.

II. The Expressive Self (Boomers)

The Boomers were the first generation to choose a self. This is the hinge. Everything that follows — the entire genealogy of fear — starts here, with a generation that looked at its parents’ lives and said: There must be more than this.

The accusation they leveled at the given self was: You are trapped. You are conformist. You are living someone else’s life. The gray flannel suit, the silent father, the dutiful mother, the church pew and the country club — these were not identities but prisons. The Boomer project was liberation: find your authentic self beneath the roles. Self-actualization. Self-expression. Self-discovery. The word self appears three times in that list, and the repetition is the point. The self became a destination.

And the project was sincere. Radically, almost painfully sincere. The Boomers protested, experimented, dropped out, tuned in. They did acid and read Alan Watts and went to Esalen and believed — truly believed — that if they could strip away the inherited roles, the authentic person underneath would emerge like a statue from marble.

The fear driving this was the fear of being trapped — of living and dying inside a script someone else wrote. Of getting to the end and realizing you never lived at all. It was a valid fear. The given self was a cage for many people. Breaking out was, for many, a genuine act of courage.

But the Boomer rebellion contained its own poison, and the poison was this: you cannot build a self on the rejection of the given without making the self a project. The moment identity becomes something you discover, excavate, express — the moment it stops being water and becomes a quest — you’ve introduced a gap between the self and its expression. You’ve turned the self into a performance, even if the performance is called “authenticity.”

The Boomers didn’t see this. They thought they were breaking free. What they were actually doing was building the first self that existed for an audience — even if the audience was just the mirror. The expressive self says: Look at who I really am. And the “look at” is already the seed of everything that comes next.

Because here’s what happened: the Boomer who did acid in 1968 got an MBA in 1978 and managed a hedge fund in 1988. The one who protested Vietnam sent his kids to private school. The one who preached free love got a prenup. The authentic self, it turned out, was remarkably compatible with careerism, consumerism, and all the other -isms it was supposed to transcend.

And their children were watching.

III. The Disengaged Self (Gen X)

Gen X watched their parents’ sincerity reveal itself as theater. The authentic self was just the conformist self in a dashiki. The liberation was just a costume change. Mom and Dad preached self-expression and then got divorced. They valorized authenticity and then sold out. They tuned in, turned on, dropped out, and then went back to the office and stayed for thirty years.

The accusation Gen X leveled at the Boomers was: You are hypocrites. Not small hypocrites — not people who failed to live up to their ideals. Structural hypocrites. People whose ideals were themselves a performance, a self-congratulatory story about liberation that masked the same appetites and ambitions that drove every generation before them. The Boomers said find yourself. Gen X looked and found nothing — or worse, found the same compromised, self-interested animal that was always there, just wearing tie-dye instead of a tie.

The fear driving Gen X was the fear of being duped by your own earnestness. Of investing sincerely in something — a cause, a relationship, a project of self-discovery — only to have it revealed as hollow. Better not to invest. Better not to try. Better to opt out, to shrug, to say whatever and mean it. Kurt Cobain didn’t refuse to be a rock star because he was modest. He refused because becoming a rock star meant becoming the thing he despised — a person who cared, publicly, about something — and the caring was the trap.

The Gen X self is the disengaged self. Not ironic yet — irony requires energy, requires a stance. The disengaged self doesn’t have a stance. It has an absence. The slacker, the dropout, the person who won’t play because playing means losing and losing means being seen as the fool your parents were.

This was, in its way, an honest response. Gen X correctly identified the Boomer problem: sincerity without structure becomes performance. But the solution — withdrawal — created a vacuum. If you don’t build a self, you don’t get an alternative. You get a void. And voids get filled.

What Gen X produced culturally was extraordinary — the best movies, the best music, the best comedy of the late twentieth century came from people who’d given up on meaning and discovered that the giving-up was its own kind of freedom. But what Gen X produced personally was a generation of absent fathers and disengaged mothers and people who were cooler than everyone in the room and also, somehow, not fully in the room.

And their children were watching.

IV. The Optimized Self (Millennials)

Millennials were raised by two messages that contradict each other so completely that the only rational response was to build a system.

Message one, from their Boomer parents: You are special. You can be anything. Follow your passion. The authentic self is in there, you just have to find it.

Message two, from the Gen X cultural atmosphere: Nothing matters. Everything is a performance. Don’t be a sucker.

The Millennial synthesis was: Make it matter through effort. If nothing is given and nothing is found, then the self must be built. Engineered. Optimized. The Millennial doesn’t inherit an identity or discover one. The Millennial constructs one, brick by brick, habit by habit, metric by metric.

The fear driving this generation was the fear of falling behind — of being the one who didn’t do the work, didn’t build the system, didn’t invest in themselves while everyone else was compounding. But underneath that fear was a deeper one, inherited from both parents: what if there’s nothing underneath? The Boomers said the authentic self was there if you dug deep enough. Gen X said the digging was pointless. The Millennial response was to make the digging irrelevant by building something on top — a self so polished, so optimized, so thoroughly engineered that the question of what’s underneath never needs to be answered.

This is the self of morning routines and personal brands and quantified everything. The self of Atomic Habits and cold showers and gratitude journals and continuous glucose monitors. It’s a self that is, by any external measure, more disciplined, more productive, more health-conscious than any self that preceded it. It is also, by any internal measure, exhausted — because the optimization never ends. There’s always another book, another protocol, another marginal gain. The project of the self becomes the self’s full-time occupation, and the occupation leaves no room for the occupant.

The specific judgment the Millennial fears is being insufficient. Not trapped (Boomer fear), not a hypocrite (Gen X fear), but simply not enough. Not productive enough, not mindful enough, not optimized enough. The gap between the current self and the ideal self is the Millennial’s permanent address. They live in the gap. They furnish the gap. They turn the gap into a lifestyle brand.

And the cruelest feature of the optimized self is that it produces a person who can describe their own prison with perfect clarity. The Millennial knows the optimization is a trap. They’ve read the articles. They’ve done the therapy. They can give you a TED talk about the hedonic treadmill and the problems with productivity culture while standing on the treadmill, optimizing the talk. The knowledge doesn’t free them because the knowledge is just another input. It gets absorbed into the system and converted into a better system.

And their children — and younger siblings — were watching.

V. The Ironic Self (Gen Z)

Gen Z watched the Millennials optimize and saw that it didn’t work.

Not that it failed to produce results — it produced extraordinary results. The résumés, the bodies, the morning routines, the carefully curated lives. But the results didn’t produce the thing the results were supposed to produce. The optimized Millennials were not, on the whole, happy. They were anxious. They were medicated. They were performing wellness while being profoundly unwell. The system worked and the person inside the system was dying.

The accusation Gen Z leveled was: You are trying so hard and it’s not working and watching you try is painful. The word for this is cringe. Cringe is not a casual insult. It’s a generation’s entire epistemology compressed into a single syllable. Cringe is what happens when sincerity is attempted without ironic cover. When someone is caught caring — earnestly, visibly, without a safety net. The Millennial who posts an unironic gratitude list. The LinkedIn influencer sharing their “journey.” The wellness guru who seems to believe their own content. Cringe. All of it, cringe.

The fear driving Gen Z is the fear of being sincere about something that turns out to be fake. Of investing yourself in something — a career, a cause, a relationship, a self-improvement project — only to have it revealed as cope, as performance, as just another product. The Boomers feared the cage. Gen X feared the hypocrisy. Millennials feared the insufficiency. Gen Z fears the cringe — which is to say, they fear being caught wanting something genuinely in a world where every genuine want is immediately available for public dissection.

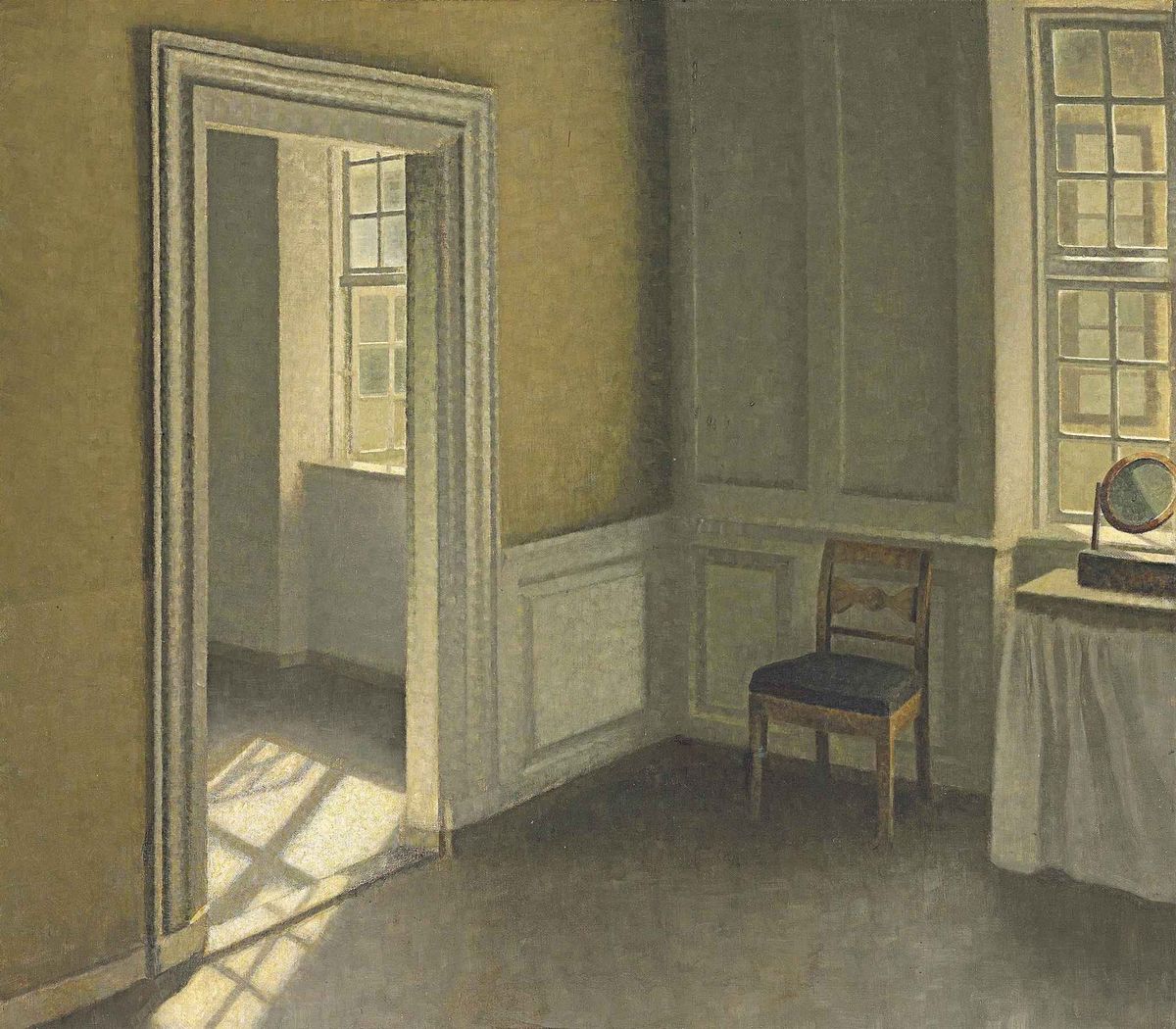

The solution is the ironic self. You still do the thing — you still post, still try, still want — but you do it in quotation marks. Every vulnerable statement comes with an escape hatch: the “haha” after the confession, the self-deprecating caption under the earnest photo, the I know this is dumb but before the thing that isn’t dumb at all. The ironic self is a glass enclosure that allows the person inside to see out but prevents anything from getting in.

Looksmaxxing is the paradigmatic Gen Z practice — not because it’s about looks but because of its structure. It borrows every tool from the Millennial optimizer (the routines, the tracking, the quantification) but wraps them in an ironic frame. I know this is cope. I know this won’t fix anything. I’m doing it anyway. It’s optimization after hope. Self-improvement as a bit. The gesture toward a better self, performed for an audience, with the full understanding that the audience and the performer are both in on the joke and the joke is that none of this will save you.

The ironic self is the most sophisticated defense mechanism a culture has ever produced. It is almost perfectly invulnerable. You can’t accuse it of being trapped (it knows). You can’t accuse it of hypocrisy (it already said so). You can’t accuse it of trying too hard (it was joking). You can’t accuse it of not trying (it was also not joking). The defense covers every angle. The glass is seamless.

And inside the glass, a person is slowly suffocating.

Because irony is not a stance. It’s a solvent. It dissolves everything it touches — including, eventually, the person doing the dissolving. The ironic self cannot want anything without pre-emptively disowning the wanting. It cannot love without performing love. It cannot grieve without packaging grief as content. Every experience is immediately translated into a form that can survive public scrutiny, and the translation strips out the thing that made the experience an experience.

Gen Z knows this. They know the glass is there. They call it being chronically online or being irony-poisoned and the naming is accurate and the naming changes nothing because the naming is itself ironic, another layer of glass on top of the glass.

And the children — their younger siblings, the next wave — are watching.

VI. The Dissolved Self (Gen Alpha)

Gen Alpha is the first generation born entirely inside the glass. They didn’t build it. They didn’t choose it. They inherited it the way the pre-Boomers inherited the farm — as the given, the water, the air they breathe.

They are also the first generation for whom the irony-sincerity distinction has collapsed. Not because they’ve transcended it but because they’ve never known anything else. Their humor is meta-ironic: jokes about jokes about jokes, layered so deep that the question “are you serious?” becomes literally unanswerable. Not because they’re being evasive but because the categories of serious and not-serious no longer function. When a twelve-year-old says “skibidi toilet,” they are not being ironic and they are not being sincere. They are being something for which we don’t have a word yet — something that exists in the space where irony and sincerity have merged into a single, undifferentiated signal.

And yet — and this is the genuinely interesting data point — Gen Alpha’s social hierarchies are organized around authenticity. The worst thing you can be called on a Gen Alpha playground is fake. The worst thing you can do is perform specialness. “Pick me” is an accusation of inauthenticity. “No cap” is an oath of sincerity. The vocabulary is saturated with the demand for realness: real, valid, BFFR, no cap.

This is a generation that cannot access sincerity in its communication but demands authenticity in its social world. That can’t stop performing but punishes anyone caught performing. That has never known a self without an audience but craves, in some inarticulate way, a self that doesn’t need one.

The fear — if it’s a fear, if the word still applies — is harder to name. Gen Alpha isn’t afraid of the cage (Boomers), or of hypocrisy (Gen X), or of insufficiency (Millennials), or even of cringe (Gen Z). Gen Alpha is afraid of something more fundamental: that there’s no there there. That the self is nothing but performance, all the way down. That if you stripped away the layers — the irony, the memes, the aesthetic, the curated feed — you wouldn’t find a person underneath. You’d find another layer. And another. And then nothing.

This isn’t nihilism. Nihilism is a position, and positions require a self to hold them. This is something prior to nihilism: the suspicion that the self itself is a meme. That identity is content. That you are a thing the algorithm assembled from inputs and there’s no ghost in the machine, there never was, and the demand for authenticity that structures your entire social world is itself a performance, the biggest and most desperate performance of all.

The early signals are ambiguous. They’re posting less. They prefer cinema to streaming — the embodied, the shared, the physically present. They’re cautious online in ways Gen Z wasn’t. They’re pulling back from the panopticon, not because they’ve been told to but because they’re tired, a tiredness so deep it might be better called instinct — the animal sense that something in the environment is making them sick.

Whether this tiredness becomes a foundation or just a different flavor of withdrawal is the open question. The arms race has been running for eighty years. Each generation’s defense became the next generation’s disease. Each new self was built to survive the gaze that destroyed the last one, and each new self was destroyed by a gaze it didn’t anticipate.

Gen Alpha is the first generation that might not build a new self at all. Not because they’ve chosen not to. Because they might not be able to. The tools for self-construction — sincerity, irony, effort, withdrawal — have all been tried and all been found wanting and they know this before they’re old enough to drive.

What comes after the last defense fails?

VII. The Gaze Beneath the Gaze

Here is the thing that every generation in this genealogy has been running from, the thing that each new self was built to deflect, the thing that remains when the arms race exhausts itself:

You can be seen.

Not your performance. Not your optimization. Not your irony, your brand, your aesthetic, your curated self. You. The small, needful, easily hurt thing that wants to love and be loved and is terrified that what it is — without the defenses, without the layers, without the glass — is not enough.

The pre-Boomer self didn’t have this problem because the self was given and the gaze was shared. Everyone was seen by the same God, in the same light, and the light was harsh but it was legible. You knew what you were.

Then the Boomers shattered the shared gaze and replaced it with the mirror, and every generation since has been trying to manage the consequences of that shattering. Not the liberation — the liberation was real. The exposure. Because when you remove the shared framework, you don’t get freedom from judgment. You get judgment from everywhere, with no rules, no legibility, no way to know what you’re being measured against.

The Boomer built an expressive self to say: See the real me. But the real me was a performance.

Gen X built a disengaged self to say: I don’t care if you see me. But the not-caring was a performance.

The Millennial built an optimized self to say: See how much I’ve built. But the building was a performance.

Gen Z built an ironic self to say: I know you see me and I don’t take it seriously. But the not-taking-it-seriously was a performance.

And Gen Alpha, inheriting all of these defenses and none of their convictions, is left holding the question that was underneath all along: What if you let yourself be seen — without a strategy for how you’ll be received?

This is not a new question. It’s the oldest one. Every serious spiritual and philosophical tradition in human history has arrived at some version of it.

Meister Eckhart called it Gelassenheit — releasement, letting-be. The willingness to let the self empty out until what remains is the ground, which was always there, which needs no defense because it isn’t yours to defend.

The Desert Fathers called it kenosis — self-emptying. The radical vulnerability of a self that has stopped trying to manage its own image, because the image was never the point.

The Buddhists call it anatta — no-self. Not the destruction of the self but the recognition that what you’ve been defending was never a fixed thing in the first place. The glass was protecting nothing. There was nothing behind it but the open air.

Even Kierkegaard, who understood the fear of the gaze better than anyone, said the only exit was the leap — the willingness to be absurd, to be seen as a fool, to stand before the infinite without an ironic footnote.

None of these traditions are comfortable. None of them are optimized. None of them have an escape hatch. They all require the one thing the arms race was designed to prevent: encounter. Direct, unmediated, unperformed contact with another person, with the world, with whatever you want to call the ground beneath the ground.

The pre-Boomers had this, crudely, through the given structures of community and faith. It was coercive and limited and real. What’s been lost across the eighty-year arms race is not the structures — those needed to go — but the encounter. The willingness to stand in the open. To be seen without a costume. To say I love you without a “haha.” To need someone without calling it cringe. To be hurt and not package the hurt. To want and not ironize the wanting.

Every generation’s new self was a more sophisticated way of saying: Don’t look at me. Don’t really look. Look at this instead — and “this” was the role, or the expression, or the disengagement, or the system, or the irony, or the meme. Layer after layer, defense after defense, each one thinner and more transparent than the last, until you arrive at a fifteen-year-old who can’t tell if they’re joking and can’t tell if they’re serious and calls anyone who can tell fake.

The arms race doesn’t end by building a better self. It ends by stopping. By letting the gaze in. By discovering — and this is the terrifying, liberating thing that every tradition promises — that what the gaze finds, when it finally penetrates all the layers, is not the insufficient, cringe, hypocritical, trapped thing you were afraid of.

It’s just a person. Standing there. Blinking in the light.

And the light doesn’t destroy them. The light is what they were made of.